"Wanderer III" : A cruising yacht classic and the 96th degree of longitude

YACHT-Redaktion

· 02.09.2023

From Thies Matzen

Take: an old boat, a remote longitude in the Pacific, three couples. Add: a less connected and consumed world; letters and boats instead of bytes carrying messages around a more analogue world; plenty of salt. Set the temperature to an average of 25ºC; wait seventy years - and this story of "Wanderer III" at longitude 96ºW begins to reach deep back into a sailing era when readers still took time to read articles of the length of this one.

The boats, on the other hand, were rather short. By today's standards, it takes some imagination to picture the nine metres and twenty-seven of "Wanderer III" as a comfortable living space - but that's exactly what they have been to us for forty years. And nobody could have guessed in 1952, when she glided into her element at her launch in Burnham-on-Crouch, England, that she would one day be credited with an affinity for a Pacific longitude. And that seventy years later, in the midst of the great outdoors of the Falkland Islands, she would be waiting on a mooring specially laid for her and still be ready to sail to it again. Just like that - it would be the ninth time.

No other yacht has characterised the beginning of cruising sailing as much as this 30-foot wooden boat. Hardly any other yacht has travelled the world as far and wide as she has. She has been honoured twice with the prestigious Blue Water Medal, which has been awarded annually since 1922, for her voyages, which have shaped the sailing of an entire era. First in 1955 with the British sailing couple Eric and Susan Hiscock and then in 2011 with us.

"Wanderer III" has a way of persuading the owners to sail around the world

Yet "Wanderer III" is by no means the best, fastest, most comfortable or even that elusive ideal cruising yacht. But there is something about her that has kept her three blue-water owners - Eric and Susan Hiscock, Gisel Ahlers with partner Chantal Jourdan and my wife Kicki and me - sailing her around the world almost continuously for seventy years.

Most read articles

In 2006, shortly before Kicki and I once again set our course for the high southern latitudes - where we have mainly sailed ever since - we crossed an ocean with "Wanderer III" that she has sailed since 1953 as if it were the most common thing in the world: the Eastern Pacific. We were travelling in the westerly wind belt towards Chile, but the aft wind was hardly noticeable. Instead of reeling off light-footed, downwind miles as if in a frenzy, an alternation of lulls and fronts made for an uncomfortable stop-and-go.

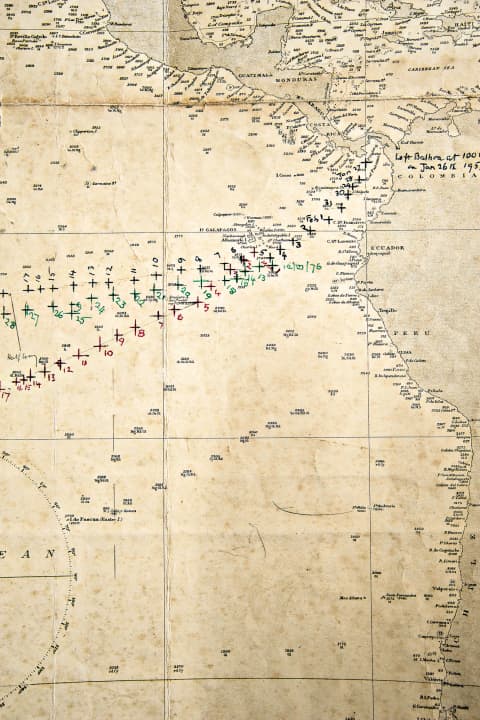

Below deck, I once again bent over the spread-out nautical chart from Gisel and Chantal's time. It had character; coffee stains created islands on it that were not islands. On an earlier voyage, I had added blank paper to enlarge the ocean that the map represented. A sextant elevation placed us in the shape of a small cross at 39º 24'S/95º 58'W; that was us, "Wanderer III" was right there.

At some point, I became aware of the many other noon altitude crosses scattered across the paper surface. My eyes travelled south and north along our longitude - we were only two minutes away from 96ºW. Its line stretched northwards towards Mexico, untouched by any landmass, where it was lost in continental inconspicuousness. Southwards, it ran unhindered through the centre of the Pacific, directly into one of the world's loneliest ocean areas as far as Antarctica. It was a landless loner. No question: anyone who crossed it was definitely on a long journey.

Blind date in the Pacific nowhere

I had just marked a sixth cross on it in pencil - next to one of Gisel's, five of ours - when I realised that two more would have to be added, namely those of Eric and Susan's two circumnavigations on "Wanderer III" in the fifties and sixties. It was at that precise moment that it really sank in: the eighth meeting of "Wanderer III" with this remote longitude in the Pacific nowhere had just taken place.

The pencil crosses represented nothing less than eight unique sea moments on it, spanning over half a century. What exactly had allowed "Wanderer III" to create them again and again? What exactly had enabled her to survive two reef strandings, a capsize, several knock-downs and countless storms over more than 300,000 nautical miles sailed?

On the 14th day of their first passage in the Pacific in 1953 - from Panama to the Marquesas on the trade wind route around the world - the perennial bananas in the forepeak were overripe. "Falling like leaves in autumn," Eric wrote almost poetically in the logbook on 8 February 1953. His notes are astonishingly informal, less formal, they do without many technical lists of quantifiable values on air pressure, wind and weather, but are narrative; in words instead of numbers, with a note of the daily midday position.

First Pacific passage for "Wanderer III" is a tough one

But at 4º 41'S/96º 08'W the poetry was over: "The movement is terrible. For breakfast, the cooker, complete with kettle and pot of boiling water, ripped itself off its gimbal. Threw away the last bananas." And shortly afterwards: "The movement is just too much."

After 1,482 of the 4,000 nautical mile passage, they had long passed the Galapagos Islands. The wind had increased steadily throughout the night and they were pushing westwards at six knots.

"I tried to make her self-steering with the main furled and the jib held back ... but she turns out not to be well-balanced and only holds her course for a few seconds in a beam reach. Giles should study the 'metacentric shelf'."

"Back to the drawing board, Giles," Eric seems to suggest to the boat designer of the "Wanderer III", Laurent Giles, about a year after her launch. This is almost heresy and not typical of Eric. But at this moment in the logbook entry, he doesn't seem to have been very cheerful.

"The sky is mostly overcast. This is not what I imagined the south-east trade wind to be like. A gloomy day. Before dinner we reef down to the second reef. Susan is very tired, and she had the first night watch but couldn't sleep, while I could barely stay awake on deck."

"Wanderer's" fast, jerky movements and the strain of constant hand steering with the resulting lack of sleep dominate the entries in the logbook. Wind steering systems did not yet exist. Sleep was rare in the under-manned blue water sailing of the fifties.

"Wanderer III" hardly seems suitable for the high latitudes for the Hiscocks

Downwind, her long keel and large lateral plan "Wanderer III" hold her course well, and two identical headsails, one on port and one on starboard, effortlessly stabilise the course downwind. However, I have never had to steer by hand for any length of time on long passages, as I still have the services of her first windvane to fall back on. It is one of the two prototypes that its inventor Blondie Hasler installed simultaneously on his famous folk boat "Jester" and on "Wanderer III" in the mid-sixties. It has logged more than 230,000 nautical miles to date, still with original parts. It is simple, has never caused any problems and still makes me believe that "Wanderer" is perfectly balanced.

At their first meeting with longitude 96º W, however, Eric and Susan clearly disagreed. It wasn't until well after halfway to Nuku Hiva that they were finally able to celebrate a perfect sailing day - on a Friday the 13th - on the forecastle with rum punch and tinned salted peanuts.

After her first circumnavigation, her owner Eric Hiscock mused: "'Wanderer III' is surely the smallest boat in which a level-headed person with genuine respect for the sea would want to cruise an ocean."

"Wanderer III" is a mirror of the times

The knowledge and mindset of the fifties characterised their design. Nobody knew exactly how small a boat could be to get it safely around the world; and how strong it had to be built. This was countered with larger dimensions in critical areas - in the bilge, the mast area - and with a myriad of stiffening bulkheads integrated with fore-and-aft guides. The British liked their yachts compartmentalised and not open.

The 9.27 metre long "Wanderer III" is only 2.56 metres wide - for the simple, almost ridiculous reason that the construction price of a yacht in 1952 was based on the Thames Tonnage used at the time; and this in turn weighted the width excessively, so narrow was synonymous with cheaper. Moreover, nobody questioned why a nine-tonne yacht should have to carry around three tonnes of lead for its entire life. But after "Wanderer's" first circumnavigation, Eric did just that. Under the impression of her sleep-killing lurching and rolling and the encounters with wider American yachts with a shallower draught, his preferences changed.

His "ideal yacht", he wrote in 1957, was on the one hand "the largest one could afford, but with a limit of 15 tonnes displacement". In other words, about 40 feet long, eleven feet wide, with a draught of slightly less than 1.80 metres. Aft with a short, overhanging transom for more buoyancy as a direct response to the wet cockpit of his third "Wanderer". With space on deck where you can sleep outside in the tropics - much missed on the "Drei"; a cutter rig with a short bowsprit - for plenty of sailing power; and with plenty of engine power - anything bigger than the 4 hp Stuart-Turner of the "Drei". In short: a type of boat of which thousands were to be built in the seventies and eighties, although most of them were made of fibreglass.

For Eric, this was little more than a mental exercise at the time; he and Susan could not afford such a ship. And why should they? The "Three" had fully confirmed their trust and never let them down once.

Susan and Eric become repeat offenders

In 1959, they set off from England on their second circumnavigation, again along the classic circumnavigation route, soon christened the "Hiscock Highway". This time they set course for Mangareva in the East Pacific and crossed the 96th meridian a little further south than the first time. And again it gave them quite a hard time.

"At Susan's suggestion we turned in for six hours so we could both get some sleep. Took the jib down at 0600, unbelievable rolling at times, it even catapulted a saucer out of its holder. Everything is the wrong way round on this bow: galley to windward instead of leeward makes cooking extremely difficult, chart table to leeward sends blood to my head - and, as we both prefer to sleep on the right side of our bodies, our faces are pressed hard onto the mattress and our elbows, which were causing us problems before, are paralysed ... Susan's stomach is better, mine is still annoying."

This logbook entry from 6 March 1960 makes me wonder: How can it be that I hardly feel this rolling and lurching? Am I really so insensitive and insensitive to movement? Or have I - since I hardly ever had to steer by hand on long voyages, except in polar waters with drift ice - simply never experienced the same excessive and continuous exhaustion as she did?

Despite shortcomings, "Wanderer III" remains favourite yacht

Laurent Giles gave his own answer to the apparent shortcomings of the "Wanderer III" with the design of his 30-foot Wanderer class. It is slightly wider, with a higher freeboard, a continuous deckhouse instead of the stepped one, and therefore with a larger cabin. I have never sailed a Wanderer-class boat, but in purely aesthetic terms - for me - there is simply no comparison with the "Drei".

Eric's lamentations may ultimately have prevented the "Wanderer III" from becoming a popular design with a correspondingly large number of replicas - which would have been expected, given that her voyages inspired entire generations of sailors worldwide. And yet, after 110,000 nautical miles sailed together and despite all the misfortunes at 96º W, she remained Eric and Susan's declared favourite yacht for the rest of their lives.

Third circumnavigation with new owners

Between 1974 and 1979, Gisel and Chantal sailed "Wanderer III" around the world for a third time. Unlike Eric and now me, Gisel hardly ever wrote a word and took very few photographs. Nevertheless, of the three of us, he is the real storyteller. His powers of observation and ability to immerse himself in the smallest details and convey them across a table over hot tea and fresh brown bread are unrivalled. He tells wonderfully intricate stories that are a pleasure to listen to, but not to read. That's how I got to know him in Kiel in 1982: as a storyteller and - it felt like - the only German with an inordinate amount of time.

Not long before I met him for the first time, he had sailed "Wanderer III" single-handed through the Indian Ocean while his partner Chantal was ferrying another yacht - and tragically died in the process. After 15 years of long-distance sailing, most recently on "Wanderer III", Gisel said he would probably not be sailing for a while. I left him a phone number - he had dialled it later that year and said he wanted me to keep "Wanderer III" moving on the oceans. It determined the direction of my life.

Today, in his mid-seventies, he lives on Mallorca, where I last met him. Apart from the encounter in a crazy dream in which he made the astonishing remark: "Thies, I forgot to tell you that 'Wanderer' has a cellar", I hadn't seen him for a whole eight years.

Few footprints of Gisel and Chantal

That mysterious extra storage space had unfortunately remained as much in the dark as parts of his "Wanderer" story. I only had one tiny clue about Gisel and Chantal's rendezvous at 96º W: the sketch of a freighter near the equator on the chart of the Eastern Pacific that he had passed on to me.

There stood Gisel on Mallorca, tall and slim, a warm smile on his face, his upper body slightly bent forward as always; he carried this adaptation of "Wanderer's" small dimensions into his later life. Both Gisel and Chantal were too tall to fit into the Wanderer III, which was designed for the shorter Hiscocks. They could not stand upright in the cabin and could not stretch out fully in the bunks. Where our wood-burning stove stands today, right next to the mast, their feet dangled out of the bunks and hung in the air.

The fact that Gisel is not a man of extensive modernisation and repairs was "Wanderer's" - and our - good fortune. He preferred to devote himself to the details. He was able to fully immerse himself in carving small things such as the pockwood handles of our winch cranks or cleats; and Laurent Giles' logo was screwed to the bulwark with not seven, but 27 bronze screws. All these things are still with us; only his perfect paintwork has not remained.

Lost and living memories

Sitting with Gisel in his Mallorcan orange grove, it was now me, not him, who was interested in the details. Instead of German brown bread we had olives, instead of tea we had wine, while Kicki and I listened to his stories for days on end. In August 1975, for example, he replaced all the galvanised pontoons and the bow and stern pulpit with stainless steel ones at the renowned Goudy & Stevens boatyard in East Boothbay, Maine. And the stainless 1x19 forestay, whose skilful splicing I had admired for many years? He had it made simply because it was feasible. And what about that sketch of a freighter at 96º W on the chart? I don't know, he couldn't remember it. "But," he sank into thought, "the passage to the Marquesas was pure magic."

Just like for us.

Our first trip to the Pacific was the fourth for "Wanderer III"; and her third between the Galapagos Islands and the Marquesas. She steered herself, the sheets required almost no corrections - it was like a repeat of the Hiscocks' perfect sailing day on Friday the 13th in 1953.

On my map - Gisel's old one - two lines with very evenly spaced crosses ran parallel to the equator from the Galapagos Islands to the west. They marked Gisel's and Chantal's course and now ours. Each new cross drawn daily for our midday position stuck close to one of Gisel's and Chantal's; our westbound marks were almost the same.

Race on the nautical chart

On the spur of the moment, more out of curiosity, I plotted the daily positions of Eric and Susan's trips, and suddenly the journey became a race, sailed in the same boat but in different decades - by the Hiscocks in 1953, by Gisel and Chantal in 1976, and by us in 1991. Sometimes we were in the lead, sometimes one of them - until finally, 300 miles off Nuku Hiva, we were hopelessly stuck in a lull. Even when the wind returned, we were soon to fall further behind - due to a slowdown of a completely different kind.

Like hardly any other boat, "Wanderer III" has characterised the pattern of classic circumnavigations. You leave your home harbour, sail around the world in a rapid succession of passages along the trade wind route, touching one place on the way to the next and returning within a predetermined period of time. This is typically around three years. Both the Hiscocks and Gisel and Chantal followed this pattern. And, up to a point, so do we in the broadest sense.

The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway

My illness with hepatitis B then changed a lot of things. I fell ill on an uninhabited Tuamotu atoll called Motutunga. We were alone, with no means of communication, nobody knew where we were. Weakened by the hepatitis, it was impossible to leave the atoll. It was too beautiful for that. It held me physically, but also metaphysically captive - the tonal balance of the constant trade winds over my bunk was hallucinatory. Looking back at Motutunga, I realise that it is right here, in my tenth year on Wanderer, that we really merged into something completely separate; into her third story - the one with us and ours with her.

My hepatitis triggered something that made us break with the traditional Hiscock continuum - from Panama to New Zealand in one season. In the early 1990s, as a foreign yacht in French Polynesia, you needed a valid reason to be allowed to stay there during the cyclone season. When we arrived, still clearly weakened, I met the criteria. But six months non-stop in Tahiti or even on Moorea were not very appealing. As soon as I was halfway back in trim, we sailed northwards to the Kiribati Line archipelago on the equator during the cyclone season.

Once there, we stayed - and all plans fizzled out. The tight cruising corset of the Hiscock Highway - the standard trade wind route around the world - and the remnants of a schedule-orientated impatience in me - they dissolved and disappeared. We had sailed into the slow-beating heart of the Pacific. Without my hepatitis, we would probably have continued the journey to my Samoan family and on to New Zealand. Instead, we were now fully absorbing the slowness of the Pacific and its inhabitants; we were in an ocean full of time. This experience set the standard for all our subsequent voyages in the Pacific, the Indian Ocean and later in the Southern Ocean.

From a yacht sailing around the world, it became a platform for being in this world

It also had a significant impact on my perception of "Wanderer" itself and the meaning it had for me. All yachting narcissism was overcome because of its insignificance. From a yacht travelling around the world, she became a fantastic platform to be in this world.

Before I left Europe on "Wanderer III" in 1987, I was still harbouring the idea of building a larger wooden boat myself after my return, one in the style of Laurent Giles' "Dyarchy", traditionally planked. The idea was to sail it hard after completion, set course for Chile, caulk the hull again and then coat it with copper where copper should be cheap. The second part of my idea revealed glaring gaps in my understanding of macroeconomics.

In 2000 in Chile, nine years after the decelerating diversions to the Line Islands, we had long realised that the only copper-plated boat we would ever own would be "Wanderer III". Because of her character, her simplicity, her small size and aesthetics, because of what she allows us to do, and because of her nature to be perfect for all her imperfections. Grow - yes, but not in size. If you accept the challenge of being satisfied in the small and simple, then there is hardly a better boat.

A whole range of adjectives for 96º W

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, after two years in the Falklands and South Georgia, we had just painstakingly cruised northwards through Chile's Patagonian channels. Despite a few broken frames and colossal blows in the Southern Ocean, she had never leaked. We wanted to keep it that way and intended to carry out preventive repairs in New Zealand. With this in mind, we set sail from Puerto Montt, Chile, into the Pacific for our fifth encounter with 96º W.

The four previous meetings, all via Panama, had either been "magical" - Gisel's and ours - or "a bit too rough" - the Hiscocks'. This time, "Wanderer III" was turning on her own axis; we were drifting in the doldrums. Under a seemingly endless grey sky, a constant breeze had kept us going for several hundred miles west of Chile's coast on a north-westerly course to latitude 17º 30' south. But then, on the 22nd day at sea, we slid onto a magnet. At least that's what it felt like. Everything stopped suddenly, almost seamlessly: the wind, our movement, even the grey of the sky. It was as if we had sailed into the middle of a still, unchanging dreamscape.

"For the first time, overwhelming farsightedness, clearly contoured, with sharply drawn mountain ranges nothing more than unexplored cloudscapes, dream islands in the distance - reality and dream interpretation indistinguishable from nothing," I wrote in the logbook on 7 August 2000. All that remained for us was to drift powerlessly. If it was the 96º W's sole intention to invent days completely detached from human ambitions and to let us recognise them through "Wanderer", then it succeeded.

Course to New Zealand for restoration

The calm only lasted four days, but it gave barnacles a chance to take over the underwater hull. This in turn extended our passage to Penrhyn in the Cook Islands to 54 days. From there we sailed to New Zealand and put "Wanderer III" ashore for her half-century facelift. Quiet days were rare from then on. Every single day for well over a year was dedicated to her restoration.

It was here in New Zealand, after the Hiscocks had sold everything in England in 1974 and had become homeless sea nomads on their new steel ketch "Wanderer IV", that they received a letter from Bill Tilman. Tilman was another sailing icon of the time and had been the first to sail the high Arctic and Antarctic latitudes on various Bristol Pilot cutters - most famously his "Mischief". "I am not surprised," he writes to Eric and Susan, "that you are at a loss for new destinations for your next sailing voyages, as you have explored almost every corner of the globe. With the exception of where you are now, the only peaceful areas left are those that are still uninhabited by humans."

Declared goal: "Wanderer III" should not need a slipway for many years to come

If this was his sentiment almost half a century ago, how much more does it resonate in our reality today. Tilman's places of unpeopled nature have long attracted us. We intended to spend long periods in the Ultima Thules of our Earth, where repair is either difficult or non-existent. I wanted Wanderer III to require no structural intervention or even a slipway for many years. I was convinced that, although small and made of wood, she could survive in the rugged high latitudes into old age due to her original construction standard and the longevity built into her. Ultimately, these gifts also form the backbone of each of her eight 96º W crosses. They are the reason for her dry bilge.

Their longevity is based on a triptych of factors. First and foremost, the combination of owner, boat designer and boat builder. Eric Hiscock knew exactly what he wanted in 1952, Laurent Giles was an internationally renowned yacht designer, and William King's shipyard in Burnham-on-Crouch delivered the best quality in the country. The boat builders used carefully selected and dried wood, and the wood joints were perfect.

The second element of the triptych is the construction. The slender Karweel hull has very narrow Kalfat seams, an elm keel, elastic Sitka spruce fore-and-aft strakes, sterns, deadwood and deck beams made of grown oak - and not a drop of glue. The dimensions of all hull parts subject to particular loads, especially in the bilge, are oversized. The same applies to her hardwood panelling made of iroko. And then there are her metal connections; today they are almost exclusively made of copper. For a wooden boat, copper is almost like a source of eternal youth; all originally galvanised iron has been eliminated from the hull. And where copper is too soft to be used, as in the ballast keel bolts or metal floor cradles, aluminium-nickel-bronze is now used.

"Wanderer III" literally beckons to be groomed

But even this lifetime's advance of an exceptionally well thought-out design would not necessarily have been enough to allow her to sail more than 300,000 nautical miles in all the world's oceans without any problems if it were not for her three owners: Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and me. We filled her with voyages, we all lived on her, we admired her dearly - still do. It's not too big, on the contrary: it's small, pretty and harmonious. She literally beckons you to look after her. This is at least as important for its longevity as every structural detail. And, of course, like luck.

In 2003, on the very first voyage after the restoration of "Wanderer III" in New Zealand, we ended up on a reef in New Caledonia. Thanks to her new frames, her new copper plating, another repair and that all-important dose of luck, we were able to return to sailing. She survived a demanding test trip to Tasmania and on to New Zealand's sub-Antarctic islands without any leaks, giving us back the confidence we needed in her.

At the end of April 2005, at the beginning of the southern winter, we set off on a 71-day passage into the Southern Ocean from Dunedin, New Zealand, back to Chile. On the 59th day, we reached a position where God was playing chess with the surrounding highs and lows, but had obviously fallen asleep. Because without the slightest hint of change, it had been blowing at 9 to 10 Beaufort for days. We were lying at 39º S in a five-day storm. Five long days that we drifted back across longitude 96º W. Nevertheless, two characteristics of "Wanderers" that modern yachts no longer possess provided us with welcome comfort during these days: firstly, their ability to lie safely at anchor and secondly, the soothing muffling of the external howling in their cabin.

Double turning as relief valve

She turns unusually well, even under trysail alone. The ten-tonne weight of her hull in combination with her long lateral plan reduces her drift; above all, this makes it possible for her to sail upwind from a lee shore even at 40 knots under sail. This is an absolutely essential quality for a small, lightly motorised yacht like "Wanderer III", especially along the coasts in the high latitudes. It is the main reason why she can be sailed in these regions at all.

Once we had turned it round, it felt as if we had activated a relief valve, released the pressure and entered a state of alert slumber. When we closed the hatch and slipped down into the cabin, the over-excited howling outside lost its bite.

It is below deck, especially in storms, that the sound of a boat either encourages confidence or releases nerves. "Wanderer's" soothing sound kept all tension and irritability under control.

Sixth and seventh rendezvous

Something else, however, was worrying us. Our little Sony receiver had issued a rather absurd message: "Warning of falling spacecraft elements on 16 June 2005, between 0100 and 2300 UTC within the coordinates ..."

Exactly where we were. "What else are they going to throw at us?" shouted Kicki. But at some point, our chess-playing god made a move and allowed "Wanderer" to leave their lonely longitude behind for the sixth time.

The seventh rendezvous followed on New Year's Day 2006 at 25º 30' south - and was the diametric opposite of the sixth. Just as lengthy and awkward, only this time with absolutely no noise and zero wind - courtesy of the expanding Easter Island High. Compared to that five-day crossing, the two days we spent stuck on the line seemed like a hasty pit stop.

Turning point at 96º W

Whenever "Wanderer" encountered 96º W so far, she had left all signs of human activity behind her. That changed now. What I observed from the deck was more unsettling than any storm. I leaned my upper body over the railing and stared vertically into the sea to a point where the sun's rays converged concentrically in the deep blue. At some point, I focussed my gaze on tiny particles floating in the upper part of the sea column. Plankton. Or so it seemed.

I grabbed a bucket, dipped it in the sea and ... fished out fibres. What appeared to be plankton were actually plastic particles. The deep blue upper layer of the sea was strewn with a loosely woven carpet of the tiniest particles of our civilisation's rubbish. Everywhere I looked, I discovered plankton-like fluff and shreds, ejected by the achievements of a buzzing world somewhere else. This was not the densely populated North Pacific with its famous rubbish vortex, but a place far from human centres. This was where Thor Heyerdahl sailed through an almost untouched ocean with his "Kon-Tiki" in 1947. And where, a few years later, "Wanderer III" showed many of us our course for the first time.

At the beginning of the 1950s, the oceans were still unspoilt in their diversity of life. This is the time when "Wanderer's" story begins, around the same time as the ecologically precarious acceleration of consumer behaviour in our society. Since then, practically all our activities have flowed in one way or another into the sea that stores our excesses. Below deck, amidst its unchanged furnishings from another era, "Wanderer" may seem like a time machine. But on deck, surrounded by the sea, I think of her as a contemporary witness. Because she has witnessed the evolution of our current ecological dilemma from her well-travelled vantage point from the very beginning. For us, she is the ideal partner to peel back all these layers of the diversity of life - in beauty as well as in sorrow.

I realised that I could only see the carpet of plastic fluff when it was calm. As soon as it breaks up, it tears, escapes the eye and the sea surface shines and sparkles. Movement transcends so many things, including pollution.

Change and the future

I would certainly not have understood all this if we had hurried on this journey and not drifted windlessly. "Wanderer III" will never have a large engine, never carry much diesel. A large double berth is also out of the question. Like Eric and Susan, Gisel and Chantal, Kicki and I have learnt to live well with their spatial and temporal limitations. They suit us, we see them as an asset, we simply give them a lot of time and as a result we see other things and many things differently than if we did not.

Until recently, longitude 96º W was not so easy to reach from the Falkland Islands due to Covid, unless it was upwind around Cape Horn. This restriction also required time, patience, as perhaps the entire view of "Wanderer's" era required a moist eye that keeps up with the times. How much will have changed when she next finds herself with us at 96º W?

It will be wet, quiet, windless or stormy and - as always - no place to stay. But - I hope - its remoteness can still be felt, even in me.

Also interesting:

- Spectacular find in the Antarctic: researchers discover the wreck of Shackleton's "Endurance"

- Forgotten history: How a Bavarian builds a sailing boat and sails to India

- Portrait: Georg Dibbern makes history in German sailing

Most read in category Special

Wanderer III

Wanderer III was made famous by Eric Susan Hiscock during two cicumnavigations in the 1950’s. In their book, ‘Around the World in Wanderer III’ the couple set out from Yarmouth, England(1952) and circled the globe by way of the West Indies, the Panama Canal, Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, the Ascension Islands and the Azores, returning home three years later.

For more information on Website . Wanderer III has completed five circumnavigations and is sailed by Thies and Kicki Matzen. Below is their Youtube interview:

SHARE THIS:

- Yachts for Sale

Recently updated...

Write an Article

Covering news on classic yachting worldwide is a tall ask and with your input Classic Yacht Info can expose stories from your own back yard.

We are keen to hear about everything from local regattas and classic events to a local restoration or yachting adventure. Pictures are welcome and ideal for making the article more engaging.

With a site that has been created with the assistance of an international group of classic yacht enthusiasts we value your input and with your help we strive to make CYI more up-to-date and more informative than ever.

Please register and get in touch if you would like to contribute.

choose your language:

We’re passionate about Classic Yachts here at CYI, and we welcome submissions from all over the globe!

Captain, rigger, sail-maker or chef – if you’d like to write for CYI just let us know!

Email [email protected] to be set up as a Contributor, and share your Classic thoughts with the world.

ClassicYachtInfo.com has the largest database of classic yachts on the internet.

We’re continually working to keep it accurate and up-to-date, and we greatly appreciate contributions of any type. If you spot an error, or you have some information on a yacht and would like to contribute, please jump on in!

Don’t be shy…. Breeze on!

- Sell Your Yacht

Beyond the West Horizon

Running Time: 91-minutes

A film by Eric & Susan Hiscock In the late 1950's, very few "middle class" sailors had taken small sailing craft on long voyages. British Sailors, Eric and Susan Hiscock became pioneers in making long trans-oceanic passages in a small sailboat to what was then quite remote destinations.

The Hiscocks shared their sailing adventures in several books and made this 16mm color documentary about their 3-year circumnavigation aboard their 30 foot wooden sloop, Wanderer III. The couple departed from Yarmouth Isle of Wight on the 19th of July 1959 and returned on August 8th, 1962. Prior to their departure, the BBC provided some camera training, a 16mm windup camera, and 4000 feet of color film stock. During their 30,189 mile circumnavigation, Eric and Susan meticulously filmed their voyage and their many land falls. On their return, the BBC edited a 91-minute documentary based on a script and narration written by Eric. The finished film aired on BBC television in January 1963.

Free Extras: interviews with Lin & Larry Pardey about their friendship with the Hiscocks; and Thies Matzen and Kicki Erickson, longtime adventure sailors and current owners of Wanderer III, the vessel sailed by the Hiscock and featured in their film.

From his childhood, Thies Matzen had dreamed of becoming a wooden boat builder, and was enthralled with Eric & Susan Hiscock's Wanderer III and her voyages. As a young man, he was able to purchase Wanderer III and restore her to better than original condition while maintaining her classic rig and features. For 25 years, Thies Matzen and Kicki Ericson have sailed more than 135,000 nautical miles aboard Eric and Susan Hiscock's iconic 30 footer. Here is their story about Wanderer III.

No products in the basket.

Wanderer III

$ 35.00 – $ 1,020.00

Design No. 0164

Built for: Eric & Susan Hiscock Builder: W. M. King, Burnham on Crouch, England Date designed: 1951

Principal Design Data

L.O.A: 30’ 3½” (9.23 m) Datum: 26’ 4½” (8.04 m) Beam Max: 8’ 5” (2.56 m) Draft: 5’ 0” (1.52 m) Displacement tons: T.M.: 8.0 tons Ballast ratio: Sail Area: 597.0 sq. ft Rig: Bermudan sloop

After many years of sailing their 1936 Napier built cutter Wanderer II , Eric and Susan Hiscock naturally turned to Laurent Giles & partners for her successor Wanderer III .

One of Eric Hiscock’s main design specifications to Laurent Giles was that Wanderer III must have as much volume as possible for a given cost. This therefore dictated a moderate forward overhang with a transom stern, and had the advantage of being able to fit a trim tab vane steering gear which would be necessary for short-handed ocean passages. Although it was widely believed that Laurent Giles based the lines of the hull on an existing yacht Kalliste a 7-tonner built in 1938 information in the Laurent Giles Archive has recently revealed that the lines were actually developed from those of the 26’ 3” w.l. one design sloop which Giles had designed a year before in 1950 as a replacement for Kalliste for Mr D. W. Le Mare.

We are currently updating the online purchase facility. For those of you who would like to buy copies of the original historical drawings, plan for the construction of scale models, stock plan sets for full size construction, study notes or our brochure please contact us stating which design and items you require. We will do our best to help.

If you want to make your purchase by using PayPal account or credit card, please choose 'PayPal' at the 'Check out'. We can also take payment by Bank transfer, for further information, please contact us.

Additional Information

Individual drawing copies.

Please download and print the drawings list for Wanderer III, Individual plan copies cost $85.00 which includes standard airmail. Please contact us using the link for information on how to order.

Study Notes

16 page A4 format colour booklet containing many small scale drawings and photographs as well as technical data and an abridged specifications of Wanderer III. Construction scantlings are of the original carvel hull.

Model Plans

Full set of Stock Building Plans

A replica of Wanderer III can be constructed from the original 1951 drawings for carvel construction for which full lofting, construction, rigging and outfit drawings will be provided.

Poster & Art Prints

You may also like, check out a few related products.

July / August Issue No. 299 Preview Now

WANDERER III

ACCESS TO EXPERIENCE

Subscribe today.

Subscribe by June 23rd and your subscription will start with the July/August 2024 (No. 299) of WoodenBoat .

1 YEAR SUBSCRIPTION (6 ISSUES)

Print $39.95, digital $28.00, print+digital $42.95.

To read articles from previous issues, you can purchase the issue at The WoodenBoat Store link below.

From Online Exclusives

STING RAY V

From Lobsterboat to Lobster Yacht

Laminated Frames Part 1

Whiskey plank.

My Six Cruising Sailboats—#3 IMAGINE

From the community.

1964 Chris Craft 16 ft with custom trailer

PRICE REDUCED $10,400 - Beautiful, reliable boat Complete restoration.

Custom 37’ Garden Ketch

Bill Garden custom designed 37’ Ketch, built by Far East Yacht Company 1965.

Oselvar Faering

This is a beautiful three year old Oselvar Faering that excels at both rowing and sailing.

Classic 44' Tacoma Boatworks Trawler 1948

“Ronny” was built at the Tacoma Boat Works in Seattle in 1948.

- BOAT OF THE YEAR

- Newsletters

- Sailboat Reviews

- Boating Safety

- Sails and Rigging

- Maintenance

- Sailing Totem

- Sailor & Galley

- Living Aboard

- Destinations

- Gear & Electronics

- Charter Resources

- Uncategorized

The Rescue of Wanderer III

- By Thies Matzen

- Updated: March 11, 2010

Wanderer III 368

After a two-year refit of Wanderer III and a rough, nine-day passage from New Zealand to Nouvelle-Calédonie, we now had nothing but turquoise water on our minds. Kicki Ericson, my wife, and I planned to spend a few weeks of lazy indulgence on the island, then work to fill the kitty before continuing on to China. It was July 2003, and we were finally out voyaging again. As we approached our first landfall at Nouvelle-Calédonie, we saw the solid shape and the bright flashing light of the Amédée lighthouse. It’s part of a leading light through Passe de Boulari, the main pass through the reef into Nouméa. Ten years before, I had entered here in daylight. My chart had been old then, and since those days, time had been rough with the black-and-white copy of an original in too small a scale. I’d changed Wanderer’s frames and floors and much else but not, unfortunately, this chart. My old pencil marks on the chart had remained sharp, but the print was fading.

The leading lights were there, on Récif Toombo and Récif To, both of no relevance once we were on course. I fumbled with the chart-table lamp to read the small print around Récif Tabou, for that one mattered. Once we spotted it, we had to turn to port and head straight north for it, and leave the leading line. I followed the nearly indecipherable dotted arc around its light, partitioned into sectors. White; obscured. White again? The chart wasn’t clear. When I headed back up into the cockpit to wait for the leading lights to fall into line, “white” was imprinted in my brain. Just off Amédée lighthouse, a tiny touch to the west and on the correct bearing from where we were, I spotted it: a light. White! Récif Tabou! I was hooked.

Having picked up the leading lights five miles off, we were comfortably holding the heading in a moderate breeze. I saw smaller red and green blinking buoys to starboard that my old chart didn’t show; I interpreted these to be new guides through a secondary entrance, and in fact, that’s what they were.

But with lights added, had others been changed?

How on earth could these lights have failed to reawaken the caution that had always served me well? We shouldn’t even be close enough to see them. Why didn’t I do as I’ve always done, over so many years spent in the reef-strewn waters of Kiribati, Micronesia, and Indonesia? Impeccably timing critical passages with the full moon, never taking risks, absolutely never going in-anywhere-at night. There was one resolution that my ownership of Wanderer III since 1981 had deeply ingrained in me: A storm, a freak incident, c’est la vie. But I was never to lose her through bad seamanship.

At other times, we hove to. It’s so easily done. And Wanderer III does it so well, in storms, in bad weather, and off tricky landfalls. An underrated element of seamanship, hoving to is vital when sailing requires vigilance, alertness, and good judgment rather than dependence upon electronics.

Surely this wasn’t a remote pass in a banana republic. This was Nouvelle-Calédonie, Europe in the Pacific; this was France. In 1961, the Hiscocks had made it through here on Wanderer III at night.

But we weren’t the Hiscocks. And on that night, something went critically astray in my mind and my focus. The pelagic harmony I once knew, now two years unmaintained, had gone. After having given Wanderer III a new skeleton, she was definitely in better sea shape at the age of 50 than I was. I lacked the mental agility of the sailor that I’d been. As in a game of roulette, my vision had rotated round the dark plate of ocean and got stuck in one section: the white light. And I no longer took other things I saw into account.

With my hand on the tiller, we carried on toward the invisible cut through the reef. Whatever current there was, it was easily countered so that we could repeatedly line up the lights. The sails pulled well. We slipped through the outside barrier with no visible signs of breakers, but we believed we’d heard them a wee time back. But how far away were they?

I saw a green light. When will the white light on Tabou finally come to bear 360 degrees, so we can turn, I wondered. It can’t be long. I glanced at the hand-bearing compass on the foredeck, and I was about to say “Now” to Kicki-and then we hit. Something. Something real hard. Whatever it was, I kept waiting to sail over it. But we didn’t. I felt a dreamlike denial. Pull down the sails! Your hands immediately do the right things, but your mind is locked in disbelief. Yet the pounding that sent shockwaves into our bone marrow was real, the walls of spray shooting across the deck and down the companionway were real, the surrealistic heel was all too real.

Every third or fourth swell was bigger and lifted Wanderer III more violently. The hull was crashing and grinding on the reef. I grabbed a light. It lit up coral heads and a shrunken horizon of breaking waves. I needed to do something to shift me back into reality, the good one. I reset a sail, but it didn’t help. At last I threw an anchor, then settled into the confusion, the swell, the unforgiving harsh reality around me and searched for a rational lifeline.

Down below, Kicki, braced between the table and settee with the VHF mike in hand, was upset.

“Impossible! They don’t stop talking. They just don’t listen,” she said. We couldn’t make contact. I grabbed the binoculars and climbed back outside. The loom of Nouméa was visible 14 miles to the north, and I saw another green light not far off. Amédée’s leading lights were still in line, but suddenly close.

I swung the binoculars farther around to that bright white light-and to a much weaker one beside it. It took a while for this to sink in. “Unbelievable,” I thought. “Masts! Two yachts anchored behind a reef.” We’d clearly sailed too far. Where was the light on Récif Tabou? It was invisible.

Kicki and I cut loose our solid dinghy. I left Kicki and the violently lurching Wanderer III, each thundering thud rattling their bones. I headed off into the dark.

I rowed half a mile over choppy waters and coral toward an anchor light atop a mast. Then I rapped on the hull of a luxury yacht-ridiculous, unexpected knocks to anyone who heard them an hour before midnight at the edge of Nouvelle-Calédonie’s barrier reef. Three people came out. Under the flood of the spreader lights, I resembled the seagoing equivalent of the yeti, with some Rasputin and Eric the Red thrown in: a strange, sodden being all hair, ripped wool, and oilskins. Only the despair in my eyes must have convinced them that I was human. I was asked on board Coconut, and there I poured out my story.

The captain’s name was Nick, and he said that time was precious: The tide would soon ebb. He’d try to pull us off. We might stand a chance if we could heel Wanderer III over by the mast. Claude, a French sailor on a neighboring catamaran, offered to pull as well. The two boats, with 65 horsepower between them, pulled on long ropes from the mast. Wanderer III crashed from port to starboard, swung her bow around, and much water sloshed inside. But she wouldn’t budge a meter, and we had at least 20 to go. We gave up.

Meanwhile, the owner of Coconut had reached the Gendarmerie Maritime in Nouméa and, though no life was in danger, convinced them to come out. Thus we were given a second chance on that night, as long as Wanderer III could withstand the pounding of the swell. We were desperately hopeful to have them try to pull us off while the tide remained high. But their efforts fell short. They floated down a line, and their boat drifted into ridiculous pulling angles that made me cry out “Come on, come on, now!”

Then they asked for their line back and offered, instead, to let us spend the night aboard their ship. They planned to anchor close by. Our last feeble hopes dashed, there was little we could do on Wanderer III. To Kicki’s surprise, I accepted their offer to leave our home. We packed a few things-documents, diaries, photos; as an afterthought, dry clothes-and said good-bye. There was water swishing over the floorboards. It seemed only a matter of time before Wanderer III would be lost. At 0300, they took us off our pounding boat, our dinghy in tow.

The tone aboard the anchored Gendarmerie ship was strangely subdued. Professionals, they left us to ourselves. Closely bonded as we were with our boat, there was no knowing where this would lead us, as a couple-without Wanderer III. Men in wetsuits passed wordlessly around corners to disappear outside. We heard splashes but gave them no notice.

Only later we learned that the Gendarmerie, in preparation to pull us off, had themselves touched the reef. While going beyond what was their duty and trying to save a boat rather than lives, they’d damaged their prop. Headquarters ordered their immediate return to Nouméa, which gave Kicki and I the chance to split up to save the boat. We had to. Kicki spoke some French. “You go. Try to get help, a tug, anything,” I said. I took the dinghy and rowed across to Coconut, where they’d offered me refuge. Nick and I were calm and spoke little. He showed me a cabin, a cave to hide in, and I closed the door.

As soon as I’d stowed myself beneath a layer of fresh linen, I noticed something flickering. It was the shadow of a moving flag, passing through a skylight onto a bathroom mirror and into the depth of my soul. It totally captured me; I can still see it today. Well past 0400, the moon had finally risen, making visible the flag and, so, the wind.

My mind was spinning in awkward circles: “Must rebuild her, if only the keel remains. Must take it, start anew. Three to five years. Impossible. Or something else? Never! In New Zealand? Money? Us in Europe? Imagine.”

Every time I opened my eyes, the shadow was there, reminding me of a reality that left me incredulous. By the way the shadow flickered, I could judge the force of the wind. Sharpened contours meant more wind, which meant doom. I feared them. I did fall asleep eventually and awoke at the break of dawn with the fluttering image gone. Squinting my eyes, I looked for Wanderer III in the haze. Worried by what I made out, I hurried to the bow for an unobstructed view. Could it be? With the night now gone, was her mast gone, too?

Just when the early morning haze was playing tricks with me, Kicki arrived in Nouméa. At 5:45 on a Sunday morning, with not a penny on her, she was on a mission to find a tug. Eventually she was deposited at the entrance gate to Nouméa’s port, guarded by a friendly local. Leaving it unguarded, he drove her to the tug-company offices, which were just being locked by two employees, a Kanak and a Frenchman. Their tug was sitting right outside, but their boss couldn’t be found. After hearing her story, they then phoned three other companies, each time relaying a string of questions and answers.

The first wouldn’t do salvage of anything longer than six meters. The second wouldn’t go as far as Amédée. The third said that they could do it, but not today; maybe tomorrow. Meanwhile, her boat was breaking up on the reef. Kicki could no longer hold back her tears. Aren’t there any other options? The military? What’s the phone number? A pause, a sigh, and then the Kanak said to the Frenchman: “Bien, alors, Monsieur Gallo.” Let’s try Monsieur Gallo. His was the cowboy outfit, the company that none of the professionals liked. They dialed his number and asked a few questions. In 15 minutes, he would be there, and he was.

A white-haired man in his 50s with burnt-red facial skin and a long scar across his throat soon asked Kicki to step aboard. They were off to the vessel on which the skipper, Willard, lived. Willard, with long blond hair and a Hawai’ian shirt, looked like a bird of paradise and attempted a peculiar dance. Swinging one leg over the railing, he fell over backward, disappeared, hit metal, bounced up again, and climbed aboard. When he noticed Kicki, he cracked a wide grin. “Bonjour, miss.” Willard the skipper was clearly well oiled. What did it matter? By 8:15 on a Sunday morning, Kicki had a tug. But she didn’t know whether she still had a boat.

She did. Having for six hours channeled all her energy toward being where she was now, on a tug en route to Amédée, she’d finally contacted Coconut to learn the news about Wanderer III. The news was emotional. On the two-hour trip, Monsieur Gallo was sympathetic. He also asked all the relevant questions: How many masts? Strong tying points? What wood was she built with?

Then, near the end: “And you can pay?”

Kicki looked him in the eyes and replied honestly: “We will find the money.”

On Wanderer III, I knew by then that a tug was coming. Nick had motored over to tell me. Earlier, when I couldn’t see the mast, I’d jumped into the dinghy and rowed off with desperate strokes. To my relief, I’d soon found that the mast was standing but that Wanderer III, lying quietly in less than a foot of water, was excessively heeled.

Barefoot, I pulled my dinghy over hundreds of meters of exposed coral heads-it was crazy. At the end, I had to climb the steeply heeled structure that was my home. I could see the 30-meter scrape that she’d cut diagonally over the reef. Her mad dash had stopped four meters short of a mean-looking group of coral heads. Inside, nothing moved, the amount of water in her hadn’t increased, yet I could only guess the state of her planking. Still, I was hopeful. Alone, I dove and placed more anchors onto the reef, all with chain. In case she might have sprung a plank, I emptied and plugged the water tanks, blew up the inflatable, packed everything inside Wanderer III that would float, and took out what wouldn’t. Perhaps she might find equilibrium below the surface and could be towed somewhere safe. Then, to make sure that she’d be pulled from her most secure point, Claude from the catamaran helped me rig a bridle through the aperture for the prop; its pulling point would be suspended just above her waterline by the bow.

We’d barely finished when Willard maneuvered the tug into position upwind. All that we needed to do now was float down a heavy hawser with a huge shackle, attach it to the bridle, and pull. Willard began gently, then increased the power. Nothing happened. The tug would nose forward, power backward, but the rope only made noise. Three times Willard tried, to no avail. But on the fourth try, the bow pulled around. “Voilà, la bijou. She’s coming home,” Kicki heard Willard say. On Wanderer III, I listened to grinding grunts that I never knew a boat could make.

Finally, she took a deep dive back into the sea. And stayed afloat. And took on no water. With the fine touch of a drunken bird of paradise, Willard had pulled Wanderer III back into her element and our lives.

That evening, we should really have been sitting on some friend’s boat, lamenting the loss of Wanderer III. Instead, our paraffin lamps glowed, our chronometer ticked, and our cooker hissed. And as we prepared a simple meal, everything was in its familiar place: the potatoes, the plates, and the pots. The normality was nearly incomprehensible. True, everything was sodden, and the cabin was in chaos. Big repairs lay ahead of us, and we had big bills to pay. We didn’t care. We had her back. And something beautiful was about to come our way.

Read about the repair of Wanderer III in the conclusion of this two-part series next month.

- More: voyaging

- More Uncategorized

Schooner Nina Missing

Editor’s Log: Pitch In for the Plankton

West Marine Announces $40,000 Marine Conservation Grants for 2013

Sailboat Review: Vision 444

When the Wind Goes Light

Sailboat Preview: Lagoon 43

Sailor & Galley: Ice Cream, Anytime

- Digital Edition

- Customer Service

- Privacy Policy

- Email Newsletters

- Cruising World

- Sailing World

- Salt Water Sportsman

- Sport Fishing

- Wakeboarding

- Yachting World

- Digital Edition

Sailing the Falkland Islands: A life-changing voyage on board Pelagic

- January 22, 2020

Silvia Varela reflects on how a farewell sail around the Falkland Islands on Skip Novak’s Pelagic became a turning point in her life

Photo: Sergio Pitamitz / Getty

In spring 2016 my partner, Magnus, and I delivered Pelagic , one of two yachts owned and run as a high-latitudes adventure charter boat by former Whitbread Round the World Race skipper and Yachting World columnist Skip Novak, from Puerto Williams in Chile to the Falkland Islands.

Having sailed to Antarctica , Cape Horn, and the Chilean channels during the southern summer, Pelagic was due to overwinter in the port of Stanley. This delivery was also a farewell for Magnus. After many years skippering Pelagic and her big sister Pelagic Australis , this was his final season in southern waters before embarking on new projects.

The Falkland Islands lie in the South Atlantic, at 52°S and some 300 miles northeast from Cape Horn . During our three-day delivery, a lively downwind ride, Magnus told me about his love for the place and the exceptional people he’d met there over the years.

Magnus studying the pilot book for the Falkland Islands inside Pelagic ’s pilothouse. Photo: Silvia Varela

The archipelago comprises the two main islands of East and West Falkland, as well as numerous smaller islands. Usually under time pressure of charter schedules, Magnus had only visited Stanley and a few other sites, but the places in between make fantastic cruising grounds with safe anchorages.

He dreamt of exploring the dramatic landscapes and abundant wildlife. As a photographer, I too am drawn to remote places and barren, windswept islands, and as a longtime resident of Argentina, I was already curious about the Falklands. By the time we made landfall in Stanley three days later, we had firmed up a plan to come back.

Skip kindly lent us Pelagic so we could cruise the islands at our leisure, and less than a month later we were on the short flight back from Punta Arenas, Chile. But our fantasy of island-hopping in calm seas and idyllic weather was soon shattered.

Article continues below…

Sailing South Georgia: The inside story of Skip Novak’s 2018 expedition

We were eight days out from the south coast of South Georgia and once again we had skied smack into…

Skip Novak’s Storm Sailing Techniques Part 1: the Pelagic Philosophy

Yachting World goes round Cape Horn. Watch how we made our 12-part series about storm sailing techniques with expedition guru…

The problem is that Stanley sits at the far eastern end of the islands, in an area of severe westerlies, which pinned us to the dock for the next week, blowing relentlessly over 40 knots. We drove around Stanley in an old military Land Rover – ubiquitous as the sheep that dot the islands.

We provisioned, filled the tanks with water and diesel, met friends and got to know the pub very well. We waited and waited, and were beginning to worry that our trip might never happen. Finally, a week later, the forecast gap in the weather arrived. The wind dropped to 20-25 knots, and we sneaked out as quickly as we could.

The wind was forecast to blow from the south-west over the following days, so we chose to make our westing to the north of the islands, where the seas would be more sheltered. Given how unreliable the weather had been so far, we had no idea how long the lull would last, so our first priority was to sail as far out west as we could while the conditions were relatively benign, then cruise slowly back.

This made sense particularly in the light of our second priority: to travel under sail whenever possible. After many years working to schedule in the charter business, Magnus was determined to avoid motoring unless absolutely necessary.

With all of this in mind, we left Stanley, turned round the north of the island, and headed west. We sailed through the night, since the north coast of East Falkland offers only a few safe harbours, and none particularly remarkable. Our first port of call would be West Point Island, off West Falkland, to visit Magnus’s old friends and cruising legends Thies Matzen and Kicki Ericson.

It was a rough passage. On the first day we struggled to make progress, with 25 knots on the nose and a short, choppy inshore sea. The following day the wind eased off slightly, but obstinately maintained its direction.

We sailed as far as the west end of Pebble Island before heading south-west inside Carcass Island and finally north-west up Byron Sound and into West Point Cove at West Point Island. We arrived very late on the second night, in darkness, relying on instruments alone. It was nonetheless an easy entrance, and we anchored in eight metres in the middle of the cove.

The next day we were woken by Kicki’s singsong voice on the VHF, inviting us to come ashore for lunch. We were feeling rather dizzy after two bouncy days at sea, and both perked up at the prospect of homemade food, good company, and a long walk.

With high sea cliffs and abundant bird life – especially large colonies of black-browed albatrosses, as well as gentoo, jackass and rockhopper penguins, and striated caracara, known locally as the Johnny rook – West Point Island is one of the most popular cruise ship destinations in the Falklands outside of Stanley.

From left to right, Thies, Kicki and Magnus walking in the mist. Photo: Silvia Varela

For the last three years, Thies and Kicki have been running the sheep farm and looking after the tourists. Last summer they arrived in record numbers: Kicki told us that season she’d baked cakes and made cups of tea for over 4,000 cruise ship guests on their short stopovers at West Point en route to South Georgia or Antarctica.

Thies and Kicki greeted us in their sunny kitchen, which would’ve been perfectly at home in an English country house. We hugged like old friends; I was instantly at ease in their company. The couple have spent their entire adult lives sailing in Wanderer III , the iconic 30ft wooden sloop in which Eric and Susan Hiscock famously circumnavigated the globe twice.

For the last 15 years, they have focused mostly on the Southern Ocean. Most impressively, they lived in South Georgia, on board Wanderer III , for 26 months, from 2009 to 2011, and published an extraordinary photobook of their time there. In 2011, they were awarded the Cruising Club of America’s Blue Water Medal.

Pelagic and Wanderer III at anchor, seen from the garden of the farmhouse at West Point Island. Photo: Silvia Varela

We chatted about life, sailing, South Georgia, photography, literature; our conversation flowed into the evening. One evening after dinner, they invited us on board Wanderer III for coffee and more thrilling stories, from rolling the boat near Cape Horn, to the challenges and serendipity involved in procuring firewood in treeless South Georgia.

Wanderer was one of the cosiest spaces we’d ever been in – intimate, full of books, lit by paraffin lamps, kept warm by a wood burner. A real home, as charming and hospitable as its owners.

Our original plan was to go to New Island next, reckoned to be one of the most beautiful in the Falklands. In order to catch the tide, which can run up to six knots through the Woolly Gut between West Point Island and West Falkland itself, we left in the gloaming.

Shipwreck on the beach at West Point Island. Photo: Silvia Varela

We headed south-west under headsail alone on a sea as smooth as oil, motoring occasionally when the wind dropped below five knots. In the perfect silence of the morning, we could hear birds flapping their wings as they took off in the distance.

We altered our course many times, trying to anticipate where the next whale would surface, listening out for the otherworldly sound they make when they blow out spray. From that morning on, we were permanently escorted by dolphins. At one point we counted 22 all around Pelagic !

As we neared the island, we veered off course to take a close-up look at the Colliers, a striking pair of sea stacks that I wanted to photograph. We spent hours going round and round the rocks, under sail alone, just for fun. The sea stacks are made of layered shelves on which dozens of sea lions were enjoying the sun.

Magnus working the jib as we sail round the Colliers. Photo: Silvia Varela

However, with each lap of the yacht, the young males became increasingly vocal, until they finally drove us off their territory with their cacophony of barking and an intense stench.

We’d taken quite a detour to see the Colliers, and by the time we left, the sun was going down. Going to New Island would’ve meant doubling back on ourselves, so instead we steered Pelagic toward Beaver Island.

Beaver Island, the westernmost of the Falklands, is the home of southern high latitude sailing pioneer Jérôme Poncet and his family. In 1978-79 his Damien II was the first yacht to winter in Antarctica, and to this day remains the only yacht to have wintered so far south (67°45’S). Sadly, there was nobody on Beaver Island – Poncet was at Buckingham Palace, receiving a Polar Medal from the Queen.

A picnic and a rest on top of Beaver Island. Photo: Silvia Varela

Still, we hiked around the perimeter of the island and had a picnic at the top of one of the impressive cliffs, followed by curious and bold caracaras, and, at a more prudent distance, several flocks of reindeer. These are not native to the Falklands, but imports from South Georgia where, in turn, they were introduced by Norwegian whalers in the early 20th Century.

In 2002 and 2003, Poncet sailed 31 reindeer from South Georgia to Beaver Island on his yacht Golden Fleece . One can only imagine how disconcerting the voyage must have been for the reindeer, but they made it to the island and thrived.

Our delightful experience travelling under headsail alone from West Point Island set a precedent, and we continued under the same sailplan early the following morning, all the way to Pit Creek, on Weddell Island. The anchorage is very narrow and shallow, so even with Pelagic ’s lifting keel, we couldn’t get to the head of the cove.

The first cup of tea of the day. Photo: Silvia Varela

Dolphins known locally as puffing pigs, after the noise they make when they come to the surface, escorted our dinghy to shore. These are Commerson’s dolphins, only found in narrow passages; rarely offshore. Out at sea, the sleeker Peale’s dolphins take over, often leaping playfully alongside a vessel for hours.

By now we’d developed a cruising routine: arrive at a new anchorage; drop the anchor; take the dinghy ashore and go for a hike around the island. On our walk around Pit Creek we found vestiges of earlier human settlement – an old fishing buoy, the ruins of a house with only the fireplace and chimney still standing – but again we had the island to ourselves.

We weighed anchor at first light and sailed in light airs around the north of Weddell Island, toward Weddell settlement. We called into the bay hoping to meet the owners of the settlement, but nobody answered on the radio, so we decided to use the last light of the day to continue on to New Year Cove, where we spent the night.

Pelagic at anchor at Port Albemarle, famous for its abandoned sealing station. Photo: Silvia Varela

From New Year Cove, we sailed down the Smylie Channel. Crossing Race Reef and heading out to the open sea was very rough, with tremendous overfalls. Heading south-east, we passed the impressive cliffs of Port Stephens and Cape Meredith, toward the settlement at Port Albemarle, famous for its abandoned sealing station.

At the southern end of Falkland Sound, the channel that divides the two main Falkland islands, Port Albermarle has some of the most striking scenery in the Falkland Islands, with white sandy beaches and large patches of seaweed in prominent shapes and textures. We followed penguin footprints leading up from the beach and found a large colony of gentoo penguins, which were initially shy, but eventually waddled up to us, won over by curiosity.

On the way back to Pelagic , we were again escorted by puffing pigs, which seemed to be making fun of us by leaping up and belly flopping all around the dinghy, soaking us with icy water. We laughed and cursed them in jest, reminding ourselves never to forget that such moments are magical and a large part of why we live the way we do.

A Magellanic penguin on the beach at New Island. Photo: Philip Mugridge / Alamy

Although we were running out of time, Magnus was keen to explore Chaffers Gullet, a long, thin channel at the end of which there was a very appealing anchorage at the foot of a hill called the Little Mollymawk, which would’ve made for a perfect hike.

Motoring up this narrow channel – at times only 80m wide – took longer than we anticipated, and by the time we got to the anchorage it was almost dark, so we never made it off the boat. But it was a worthwhile detour that reminded Magnus of his childhood sailing dinghies on England’s Norfolk Broads.

Overnight, the barometer started to drop, and by first light the wind had got up and the air felt much chillier. We’d been very fortunate so far, but given what we knew about the weather in the Falklands, we didn’t want to push our luck. It was time to head back.

Pelagic approaching Stanley harbour. Photo: Silvia Varela

The days remained cool but sunny, and the winds light, as we sailed up Falkland Sound and on to Stanley almost in one stretch, stopping only at Shag Harbour and Salvador Waters.

At Salvador Waters – a large expanse of water joined to the Atlantic by a narrow channel of varying depth, about seven miles long – we encountered some interesting tidal effects: at one point, Pelagic was making 11 knots over the ground with the engine at idle! While this was a particularly extreme case, it was by no means unusual.

Throughout our circumnavigation, we’d been puzzled by the tides, which rarely seemed to do what they were supposed to be doing. Eventually, we concluded that, while there is extensive tidal information for the Falklands, it has no bearing in reality.

The Falklands can be tricky to navigate – the tides are especially hard to predict. Photo: Silvia Varela

Or, as our local friend Paul Ellis put it: “The tides around here just seem to do what they want: sometimes they come in and go out; sometimes they come in and stay for a few days.” The prevailing westerlies play a significant role, but seldom in the way one would expect.

Pelagic ’s chartplotter has a waypoint at the door of the Victory pub. I assumed this was a joke or a mistake until we tried to get back into Stanley in a hurricane-force westerly. It was a long day beating into the wind, by the end of which we were yearning for a pint and a hot dinner.

Still, we were sad to see our time on Pelagic and in the Falklands come to an end. In the three weeks since we’d left Stanley, we hadn’t seen or spoken to anybody other than Thies and Kicki; we’d had the wild, idyllic playground of the islands all to ourselves. We’d travelled mostly under sail, saving energy by going to bed at dusk and getting up at dawn, as well as reading by candlelight to avoid turning on the engine.

We’d learned to work together on a boat efficiently and joyfully, and we realised that the time we had spent with Thies and Kicki at West Point had planted a seed in us: what if we took up cruising full time? We’d both been travelling constantly for some years and were eager to call somewhere home, though we weren’t ready to stop exploring the world. The solution was staring us in the face: we would live on our own boat.

A few months later, we were heading for the Caribbean to start a new chapter on our 39ft steel-hulled home: Lazy Bones . And so it was that our time in the Falkland Islands heralded the start of our cruising life.

About the author

Photographer Silvia Varela and professional skipper Magnus Day live aboard their 39ft steel-hulled cruising yacht Lazy Bones . They offer charter bookings and polar expedition support via highlatitudes.com

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Eastern Europe

- Moscow Oblast

Elektrostal

Elektrostal Localisation : Country Russia , Oblast Moscow Oblast . Available Information : Geographical coordinates , Population, Altitude, Area, Weather and Hotel . Nearby cities and villages : Noginsk , Pavlovsky Posad and Staraya Kupavna .

Information

Find all the information of Elektrostal or click on the section of your choice in the left menu.

- Update data

Elektrostal Demography

Information on the people and the population of Elektrostal.

Elektrostal Geography

Geographic Information regarding City of Elektrostal .

Elektrostal Distance

Distance (in kilometers) between Elektrostal and the biggest cities of Russia.

Elektrostal Map

Locate simply the city of Elektrostal through the card, map and satellite image of the city.

Elektrostal Nearby cities and villages

Elektrostal weather.

Weather forecast for the next coming days and current time of Elektrostal.

Elektrostal Sunrise and sunset

Find below the times of sunrise and sunset calculated 7 days to Elektrostal.

Elektrostal Hotel

Our team has selected for you a list of hotel in Elektrostal classified by value for money. Book your hotel room at the best price.

Elektrostal Nearby

Below is a list of activities and point of interest in Elektrostal and its surroundings.

Elektrostal Page

- Information /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#info

- Demography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#demo

- Geography /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#geo

- Distance /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist1

- Map /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#map

- Nearby cities and villages /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#dist2

- Weather /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#weather

- Sunrise and sunset /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#sun

- Hotel /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#hotel

- Nearby /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#around

- Page /Russian-Federation--Moscow-Oblast--Elektrostal#page

- Terms of Use

- Copyright © 2024 DB-City - All rights reserved

- Change Ad Consent Do not sell my data

Current time by city

For example, New York

Current time by country

For example, Japan

Time difference

For example, London

For example, Dubai

Coordinates

For example, Hong Kong

For example, Delhi

For example, Sydney

Geographic coordinates of Elektrostal, Moscow Oblast, Russia

City coordinates

Coordinates of Elektrostal in decimal degrees

Coordinates of elektrostal in degrees and decimal minutes, utm coordinates of elektrostal, geographic coordinate systems.

WGS 84 coordinate reference system is the latest revision of the World Geodetic System, which is used in mapping and navigation, including GPS satellite navigation system (the Global Positioning System).

Geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) define a position on the Earth’s surface. Coordinates are angular units. The canonical form of latitude and longitude representation uses degrees (°), minutes (′), and seconds (″). GPS systems widely use coordinates in degrees and decimal minutes, or in decimal degrees.

Latitude varies from −90° to 90°. The latitude of the Equator is 0°; the latitude of the South Pole is −90°; the latitude of the North Pole is 90°. Positive latitude values correspond to the geographic locations north of the Equator (abbrev. N). Negative latitude values correspond to the geographic locations south of the Equator (abbrev. S).

Longitude is counted from the prime meridian ( IERS Reference Meridian for WGS 84) and varies from −180° to 180°. Positive longitude values correspond to the geographic locations east of the prime meridian (abbrev. E). Negative longitude values correspond to the geographic locations west of the prime meridian (abbrev. W).

UTM or Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system divides the Earth’s surface into 60 longitudinal zones. The coordinates of a location within each zone are defined as a planar coordinate pair related to the intersection of the equator and the zone’s central meridian, and measured in meters.

Elevation above sea level is a measure of a geographic location’s height. We are using the global digital elevation model GTOPO30 .

Elektrostal , Moscow Oblast, Russia

COMMENTS

WANDERER III charges along in the notorious "Furious Fifties" region of the South Atlantic in 2011 en route from South Georgia to Tristan de Cunha. The rugged 30′ Laurent Giles-designed sloop has sailed more than 300,000 miles in her 65 years and is still going strong. ... Eric reflected, "WANDERER III was probably as small a boat as ...

To Wanderer III, a Toast. After 60 years and countless miles, a classic, humble wooden 30-footer has fulfilled the dreams of not one intrepid couple, but two. From Cruising World 's July 2012 issue. Wanderer III runs before a good, strong westerly gale toward remote Tristan da Cunha island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Thies Matzen.

The "Wanderer III", built for Susan and Eric Hiscock, has been travelling the world for seventy years. Our author, who has sailed the prominent yacht since 1982, looks back. From Thies Matzen. Take: an old boat, a remote longitude in the Pacific, three couples. Add: a less connected and consumed world; letters and boats instead of bytes ...

Wanderer III was made famous by Eric Susan Hiscock during two cicumnavigations in the 1950's. In their book, 'Around the World in Wanderer III' the couple set out from Yarmouth, England(1952) and circled the globe by way of the West Indies, the Panama Canal, Tahiti, Samoa, Fiji, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, the Ascension Islands and the Azores, returning home three years later.

Wanderer III, a 30-foot (9.1 m) Laurent Giles sloop, carried the Hiscocks around the world via the tropics at a time when few people were cruising the world for pleasure on small sailboats. The voyage and book accorded them a degree of popular celebrity, and was the first of their three circumnavigations.

TheSailingChannel.TV has restored and transferred to HD the classic circumnavigation sailing film, "Beyond the West Horizon," filmed by Eric & Susan Hiscock ...