What is a Sailboat Jib?

Last Updated by

Daniel Wade

June 15, 2022

A sailboat jib is a triangular headsail located forward of the mast. The jib typically has less sail area than the mainsail.

Typical single-masted sailboats usually have a jib, which is located between the bow and the mast. The jib takes advantage of the forward part of the boat. The jib is not the only kind of headsail, but it is the most common.

Table of contents

Do Sailboats Need a Jib?

Many sailors often wonder if it's even worth hoisting the jib, especially on a windy day. The truth is that you typically don't need the jib to sail, though you're losing up to 50% of your sail area if you don't.

Under typical conditions, most sailors hoist the mainsail and the jib and reef them as necessary. On windy days, you may get on fine with just the mainsail. Whether or not to hoist the jib is entirely up to your judgment.

Trimming the Jib

The trim of the jib is usually controlled using two jib sheets , one on either side of the mast. This makes sense, as it would be hazardous and time-consuming to unwind a single sheet each time you turn, walk along the deck, and wrap it around the other side of the mast.

If you're sailing with the wind to your port side, you'll manipulate the jib using the starboard jib sheet. The opposite also applies when the wind is to your starboard side. Make sure to secure the correct sheet on the winch and free up the opposite sheet.

Can a Sailboat have Multiple Jib Sails?

Yes, sailboats sometimes have multiple jib sails. That said, not all headsails are jibs. Schooners often use two or three headsails. These include the jib, a smaller jib topsail, and sometimes a fore staysail.

The most common kind of American cruising sailboat is the single-mast sloop, which typically employs a single jib. That's why the vast majority of sailboats you see will only have one headsail.

What are Jib Sails Made Of?

Early jib sails were made of organic canvas-like cotton or a mix of organic fibers. Traditional jib sail material usually contains a mix of cotton, hemp, and other fibrous plant material.

Today, synthetic fabrics have largely replaced traditional canvas materials in sailmaking. Synthetic sails are lighter and stronger than their organic counterparts, and they resist water and weather better as well.

Polyester Jib Sails

Modern jib sails are made of a woven blend of polyester and other synthetic material. A material called Dacron is one of the most common sail fabrics due to its low cost, excellent UV resistance, and its tendency not to stretch. Dacron jib sails can be expected to last many years with minimal attention and few failures.

Nylon is another common sail material. Like polyester, nylon is an inexpensive and robust synthetic material that's great for sailmaking. Nylon is extremely lightweight, making it ideal for spinnakers. However, nylon stretches too easily for some applications, and it's prone to damage by some chemicals.

Kevlar Jib Sails

Kevlar is a relatively common sail material. It's considered a 'premium' fabric due to its cost and spectacular qualities. Kevlar has an excellent strength-to-weight ratio and resists stretching better than Nylon or Polyester. Due to its high cost, Kevlar sails are usually only found on racing sailboats and luxury yachts.

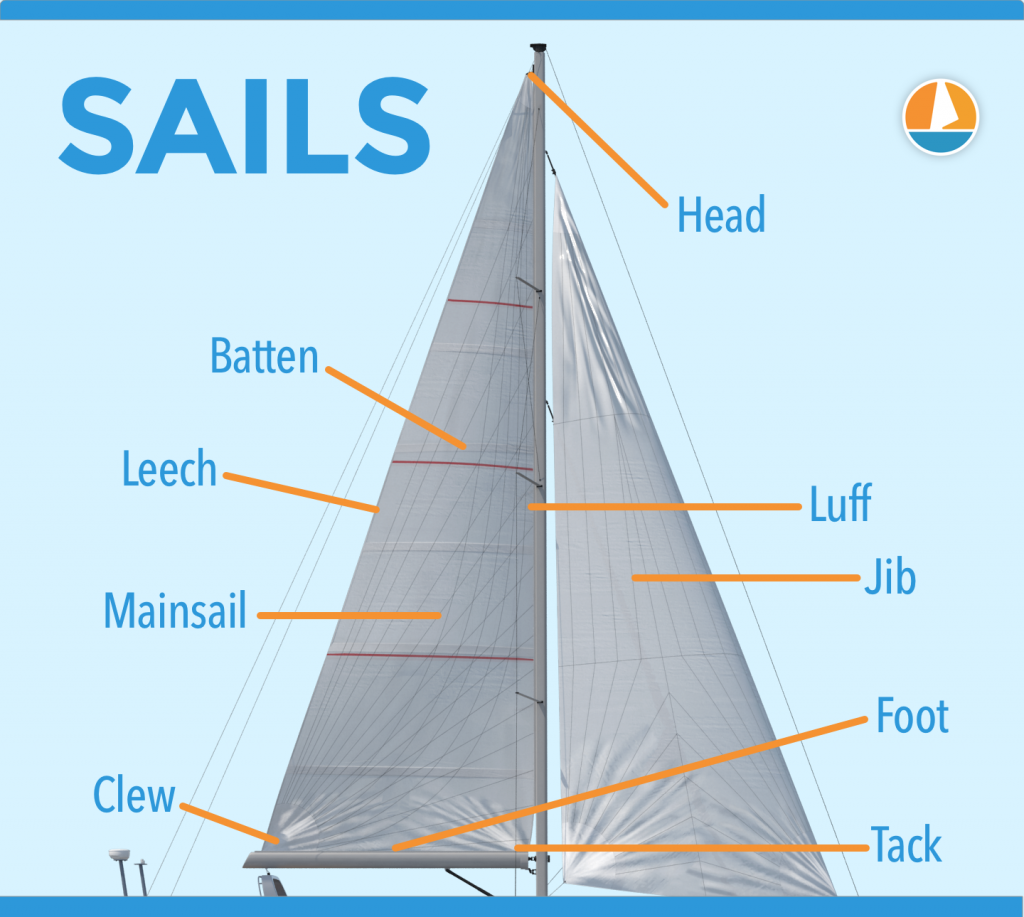

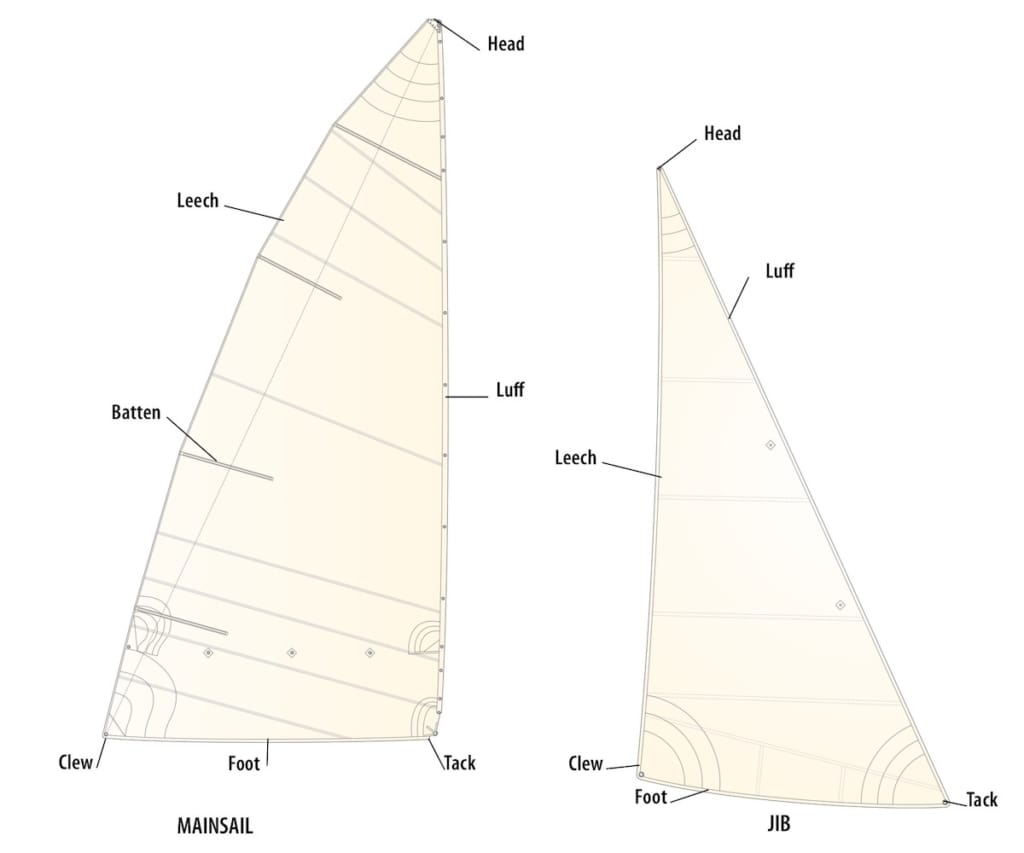

Parts of the Jib

The jib on a sailboat has many parts and mounting points, and it's important to understand where they are, what they do, and what they're called. The parts of the jib are similar to the mainsail, and you'll likely recognize them easily.

The foot is the horizontal section that runs across the base of the sail. It's usually a strip of reinforced sail material which keeps it from fraying. Think of the foot as the bottom of the jib.

The clew is the bottom corner of the jib, and it's located on the aft section of the foot. It usually contains a grommet. Since the jib is a triangular sail, the clew is the corner of its base 90-degree angle.

The leech is the long straight section of the jib that runs parallel with the mast. The leech runs from the clew at the foot of the sail to the very top.

Note that the orientation of the leech on the jib follows the direction of the mainsail and not the shape. In both cases, the leech is located on the aft part of the canvas.

The head of the jib is located at the very top and usually forms the smallest angle of this triangular sail. The head also contains a grommet similar to the clew.

Like the mainsail, the luff is located on the forward part of the jib. The luff is the longest section of the sail, stretching from the tip of the sail to the very bottom and forward end.

The tack is located directly forward of the clew on the opposite (forward) end of the foot. The tack, like the clew and the head, has provisions for rigging.

Traditionally, headsails like the jib are entirely unsupported by spars. However, many sailboat owners opt to install a jib boom to extend their bowsprits or improve off- wind sailing . A jib boom operates much like a traditional mainsail boom.

The jib boom mounts to the forward part of the bowsprit and pivots from its pedestal. A jib boom is useful when projecting the sail, but a spinnaker can typically be used to achieve the same result.

Some sailors caution against the use of jib booms, as they offer few benefits for windward sailing. Additionally, they take up space on the bow and pose the same hazards as a mainsail boom.

Jib vs. Genoa: What's the Difference?

The jib is often confused with the genoa: another common kind of headsail. The jib and the genoa look similar and perform the same function, but the genoa is larger.

A working jib typically makes up less than half of the total sail area, though it's sometimes around the 50% mark. The genoa, on the other hand, is usually equal to or larger than the mainsail.

The Genoa-type headsail is wider than the jib at the base. As a result, it doesn't fit between the tip of the bowsprit and the mast. Genoa sails stretch around the mast and extend far past it. This gives the genoa a distinct oversized look.

Reefing the Jib

Reefing is how you reduce the area of the sail. Reefing is necessary for windy conditions or when reducing speed. Jib reefing is a bit more complicated than mainsail reefing, as the jib doesn't always have a boom.

One way to reef the jib is to wind it around a roller furling starting with the luff. You can also reef the jib vertically using its reefing points and a few pieces of rope.

Roller Furlings

Roller furlings are an increasingly popular way to reef and stow headsails. Roller furling systems work for jibs and genoas and streamline the process significantly.

How a Roller Furling Works

A roller furling begins with a drum mounted at the base of the headstay and a swivel at the top, allowing the whole stay to rotate. The jib feeds through a groove in the headstay, which allows you to wind it up around the stay whenever necessary.

Roller furlings allow you to easily reduce sail area from the cockpit. Simply loosen the sheets and wind the furling using a line, and watch the jib shrink right in front of you. Roller furlings eliminate most haphazard trips across the deck to the bow and eliminate the need to hoist and lower the jib.

Electric Roller Furlings

Today there are numerous electrically-controlled roller furlings available. These devices are almost as easy to install as manual roller furlings, and they offer an additional level of convenience.

Electric roller furlings reduce deck clutter and decrease the labor required to sail your boat. However, electric furling systems are costlier than the majority of manual roller furling.

Related Articles

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Sailboat Parts

Learn About Sailboats

Most Recent

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 13, 2023

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Discover the Magic of Hydrofoil Sailboats

December 11, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Get the best sailing content.

Top Rated Posts

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies. (866) 342-SAIL

© 2024 Life of Sailing Email: [email protected] Address: 11816 Inwood Rd #3024 Dallas, TX 75244 Disclaimer Privacy Policy

No products in the cart.

Sailing Ellidah is supported by our readers. Buying through our links may earn us an affiliate commission at no extra cost to you.

A Full Guide to The Jib Sail And How To Use It

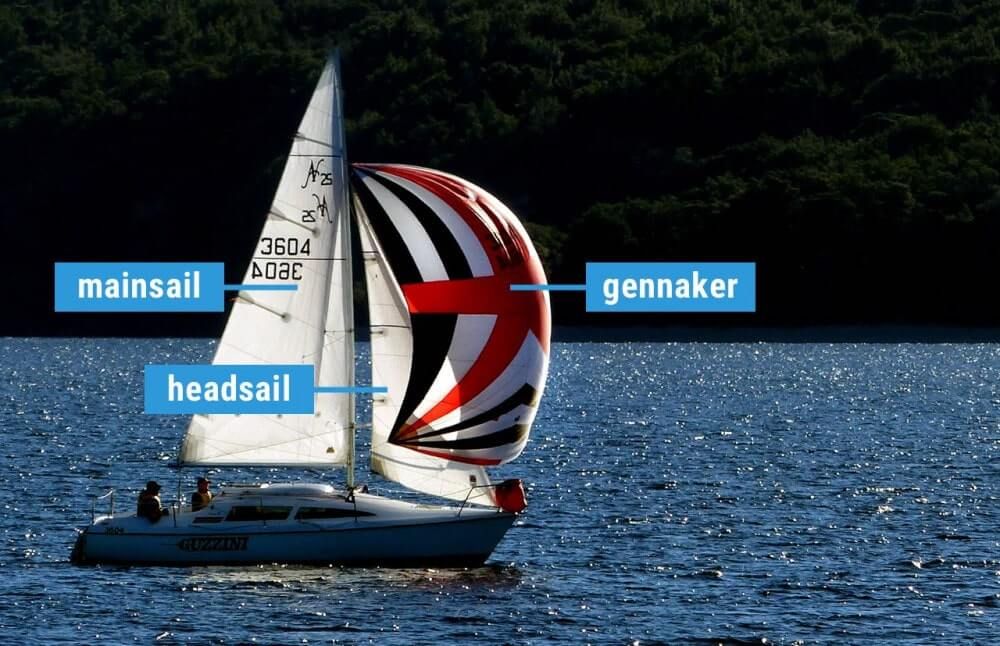

Most cruising boats today have a sail plan consisting of at least three sails: A mainsail, a headsail, and a light-wind sail.

The Jib sail (along with its sister, the Genoa) is one of the most widely used headsails on modern sailboats in combination with a larger mainsail. It is very versatile and easy to use in different configurations throughout most weather conditions.

In this article, I want to explain the Jib in detail and talk a bit about how it works and how we rig and trim it to get the most performance out of the boat. I’ll also show you each part of the sail and its materials before explaining how it differs from other headsails like the Genoa .

Finally, I’ll finish with some tips on maintaining the sail properly to make sure it last as long as possible.

Well, shall we get started?

What is a Jib sail, and what do we use it for?

The Jib is a triangular sail that does not overlap the mainsail. It is typically between 100% and 115% of the foretriangle size and is commonly seen on modern vessels with fractional rigs.

The foretriangle is the triangular area formed by the mast, deck, and forestay. Learn more terms here .

Like other headsails, the Jib is usually rigged on a furling system attached to the forestay , making it easy to operate. The Jib can also be rigged with a self-tacking system, making upwind sailing easy for you, whether you want to cruise solo or with your friends.

How the Jib works on a sailboat

The Jib provides a sail area forward of the mast, allowing the boat to be steered and balanced effectively.

The curved shape of the sail creates a pressure differential. The outer, more convex side (leeward side) has a lower pressure than the inner, concave side (windward side). This pressure differential generates lift, which translates into forward propulsion, much like how an airplane wing produces lift.

How to rig a Jib

You can rig the Jib on either a furling system or directly to the forestay. Most modern sailing boats are equipped with a furling system, which is a long sleeve that runs from the top of the mast down to the bow and attaches to a drum on the bottom and a swivel on the top.

Take a closer look at this step-by-step process on how to rig the Jib to sail onto a furling system:

- Feed the Jib’s luff into the track on the furler’s sleeve with the top of the sail first and connect the head ring on the sail to the chackle on the swivel.

- Attach the Jib halyard to the swivel and hoist the sail up.

- When the sail is hoisted almost all the way to the top, you attach the sail’s tack to a shackle on the top of the drum.

- Put the halyard on a winch and winch it tight.

- Now you have to manually roll up the sail around the forestay and tie on the two sheets to the clew of the sail.

- Lead the two sheets on each side of the vessel’s side decks through the sheet cars, turn blocks, and back to the winches.

- Now that the sail is furled away, we need to tie the furling line onto the drum. You have to figure out how the furling line attaches, as it differs from system to system.

- Once the furler line is attached to the drum, ensure that it can wrap itself up freely.

- Pull the sail back out using one of your sheets and monitor that the furling line wraps on nicely.

- Leed the furling line through the blocks and funnels, through the jammer , and leave it next to the winch.

- Furl the sail away again using the furling line and ensure that the sheets run freely as you monitor your sail getting wrapped nicely around the forestay.

- Secure the furler line jammer and tidy up your two sheets. Make sure to secure the sheets around the winches.

So, you see now why most boats use furling systems? It is easy! Many larger sailboats even have electrical furlers, removing the need for the furling line.

How to use, reef, and trim a Jib

To use the Jib, you wrap the furler line around the winch, open the jammer, and pull on either of the sheets, depending on which tack you are sailing on. You should hold on to the furler line to prevent the sail from unfurling itself uncontrollably, especially in strong winds. Trying to catch it if it starts running can injure your hands, so be careful! I’m speaking from experience here; burned hands are “No bueno.”

You can now unfurl the entire sail or a part of it. Once the full sail, or the amount you desire, is out, adjust your car position and tighten the sheet.

How to reef a jib

You do the opposite as the above to reef the sail or furl it back in.

Ease off the working sheet, but keep it on the winch. At the same time, pull in on the furler line either manually or on the winch. Remember to move the cars forward and re-tighten the sheet if you are reefing away only a part of the Jib.

How to trim a jib

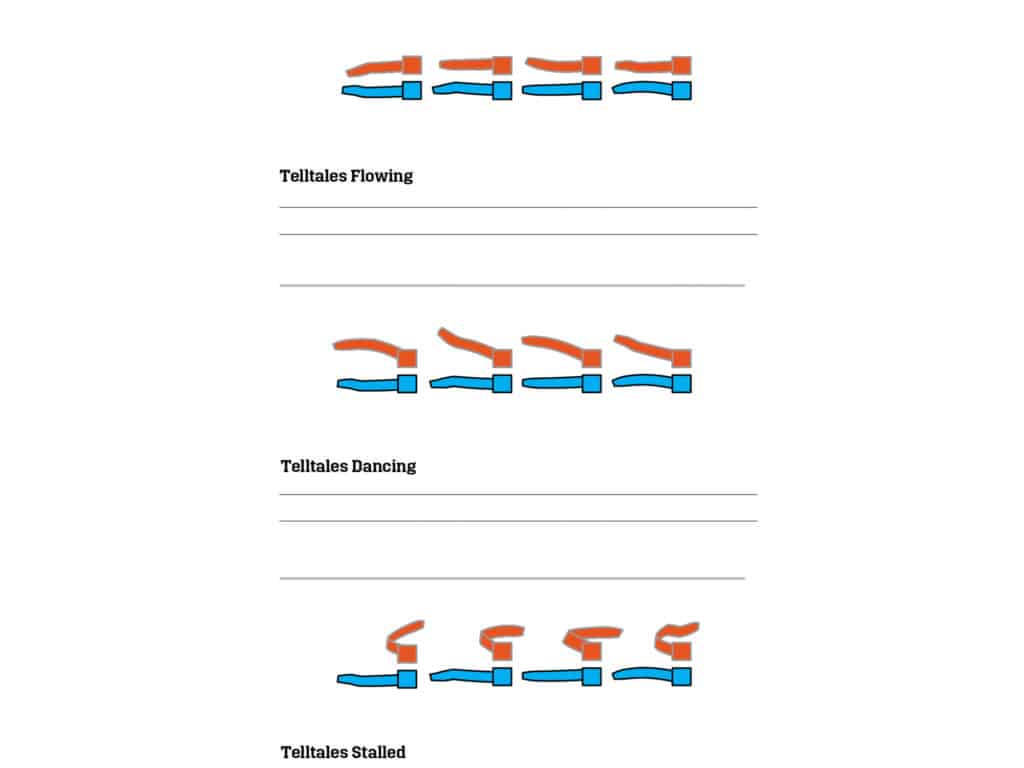

Adjusting the sheet cars and sheet tension is important to obtain an optimal sail shape in the Jib. Finding this balance is what we call sail trim . I’m not going too deep into sail trim here, as it is a topic for itself, which will require a separate article,.

But here is a rule of thumb:

You want the leech and foot of the sail to form an even “U” shape on any point of sail . When sailing upwind, you usually move the car aft. When bearing off the wind, you move the car forward.

The goal is to apply even tension on both the foot and the leech. When you reef the sail, you’ll also want to move the car forward to adjust for the reduced sail area. Sailing downwind doesn’t require the same fine-tuning as upwind sailing.

Four tips for sailing upwind:

- Winch up the jib sheet until the leech stops fluttering and the foot has a nice, even “U” shape.

- You must move the sheet car forward if the foot is tight and the leech flutters.

- Move the sheet cars aft if the leech is tight and the foot flutters .

- If the wind increases and the boat starts to heel excessively, you can either ease off the sheet or adjust your course more head to wind.

You should play around and experiment with sail trim, as every boat behaves differently. Trimming sails is an art that takes time to master. Staysails, Jibs, and Genoas are trimmed the same way, but the car positions will be different due to their size and shape differences. Once you learn how to trim a Jib, you’ll be able to trim any headail and even a storm jib or a spinnaker.

Sailing with more than one Jib

Sailing with multiple jib sails can be beneficial on longer downwind passages. Most furling systems have two tracks, allowing you to have two Jibs on the same furler, making this setup easy to reef. You can do the same with Yankees and Genoas, depending on what you have available in your boat.

Some sailboats have two or more forestays, allowing them to have two individually furled Jibs. This is usually called a cutter rig. Most Cutter rigs, however, use a Staysail on the inner forestay and a Yankee sail on the outer, but this versatile rig allows you to experiment with many setups.

Exploring the different parts of the Jib

Head: The head is the top corner of the Jib. It typically has a ring in the top corner that attaches to the Jib halyard or the top swivel for furling systems.

Leech: The leech is the aft part of the rib, located between the clew and head.

Luff : A Jib’s luff is the front part between the tack and head. Jibs can be equipped with luff foam to help maintain their shape when partially reefed on a furler.

Clew : The clew is the aft lower corner of the jib where the sheets are attached.

Tack : The tack is the lower, forward corner of the Jib. The tack is connected to a furler drum on the forestay on most sailboats. Vessels using traditional hank-on headsails connect the tack to a fixed point on the bow.

Foot : The foot of the Jib is the bottom portion of the sail between the clew and the tack.

Telltales: Telltales are small ropes, bands, or flags attached to the front of the Jib’s leech to help us understand how the wind affects the sail and allow us to fine-tune the trim for optimal performance.

Commonly used materials for the Jib

The most common material used for Jib’s today is Dacron woven polyester, followed by CDX laminate due to the relatively affordable price. Continuing up the range, we find woven hybrids like Hydranet, Vectran, Radian, and other brands.

Then, we have advanced laminates with Aramids, carbon, kevlar, and more exotic materials. At the top of the spectrum, we find the latest technology in DFi membrane sails like Elvstrøms EPEX or North Sails 3Di, which comes at a premium price tag.

These days, however, modern technology has given us warp-oriented woven cloth, which is becoming a popular option due to its increased ability to keep shape over time without stretching as much as traditionally cross-cut dacron sails. ProRadial, made by Contender and Dimension Polyant, is a good example. North Sails has an excellent article that goes in-depth on sail materials.

The difference between a Jib and a Genoa

The difference between a Jib and a Genoa is that the Jib is a headsail that does not overlap the mainsail, while the larger Genoa is designed to overlap the mainsail. While the smaller Jib is excellent at pointing upwind and easier to handle, the larger Genoa excels on any points of sail with the wind behind the beam.

Genoas are usually larger than 115% of the foretriangle , with sizes ranging from 120% to 150%. They are often used on yachts with masthead rigs and smaller mainsails but are also common on fractional rigs.

How to Maintain and Care for Your Jib Sail

Good maintenance and care of your Jib will ensure optimal performance and minimize wear and tear. Check out these tips on how to maintain and protect your Jib:

- Rinse the Jib with fresh water regularly and leave it up to dry before packing it away. Proper drying will prevent moisture and mildew.

- Give the sail a service once a year. Check for any damaged seams and repair them if necessary. If there are any chafing marks, reinforce the sail with patches on chafe points and add shafe guards to the equipment it rubs against.

- Protect the sail from UV rays by keeping it packed away when not in use. A furling Jib can be protected by adding a UV strip to the foot and leech.

I also wrote an article on how to make sails last longer .

Final Words

We have talked a lot about the Jib’s features and how it works in this article. I recommend you to head out and set sail to get some experience and play around with your sails. If you don’t have a boat, chat around in your nearest marina; someone will for sure bring you along for a sail. I know I would.

Remember to experiment with sail trim and practice tacking and maneuvering the vessel with the sail on both the port and starboard sides.

If you still have questions, check out the frequently asked questions section below or drop a comment in the comment field. I’ll be more than happy to answer any of your questions!

PS: Explore more sails in my easy guide to different types of sails here .

FAQ – The Jib Sail Explained

When to use a jib sail.

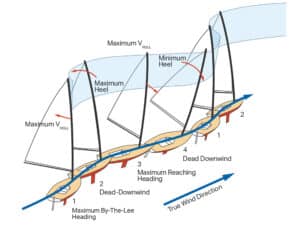

The Jib is an excellent sail for most conditions, especially when cruising at any angle towards the wind. The Jib has a benefit over the Genoa in strong winds as it is easier to handle, and its smaller size makes it more effective than a reefed Genoa when sailing to windward.

Can you sail with just the Jib?

It is possible to sail with just the Jib alone, and it works exceptionally well downwind on deep angles where the mainsail usually would have blocked off the wind.

Can you sail upwind with just the jib?

It is possible to sail upwind with just the Jib, but most sailboat owners prefer to balance their boats by flying their mainsail combined with theiJib when sailing to windward.

What is the difference between a Genoa and a Jib?

The Genoa is different from a Jib sail as it is larger and overlaps the mainsail, whereas the Jib is smaller and does not overlap the mainsail.

Sharing is caring!

Skipper, Electrician and ROV Pilot

Robin is the founder and owner of Sailing Ellidah and has been living on his sailboat since 2019. He is currently on a journey to sail around the world and is passionate about writing his story and helpful content to inspire others who share his interest in sailing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

How To Use a Jib on a Sailboat (Here’s What You Need To Know)

If you’re a sailor looking to maximize your control of your sailboat, learning how to use a jib is essential.

A jib is a triangular sail mounted at the bow of the boat and is a key component in controlling the speed and direction of your boat.

This article will provide an overview of what a jib is and how to use it, including understanding the forestay, adjusting the jib sheet, positioning the jib, trimming the jib, and practicing with a jib.

Plus, we’ll provide a few tips to ensure you get the most out of your jib.

Read on to discover everything you need to know to use a jib on a sailboat.

Table of Contents

Short Answer

A jib is a triangular sail that is set on a stay in front of the mast of a sailboat.

To use a jib, the sheet attached to the clew of the sail must be pulled in to bring the sail around so that the wind fills it.

The sheet should be adjusted to keep the sail trimmed properly while sailing.

The jib can also be used to help turn the boat, by easing the sheet and allowing the sail to swing out to the windward side.

What is a Jib?

A jib is an essential component of a sailboat, as it provides the boat with increased control and maneuverability on the water.

A jib is a triangular sail that is mounted on the front of the boat, also known as the bow.

It is attached to the forestay, a metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

The jib is used to create lift, allowing the sailboat to move more quickly and efficiently through the water.

The jib works in conjunction with the main sail, providing additional power and control when sailing.

It can be adjusted to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat, which can help to increase the speed of the boat and improve its performance in different wind conditions.

Additionally, the jib can also be used to help the boat turn and maneuver in tight spaces, such as when entering a harbor or marina.

In order to use a jib on a sailboat, the jib must first be raised and secured to the forestay.

This is usually done by attaching it to the luff groove, which is a groove along the edge of the sail that slides onto the forestay.

Once the jib is secure, the jib sheet is used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

The jib should be adjusted according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat.

Finally, the jib trim is adjusted, which will keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

With practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib to their advantage.

Understanding the Forestay

When it comes to using a jib on a sailboat, understanding the importance of the forestay is essential.

The forestay is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

It plays an integral role in the efficiency and maneuverability of the boat, as it is the connection point for the jib sail.

Without the forestay, the jib cannot be raised and secured, which limits the boats performance.

Knowing how to properly adjust and maintain the forestay is key to using a jib correctly and efficiently.

When raising the jib, the forestay should be taut to hold the jib in place.

It is essential to make sure that the forestay is not too loose, as it could cause the jib to flutter and lose its shape.

Additionally, the forestay should not be too tight, as it will increase the strain on the jib and could cause damage.

The tension of the forestay should be adjusted to achieve the optimal balance between stability and sail shape.

In addition to ensuring the proper tension of the forestay, it is important to pay attention to the alignment of the forestay with the mast.

If the forestay is misaligned with the mast, it can disrupt the wind flow and cause the jib to flutter.

This fluttering can be prevented by ensuring the forestay is properly aligned.

By understanding the role of the forestay and how to adjust it correctly, sailors can use a jib to their advantage and improve their sailing performance.

With practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib and the forestay to achieve the desired angle and direction of travel.

Adjusting the Jib Sheet

Adjusting the jib sheet is a key part of using a jib on a sailboat.

The jib sheet is a rope or line that is attached to the clew of the jib and runs to the cockpit or winch, allowing the sail to be adjusted to the appropriate position and angle.

It is important to ensure that the jib sheet is securely attached to the clew of the jib before sailing.

Additionally, the jib sheet should be adjusted to the correct tension depending on the wind conditions.

If the jib sheet is too loose, the jib will flog and be ineffective.

If the jib sheet is too tight, the sail will be over-trimmed and the boat will be slower.

To find the optimal jib sheet tension, try different tensions and angles and make sure to pay attention to how the boat responds to the changes.

With practice, you will be able to determine the best tension for the jib sheet.

Positioning the Jib

Positioning the jib on a sailboat is an important step for any sailor looking to make the most of their sailing experience.

While the jib is an essential component of a sailboat, it is also essential to understand how to properly use it.

In order to use a jib, the jib must first be raised and secured to the forestay, which is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

The jib sheet is then used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

It is important to pay attention to the wind direction and adjust the jib accordingly.

The jib should be adjusted to be perpendicular to the wind direction, and this angle should be kept consistent during the sail.

This helps to ensure that the sailboat will move in the desired direction, and that the jib will provide optimal lift.

Sailors should also adjust the jib trim, which is the tension on the jib sheet.

The jib trim should be adjusted according to the wind conditions to keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

Too much tension on the jib sheet can cause the jib to backwind, which can slow down the boat and make it difficult to maneuver.

Too little tension can cause the jib to luff, which can reduce the lift provided by the sail.

Finally, with practice, sailors can become proficient in using a jib to their advantage.

Utilizing the jib to its fullest potential can help to optimize speed and control, and make the sailing experience even more enjoyable.

Trimming the Jib

Trimming the jib is a crucial part of using a jib on a sailboat.

This is the step that will ensure the jib is in the optimal position for the best sailing experience.

The jib trim should be adjusted according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the boat.

When the wind is coming from a certain direction, the jib will need to be adjusted accordingly.

If the wind is coming from the starboard side, the jib should be adjusted to the right.

If the wind is coming from the port side, the jib should be adjusted to the left.

In addition to adjusting the jib to the wind direction, the jib trim should also be adjusted to the desired angle of the boat.

This will help to maximize the performance of the boat and ensure that the jib is in the best position for sailing.

The jib trim should be adjusted so that the angle of the jib is roughly the same as the angle of the boat.

This will ensure that the jib is properly positioned and will help to maximize the performance of the boat.

Finally, the jib trim should be adjusted periodically to ensure that the jib is in the best position for sailing.

This can be done by observing the jib and adjusting the trim as necessary.

By trimming the jib correctly, sailors can improve their sailing experience and make the boat faster and easier to navigate.

Practicing with a Jib

Using a jib on a sailboat requires practice and skill to become proficient.

While learning the basics of how to use a jib is important, it is also necessary to gain an understanding of the wind and how it affects the sailboat.

By learning the basics of how a jib works and how to adjust it, sailors will be able to use the wind to their advantage.

The jib should be raised and secured to the forestay, which is the metal cable that runs from the bow of the boat to the mast.

Next, the jib sheet is used to control the jibs angle and direction of travel.

This is done by adjusting the tension on the sheet, which will affect the angle of the sail and the direction of the boat.

The jib trim is then adjusted to keep the jib in the optimal position for smooth sailing.

To practice using a jib on a sailboat, it is important to start slowly and focus on learning the basics.

Begin by familiarizing yourself with the wind and understanding how the direction of the wind affects the sailboat.

Once you understand the basics, you can experiment with different angles and settings to see how the jib affects the boats speed and direction.

As you become more comfortable and experienced with using a jib, you can begin to practice more advanced maneuvers, such as tacking, jibing, and reefing.

These maneuvers can be used to control the speed and direction of the sailboat, and can make the sailing experience more enjoyable.

Sailing with a jib can help to make the boat faster and easier to navigate, and can enhance the sailing experience.

By understanding the basics of using a jib and practicing regularly, sailors can become comfortable and confident in their ability to use a jib to their advantage.

Tips for Using a Jib

Using a jib on a sailboat is a great way to increase control and maneuverability while sailing.

A jib is essentially an additional sail that can be attached to the forestay, a metal cable running from the bow of the boat to the mast.

It is important to know the basics of how to use a jib in order to maximize the sailing experience.

Here are some tips to help you get started.

First, it is important to ensure that the jib is properly raised and secured to the forestay.

This can be done by attaching the jib’s clew, or the corner of the sail, to the forestay using a wire or cable.

It is also important to make sure that the jib is taut and free of wrinkles or creases.

Once the jib is in place, the jib sheet can be used to control the jib’s angle and direction of travel.

This is done by adjusting the jib sheet, which is a rope connected to the corner of the jib, in order to change the tension of the sail.

It is important to adjust the jib sheet according to the wind direction and the desired angle of the sailboat.

This will ensure that the jib is in the optimal position to take advantage of the wind.

Finally, the jib trim should be adjusted.

This is done by using the jib sheet and the jib halyard, which is a rope that runs from the top of the jib to the deck.

By adjusting the tension of the jib halyard, the angle of the jib can be changed to keep it in the best position for sailing.

Using a jib correctly can help to improve the sailing experience and make the boat faster and easier to navigate.

By following the tips outlined above, sailors can get a better understanding of how to use a jib on a sailboat and maximize their sailing experience.

Final Thoughts

Using a jib on a sailboat can make sailing smoother, faster, and more enjoyable.

With a solid understanding of the components and the proper technique, anyone can become a pro at using a jib.

It just takes a little practice, patience, and understanding of the wind direction.

With the right know-how, you’ll be sailing like an expert in no time!

James Frami

At the age of 15, he and four other friends from his neighborhood constructed their first boat. He has been sailing for almost 30 years and has a wealth of knowledge that he wants to share with others.

Recent Posts

When Was Banana Boat Song Released? (HISTORICAL INSIGHTS)

The "Banana Boat Song" was released in 1956 by Harry Belafonte. This calypso-style song, also known as "Day-O," became a huge hit and remains popular to this day for its catchy tune and upbeat...

How to Make Banana Boat Smoothie King? (DELICIOUS RECIPE REVEALED)

To make a Banana Boat Smoothie King smoothie at home, start by gathering the ingredients: a ripe banana, peanut butter, chocolate protein powder, almond milk, and ice. Blend the banana, a scoop of...

Better Sailing

Jib Vs Genoa: What is the Difference?

Most modern sailboats don’t need big overlapping headsails to ensure performance when sailing upwind. In the old days, sailboats were really heavy, their keels were long, and the sail area was the most crucial part that made the boat moving. However, nowadays light masts and rigging are available and facilitate many things while sailing. For example, if you increase the mast’s height and apply a high-aspect sail plan with a jib that overlaps no more than 105%, well this is quite an efficient rigging. So, are you are thinking of going offshore and wondering what sails are the best for your sailboat? Do you want to clarify the difference between a jib and a genoa? Then, follow me and keep reading!

Description of a Genoa

The main characteristics of a genoa are its shape and size. Genoas go past the mast, are triangular, and tend to overlap the mainsail, to some extent. It’s also one of the many headsails that can be set on a Bermudian rig. The numbers 130,150 etc refer to a percentage that has to do about the relationship of the length of the foot of the genoa and from the forestay to the front of the mast. As a result of this operation, i.e. the Luff Perpendicular divided by J (the distance), you get the overlap percentage of the sail.

Keep in mind that the larger the number you get the larger the sail would be. In general, in order to measure genoas, we often use the length of their Luff Perpendicular. In order to construct the LP, you can draw a line from the sail’s clew to the luff, and carefully intersect the luff at the right angle.

Description of a Jib

The Jib is also a triangular sail that increases sail area and improves handling. Therefore, it increases the sailboat’s speed. Basically, the mainsail controls the stern of the ship whereas the headsail, which sits forward the mast, is most of the time a jib. One of the main functions of the Jib is that it funnels the airflow along the front of the mainsail. This improves the airflow. Moreover, the jib gives control over the bow of the boat, thus making it easier to maneuver the boat. There are different sizes for a jib with the smallest being a storm jib.

In case the boat has a furler, then the size of the genoa or jib can be adjusted according to the wind’s strength, direction, and speed. Usually, jibs are 100% to 115% LP and are used in areas with strong winds. Also, a jib won’t be longer than 115% LP of the fore-triangle dimensions. Lastly, to ensure better performance in high wind speed the smaller area of the jib the better.

>>Also Read: Names of Sails on a Sailboat

Genoa VS Jibs – What Is The Difference Between Them?

Generally, Jibs and Genoas are triangular sails that are attached to a stay in front of the mast. Jibs and genoas are employed in tandem with the mainsail in order to stabilize the sailboat. They usually run from the head of the foremast to the bowsprit. A genoa is like a jib but is larger and reaches past the mast. But, as aforementioned, when the jib overlaps the mast we refer to it as a genoa. Also, a genoa overlaps the mainsail to some degree. Both sails are measured by their Luff Perpendicular percentage, i.e. the area within the fore-triangle that they use. Sometimes, there are large genoas that cover the majority of the mainsail. This mainly happens in light wind conditions where the most sail area is used to increase performance.

And again, when the headsail doesn’t overlap the mast is considered a jib. On the other hand, an overlapping sail is a genoa. Generally, smaller jibs are more lightweight, less expensive, and easy to handle. Jibs might also have a better lifespan as their leeches aren’t dragged across the mast, shrouds, and spreaders. So, all these characteristics make the jibs easier to trim and change. Furthermore, as they weigh less they will heel and pitch less. Lastly, keep in mind that there are different sailcloths weights, and materials that can be used on jibs and genoas. The sail design of each sail is always based on the type of sailboat and the sailing conditions will determine the sailcloth’s weight.

Having Multiple or Less Sails on your Sailboat

In case your sailboat has a larger genoa then you ought to think about getting a smaller headsail. For example, a sail with an LP of around 115% or maybe less. You can use the smaller sail when the wind is getting stronger and keep your genoa in storage. It’s essential to store, protect, and generally take care of your sails a few times per year. So, it’s recommended to often change your sails once in a while. Remember that for every boat has its own sail plan. For example, a boat might need one, two sails, three, etc that will enhance its performance. Each one used for different weather conditions and for different sailing plans.

The rule of thumb says that the fewer the sails less the drag will be. Meaning that you can sail higher to the wind with a single sail rather than having multiple sails of the same aspect ratio and total area. Furthermore, for the same total sail area and same geometrical shape, having multiple sails means that they’ll be less tall. In other words, they’ll catch slower wind closer to the ground. However, for the same total sail area, multiple sails will provide less heeling. This means that you can have lighter structures that support them.

Sail Area and Furling

In the old times, boats used to have long and shallow keels therefore it was crucial to fly a significant amount of sail in order to produce horsepower. But, when a vessel has a light material construction, light masts, and rigging then the height of the mast can be taller without having an effect on the righting moment. So, an overlapping jib, around 115%, results in more efficiency and less dependence on the additional overlap. But, when furling away sail shape from a large genoa you might reduce the sail’s shape efficiency. This is because when using a genoa for strong winds, it’s going to gradually cause an uneven stretch to the Dacron.

Remember that not all sails suit for all kinds of boats. Some boat owners might recommend a specific sail for a specific vessel. But the most important factors that determine what sails suit your boat are the location in which you sail, the type of the vessel, and the captain’s experience. For example, a sail made for Oceanis 331 in Florida will be completely different than a sail made for the same boat that sails in the Meditteranean.

But, what is the best sail size for cruising boats? A 130 or 135% headsail is great because this sail shape is flat thus can be reefed efficiently. However, a 130% headsail doesn’t have a good sheeting angle but is great for offshore sailing. On the other hand, non-overlapping headsails have a narrow sheeting angle so they’re not appropriate for offshore sailing.

In general, light-air sails are large sails and need adequate camber depth to work in light winds. So, when rolling them up and use them reefed you can’t take in enough of the camber to make the sail work windward. And that’s why there are several roller-furling headsails that include lengths of rope or a strip of dense foam that runs along the luff of the sail from the head to the tack.

Apart from that, any sailboat traveling offshore is going to need a small 130% headsail in order to withstand harsh weather conditions. It’s always better to use more than one headsail when voyaging overseas. Last but not least, don’t forget to take into consideration the trade-offs when sailing upwind.

Improve your Sailboat’s Performance

As aforementioned, remember that the most crucial factors that determine the right sail size for your sailboat are the type of your vessel and the kind of passage you’re planning. There are certain things that you can do to improve your sails’ performance, no matter the kind of headsail you have. The first one refers to adding a means of adjusting the sheeting position when reefing and unreefing the headsail. For instance, you can add a block-and-tackle system that can pull the genoa lead forward when the sail is reefed. And when unreefed you can ease it aft. Generally, when moving a lead forward or aft, this changes the angle at which the sheet pulls down on the clew. And when pulling the clew down it trims the top of the jib, but when moving it aft it opens the top of the jib.

The Bottom Line

Modern technology and sail engineering have improved the development of sailcloths, sails’ versatility, and design tools to enhance their performance. Nowadays, you can choose between different types of sails according to the type of your sailboat, location, and experience. So, what’s the difference between a jib and a genoa? In order to clarify the main difference between a jib and genoa you should bear this in mind: When the foot of the headsail is longer than the distance from the forestay to the mast then we refer to a Genoa. Otherwise, the headsail is called a Jib. Basically, a genoa is a large jib that reaches past the mast and overlaps the mainsail. I hope that by reading this article you made clear the difference between a jib and a genoa and how you can enhance your sails’ performance. Wish you a lot of adventurous voyages to come!

Peter is the editor of Better Sailing. He has sailed for countless hours and has maintained his own boats and sailboats for years. After years of trial and error, he decided to start this website to share the knowledge.

Related Posts

Lagoon Catamaran Review: Are Lagoon Catamarans Good?

Best Inboard Boat Engine Brands

Are O’Day Sailboats Good? A Closer Look at a Classic Brand

Why Do Sailboats Lean?

- Buyer's Guide

- Destinations

- Maintenance

- Sailing Info

Hit enter to search or ESC to close.

Learn How To Jibe a Sailboat – Essential Techniques & Tips

Alex Morgan

Jibing, also known as gybing, is a fundamental skill in sailing that every sailor must learn. It involves changing the direction of a sailboat by bringing the stern of the boat through the wind. Proper jibing technique is essential for a safe and smooth maneuver, ensuring the boat maintains control and speed throughout the process.

Understanding the basics of jibing is crucial before attempting the maneuver. This includes comprehending how the wind affects the sails and how to adjust them for a successful jibe. Jibing incorrectly can lead to accidents, damage to the boat, or even capsize.

In this article, we will provide a step-by-step guide on how to jibe a sailboat, covering everything from preparation and communication to the proper handling of the sails and steering. We will also highlight common mistakes to avoid during the maneuver, such as failing to communicate or mishandling the mainsail.

To help improve your jibing skills, we will share some useful tips and techniques for a successful jibe, including maintaining control and speed during the maneuver. With practice and the right approach, you can become proficient in jibing and enjoy the exhilaration of navigating your sailboat with ease.

Stay tuned for the following sections, where we will dive deeper into the details of jibing a sailboat and provide valuable insights to enhance your sailing experience.

Key takeaway:

- Proper jibing technique is crucial: Understanding the basics of jibing and executing it correctly is essential for safe and efficient sailboat handling.

- Step-by-step guide for successful jibing: Following a systematic approach that includes preparation, communication, sail trimming, and balancing the boat is key to executing a smooth jibe.

- Avoid common mistakes: Failing to communicate, allowing the jib to backwind, mishandling the mainsail, and oversteering or understeering are common mistakes to be avoided during the jibing process.

What is Jibing?

Jibing , a crucial maneuver in the world of sailboats, is an art that requires precision and skill. In this section, we’ll unravel the essence of jibing by diving into the basics. Get ready to grasp the fundamental concepts and techniques behind this maneuver, and discover how it can enhance your sailing experience. So buckle up and prepare to explore the intricacies of jibing like never before!

Understanding the Basics of Jibing

Understanding the basics of jibing is important for sailboat enthusiasts. Here is a step-by-step guide to help you grasp the fundamentals:

1. Prepare yourself and the boat for the jibing maneuver. Ensure you have enough space and the necessary equipment.

2. Communicate with your crew members or passengers about the upcoming jibing maneuver. Clear and concise instructions are vital for a successful jibe .

3. Ease the jib sheet gradually, allowing the sail to luff and depower. This step ensures a smooth transition during the jibe .

4. Shift the mainsail by releasing the mainsheet while pulling in the new leeward sheet. This action helps the sail move smoothly to the opposite side.

5. Steer and change course smoothly to initiate the jibe . Maintain control of the boat and be aware of the wind direction and potential obstacles.

6. Trim the jib by pulling in the new leeward sheet to fill the sail with wind on the new course.

7. Stabilize and balance the boat after completing the jibe . Adjust the sails and the boat’s position as needed to maintain control and optimize speed.

Understanding these steps will enhance your jibing skills and contribute to a safe sailing experience. Practice and experience are important in mastering the art of jibing . Always prioritize safety and communicate effectively with your crew for a successful jibe .

The Importance of Proper Jibing Technique

Proper jibing technique is of utmost importance for sailboat maneuvering. It is crucial for ensuring smooth transitions when changing direction. The significance lies in control , accident prevention , and speed optimization . To effectively execute a successful jibe, follow these steps:

1. Prepare the crew: Communication is key to ensure that everyone is ready and fully aware of their responsibilities for the maneuver.

2. Trim the sails: Adjust the settings to optimize power and maintain balance for optimal performance.

3. Steer gradually: Turn the boat slowly and smoothly, allowing the sails to naturally transition to the opposite side.

4. Coordinate the crew: Work together in a synchronized manner to smoothly move the sails across the boat, avoiding any obstructions or tangling.

5. Complete the turn: Once the jibe is done, steady the boat’s course and make any necessary adjustments to maintain control.

Practicing and refining proper jibing technique can significantly enhance sailing proficiency and ensure safety on the water.

Fact: A well-executed jibe has the potential to improve a sailboat’s speed by approximately 10-15% due to better wind exposure on the new tack.

Why is it Important to Jibe Correctly?

Jibing a sailboat correctly is important for the safety of the crew and boat control. By jibing correctly , you prevent accidents, protect sails and rigging, maintain control, preserve boat speed, and improve performance .

Jibing incorrectly can cause accidents like forceful gybing or losing control of the boat, leading to sail and rigging damage. Correct jibing reduces strain on sails and rigging, preventing tears or breakages. Proper jibing allows smooth direction changes, avoiding sudden movements that disrupt balance.

Furthermore, correct jibing maintains momentum and prevents unnecessary loss of speed. Ultimately, proper jibing enhances overall efficiency and navigation success. So, why is it important to jibe correctly ? Because it ensures the safety of the crew, prevents accidents, preserves the condition of sails and rigging, maintains control, preserves boat speed, and enhances performance.

Step-by-Step Guide on How to Jibe a Sailboat

Get ready to set sail with our step-by-step guide on how to jibe a sailboat! We’ll walk you through the process, starting with the crucial preparations and communication. Then, we’ll show you how to smoothly ease the jib sheet and shift the mainsail . As we change course, we’ll also cover steering techniques and the importance of trimming the jib . Don’t forget the final steps of stabilizing the boat and finding that perfect balance. Get ready to master the art of jibing and take your sailing skills to new heights!

Step 1: Preparation

The first step in jibing a sailboat is Preparation . Proper preparation is necessary for a smooth and successful maneuver. Here are the steps to follow:

– Check the wind direction : Assess the wind direction to determine the appropriate course of action and ensure safety.

– Secure loose items : Properly secure all loose items on the boat, including equipment, personal belongings, and anything that could cause damage or injury during the jibing process.

– Inform the crew : Communicate with the crew members and inform them about the upcoming maneuver. Everyone should be aware of their roles and responsibilities during the jibe.

– Prepare the sails : Get the jib and mainsail ready for the jibe by adjusting the tension in the sheets and the angle of the sails.

– Check the surroundings : Look around the boat to make sure there are no obstacles or other vessels nearby that could pose a risk during the jibe.

– Position the helm : Turn the helm in the direction of the intended jibe for a smooth turn and to maintain control of the boat.

– Communicate with the crew : Before starting the jibe, talk to the crew members to ensure they are ready and understand the plan. Clear communication is essential for a successful jibe.

By following these steps, you can prepare yourself properly for a jibe and improve the chances of a safe and controlled maneuver.

Step 2: Communication

Step 2: Communication is crucial for jibing a sailboat and ensuring safety and coordination. Follow these steps:

1. Establish clear communication lines between the helmsman and crew members.

2. The helmsman should give clear and concise instructions using simple commands.

3. Before starting the jibing maneuver, the helmsman should inform the crew members about the upcoming maneuver and its direction.

4. Ensure all crew members acknowledge and understand the helmsman’s instructions.

5. Maintain continuous communication throughout the jibing process to update the crew members about any changes or adjustments.

Effective communication during jibing helps prevent accidents, minimizes confusion, and ensures smooth execution of the maneuver by the entire team.

Step 3: Easing the Jib Sheet

To properly ease the jib sheet during a sailboat jibe, follow these steps:

1. Prepare for the jibe by ensuring all crew members are aware and in their positions.

2. Communicate with the crew about the upcoming jibe for safety and coordination.

3. Slowly and smoothly ease the jib sheet by gradually releasing tension, allowing the sail to luff slightly. The amount you ease the sheet depends on wind conditions and the degree of the jibe. This step is crucial in maintaining control and stability during the maneuver.

4. Monitor the position of the jib as you ease the sheet. It should gently backwind during the jibe to stabilize the boat and facilitate the turn.

5. Steer the boat smoothly during the turn, making sure the jib does not cross the boat too quickly.

6. After completing the jibe , trim the jib sheet in the new position to regain power and control.

7. Maintain stability and balance by adjusting other controls such as the mainsail and the centerboard or keel.

To ensure successful jibes and skillful handling of the sailboat:

– Practice these techniques regularly.

– Maintain clear communication with the crew.

– Adapt to the specific wind and water conditions while sailing.

Step 4: Shifting the Mainsail

- Shift the mainsail by releasing it from its current position and preparing to move it to the opposite side of the boat.

- Ensure that the crew is aware of the maneuver and ready to handle the mainsail.

- Gradually ease out the mainsheet as the wind fills on the opposite side.

- Guide the mainsail smoothly across the boat using your body weight and strength. Avoid letting it swing uncontrollably to prevent accidents or sail damage.

- Maintain control by gradually trimming the mainsheet on the new side as the mainsail crosses over.

- Ensure that the mainsail is properly trimmed and adjusted to the new wind angle for balance and optimal performance.

- Monitor the sail shape and make any necessary adjustments to optimize its position.

To successfully shift the mainsail during a jibe , effective communication , controlled handling of the mainsheet, and gradual adjustments for stability are crucial. Mistakes in this step can result in loss of control or sail damage, so it is essential to practice and develop the necessary skills for a smooth mainsail shift during jibing.

Step 5: Steering and Changing Course

Steering and changing course is crucial for jibing a sailboat, requiring coordination and precision.

1. Shift the mainsail and smoothly steer the boat towards the new course by turning the tiller or wheel.

2. Avoid sudden or jerky movements to prevent destabilizing the boat or losing power in the sails.

3. Monitor the wind direction and adjust steering to maintain proper angle and sail trim for a smooth transition.

4. Be aware of other boats or obstacles nearby and make necessary course adjustments to avoid collision.

5. Control the boat’s speed during the course change by adjusting sail trim and steering to prevent excessive acceleration or deceleration.

6. Communicate any necessary adjustments to the crew, especially those responsible for trimming the sails or handling other tasks.

7. Once the course change is complete, ensure the boat is balanced and stable, checking sail trim, weight distribution, and making any necessary corrections.

Proper steering and changing course during jibing will maintain control and ensure a safe and efficient maneuver.

Step 6: Trimming the Jib

To properly trim the jib , follow these instructions:

Step 1: Position yourself on the windward side of the boat, near the jib sheet .

Step 2: Loosen the jib sheet slightly to allow the jib to luff in the wind.

Step 3: Slowly trim or pull in the jib sheet to bring the jib back to a full position, ensuring a smooth, wrinkle-free sail.

Step 4: Pay attention to the telltales on the jib, which are small pieces of fabric or yarn attached to the sail. They should flow smoothly, indicating proper trim.

Step 5: Adjust the jib sheet tension as necessary to maintain the correct sail shape and control the power in the jib.

Step 6: Continuously monitor the jib’s performance and make small adjustments to optimize speed and efficiency.

Step 7: Coordinate with the helmsperson to ensure proper communication between jib trim and boat steering.

Properly trimming the jib is essential for control, speed, and minimizing heeling while sailing. It helps balance forces, maximize power, and prevent excessive leaning. By following these steps, you can ensure optimal performance during a sailboat jibe.

Step 7: Stabilizing and Balancing the Boat

To stabilize and balance the boat during a jibe, follow these steps:

Step 1: Gradually release the jib sheet as you complete the jibe to allow the sail to swing smoothly to the new side.

Step 2: Maintain control of the boat and prevent oversteering or understeering by keeping a firm grip on the tiller or steering wheel.

Step 3: Adjust the angle of the mainsail to the new wind direction by pulling in or letting out the mainsheet.

Step 4: Ensure proper trim of both the jib and mainsail to maintain balance. The sails should be neither too loose nor too tight.

Step 5: Monitor the boat’s tilt or heel. If it leans too much to one side, adjust the sails or shift weight to restore balance.

Step 6: Make small steering adjustments to keep a stable course, avoiding overcorrection or sudden movements.

Step 7: Continuously monitor the boat’s stability and balance during the jibe, making any necessary adjustments to ensure smooth sailing.

By following these steps, you can safely and enjoyably stabilize and balance the boat during a jibe.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Jibing

When it comes to jibing a sailboat, there are some common mistakes you’ll want to steer clear of. From miscommunication to mishandling the mainsail, these blunders can throw off your course and impact your sailing experience. In this section, we’ll explore four key areas where errors often occur: failing to communicate effectively, allowing the jib to backwind, mishandling the mainsail, and oversteering or understeering. Get ready to navigate these challenges and set sail smoothly towards successful jibing!

1. Failing to Communicate

Failing to communicate can be a crucial mistake when it comes to jibing a sailboat. Proper communication is essential to ensure a smooth and safe maneuver.

To avoid this mistake, it is important to follow these guidelines:

Provide clear instructions: Before jibing, communicate your intentions and provide specific instructions to your crew.

Coordinate timing: Make sure to coordinate with your crew so that everyone is ready to shift their weight and adjust the sails at the right moment.

Stay alert: Keep the lines of communication open and stay aware of any potential obstacles or changes in wind conditions.

Use clear signals: In addition to verbal communication, utilize hand signals or established cues to convey important information.

Remember, effective communication is key for a safe jibing maneuver, fosters teamwork among the crew, and enhances the overall sailing experience.

2. Allowing the Jib to Backwind

To avoid the common mistake of allowing the jib to backwind while jibing a sailboat, follow these steps:

- Prepare for the jibe by ensuring everyone on the boat is aware and ready.

- Communicate clearly with your crew, using hand signals or verbal commands to indicate the upcoming maneuver.

- Ease the jib sheet gradually to prevent catching wind on the wrong side. Release the jib sheet as you steer the boat through the jibe.

- Smoothly shift the mainsail and ensure it is properly controlled and adjusted for the new direction.

- Steer the boat through the jibe , maintaining control and a steady course.

- Trim the jib after completing the jibe to ensure it is properly set and catching wind on the correct side.

- Balance and stabilize the boat by adjusting the sails and controlling the helm to optimize performance.

To prevent backwinding the jib , release the jib sheet gradually and maintain control throughout the maneuver. By following these steps, you can improve your jibing technique and avoid backwinding the jib.

Remember to practice these steps regularly to enhance your jibing skills, maintain control, and speed while sailing. Implementing these techniques will help you navigate smoothly and effectively on the water.

3. Mishandling the Mainsail

Mishandling the Mainsail:

To avoid mishandling the mainsail during a jibe , it is important to follow a few key steps. First, release tension on the mainsheet gradually before starting the jibe. This will help to ease the mainsail and prepare it for the maneuver. Next, carefully cross the boom to the other side of the boat while steering. This should be done with caution to avoid any damage or mishaps. Once on the other side, use the mainsheet to trim the sail and maintain proper shape and control. This will ensure that the mainsail is functioning correctly throughout the jibe. Timing is crucial when performing a jibe. It is important to choose a stable time with enough wind to smoothly complete the maneuver.

To improve your skills in sailboat handling and avoid mishandling the mainsail, consider the following suggestions. First, take sailing lessons or courses to learn proper techniques. This will provide you with a solid foundation of knowledge and skills. Next, practice jibing in different conditions to understand how the mainsail responds. This will help you anticipate any challenges or adjustments that may need to be made. Communication with your crew or sailing partners is also important for smooth coordination. Make sure to communicate your intentions and work together to execute the jibe effectively. Understanding wind conditions and their impact on the mainsail is crucial. Pay attention to the wind direction and strength, and make adjustments to the mainsail as needed. Be vigilant and observant while handling the mainsail. Continuously monitor its performance and make any necessary adjustments or corrections.

By following these steps and suggestions, you can avoid mishandling the mainsail during a jibe and sail safely and effectively.

4. Oversteering or Understeering

When jibing a sailboat, it is important to ensure that you do not oversteer or understeer in order to maintain control and balance. To prevent these mistakes, here are some helpful tips:

1. Maintain a steady helm: To prevent oversteering, avoid making excessive steering inputs during the jibe. Keep the tiller or wheel steady to maintain control.

2. Ease the mainsail gradually: When shifting the mainsail during the jibe, make sure to release it gradually. Avoid releasing it too quickly, as this can cause the boat to jerk or lose balance.

3. Coordinate with crew members: Communication is key during a jibe. Coordinate with your crew members to ensure everyone is prepared and knows what to expect. This will help avoid sudden movements that can lead to oversteering or understeering.

4. Anticipate the turn: Before initiating the jibe, anticipate the boat’s turn and plan your actions accordingly. This will help you avoid making abrupt steering adjustments during the maneuver.

5. Practice proper weight distribution: Maintaining a balanced weight distribution on the boat is crucial. Shift your weight smoothly and evenly to prevent the boat from leaning excessively.

6. Monitor the sails: Keep a close eye on the jib and mainsail throughout the jibe. Adjust the trim as necessary to maintain proper sail shape and prevent oversteering or understeering.

By following these tips, you can avoid the common mistake of oversteering or understeering while jibing a sailboat, ensuring a smoother and more controlled maneuver.

Tips and Techniques for Successful Jibing

Jibing , a crucial maneuver in sailboating, requires skill, control, and finesse. In this section, we’ll dive into the tips and techniques that can enhance your jibing abilities. From improving your jibing skills to mastering techniques for maintaining control and speed, each sub-section will provide valuable insights to help you navigate the waters with confidence and precision . So, get ready to set your sails and embark on a journey to become a master of the jibe !

Tips for Improving Jibing Skills

Here are some useful tips for improving jibing skills:

- Practice sail trim: To maintain control and prevent luffing or overloading, ensure proper trimming of the jib and mainsail before jibing.

- Anticipate wind changes: Effectively plan and execute smooth jibes by paying attention to shifts in wind direction and strength.

- Maintain boat speed: Smooth transitions during jibing require sufficient boat speed. Avoid slowing down too much to stay in control.

- Focus on body position: Proper body position is crucial for successful jibing. Keep balanced and centered in the boat, ready to adjust quickly as the boat changes direction.

Remember, the key to becoming confident and proficient in executing successful jibes is practice and refining your technique.

Fun Fact: Jibing is a maneuver used to change the direction of a sailboat when sailing downwind, involving crossing the stern of the boat through the wind from the opposite side.

Techniques to Maintain Control and Speed

To successfully maintain control and speed while jibing a sailboat, you can follow the following techniques:

1. Preparation is key: It is important to anticipate wind shifts and currents in order to choose the best possible moment for the maneuver.

2. Effective communication: Make sure to inform your crew members about the upcoming jibe, and ensure that everyone is ready to perform their respective tasks.

3. Gradually ease the tension on the jib sheet: By releasing tension gradually, you allow the sail to move smoothly and effortlessly.

4. Swiftly shift the mainsail: Move the mainsail to the opposite side of the boat to maintain balance during the maneuver.

5. Skillfully steer and change course: Use the tiller or steering wheel to smoothly transition the boat without losing speed or control.

6. Trim the jib: Once the turn is complete, bring the jib sail back into the appropriate position for optimal performance.

7. Prioritize stability and balance: Make necessary adjustments to ensure that the boat remains stable and well-balanced throughout the jibing process.

Remember, practice makes perfect! Regular practice will help you improve your jibing skills and allow you to experience more efficient and enjoyable sailing.

Some Facts About How To Jibe A Sailboat:

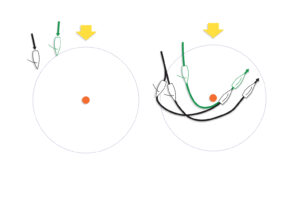

- ✅ To jibe, follow these three steps: start from a broad reach, release the preventer and turn downwind, wait for the jib to jibe itself, then pull the mainsail amidships and ease it out on the new tack.

- ✅ Tips for jibing safely include trimming the jib sheet once it crosses, using a slow turn, keeping control of the mainsail, easing the main quickly, watching the course to prevent rounding up, and not being shy about jibing.

- ✅ If the jib jibes unexpectedly, immediately head up to prevent an uncontrolled jibe and secure the boom with a preventer.

- ✅ There are two methods to jibe a Gennaker: snuffing the spinnaker and re-lead the sheet, or jibing while still flying by tensioning the windward sheet and releasing the working sheet.

- ✅ Jibing a Gennaker while still flying requires trimming the sail before jibing the boat to prevent the spinnaker from blowing through or wrapping around the forestay.

Frequently Asked Questions

How to jibe a sailboat in normal position.

To jibe a sailboat in normal position, follow these three steps:

- Start from a broad reach.

- Release the preventer and turn downwind.

- Wait for the jib to jibe itself, then pull the mainsail amidships and ease it out on the new tack.

What are some tips for jibing a sailboat in the breeziest conditions?

When jibing a sailboat in the breeziest conditions, consider these tips:

- Trim the jib sheet once it crosses.

- Use a slow turn to maintain control.

- Keep control of the mainsail.

- Ease the main quickly.

- Watch the course to prevent rounding up.

- Don’t be shy about jibing.

What should I do if the jib jibes unexpectedly?

If the jib jibes unexpectedly, immediately head up to prevent an uncontrolled jibe and secure the boom with a preventer.

How do I jibe a Gennaker in a sailboat?

There are two methods to jibe a Gennaker:

- Snuff the spinnaker and re-lead the sheet.

- Jibe while still flying by tensioning the windward sheet and releasing the working sheet.

What are the steps to jibe a Gennaker while still flying?

To jibe a Gennaker while still flying, follow these steps:

- Trim the sail before jibing the boat to prevent the spinnaker from blowing through or wrapping around the forestay.

- Jibe the boat while maintaining tension on the windward sheet.

- Release the working sheet gradually.

What are the steps to jibe a spinnaker in a sailboat?

To jibe a spinnaker in a sailboat, you can use the easiest technique:

- Snuff the sail.

- Drop the pole to the deck.

- Pull the snuffed spinnaker around the bow with the sheets.

- Jibe the main.

- Reset the pole.

- Redeploy the spinnaker.

About the author

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest posts

The history of sailing – from ancient times to modern adventures

History of Sailing Sailing is a time-honored tradition that has evolved over millennia, from its humble beginnings as a means of transportation to a beloved modern-day recreational activity. The history of sailing is a fascinating journey that spans cultures and centuries, rich in innovation and adventure. In this article, we’ll explore the remarkable evolution of…

Sailing Solo: Adventures and Challenges of Single-Handed Sailing

Solo Sailing Sailing has always been a pursuit of freedom, adventure, and self-discovery. While sailing with a crew is a fantastic experience, there’s a unique allure to sailing solo – just you, the wind, and the open sea. Single-handed sailing, as it’s often called, is a journey of self-reliance, resilience, and the ultimate test of…

Sustainable Sailing: Eco-Friendly Practices on the boat

Eco Friendly Sailing Sailing is an exhilarating and timeless way to explore the beauty of the open water, but it’s important to remember that our oceans and environment need our protection. Sustainable sailing, which involves eco-friendly practices and mindful decision-making, allows sailors to enjoy their adventures while minimizing their impact on the environment. In this…

Parts Of a Sail Explained (Illustrated Beginners Guide)

Are you curious about sail mechanics and how they engage the wind? In this illustrated guide, we'll explain the various sail components and how they work together to propel a sailboat. From the head to the foot, the tack to the clew, we'll break down each part and give you a solid foundation to build on as you learn to trim sails and navigate the open sea.

A sail, which is a large piece of fabric that is attached to a long pole called the mast, uses the wind to pull a sailboat across the water. It has various parts, such as the head, tack, clew, luff, leech, foot, mainsail, jib, and batten. These components determine the shape and efficiency of the sail.

Let's break down all these terms and descriptions to understand how each component interacts with each other. So, whether you're a seasoned sailor or a beginner, you'll have a better grasp of sail trim and optimal performance on the water.

- The primary parts of a mainsail include the head, tack, clew, luff, leech, and foot.

- Some critical elements of the jib include the sheet, genoa, and headstay.

- Asymmetrical spinnakers are designed for off-wind sailing and have a more rounded shape, while symmetrical spinnakers are used for downwind sailing and have a more traditional, triangular shape.

- The most common fabrics used for making sails are traditional fabrics like cotton and flax, and modern fabrics such as polyester and nylon, Dacron, Mylar, and laminates.

- Be sure to learn how to properly trim, reef, clean, flake, and store your sails for durability and optimal performance.

On this page:

Parts of a sail and their functions, mainsail components, jib components of a sailboat, components of spinnakers, sail controls and settings, sail care and maintenance, sail materials and construction.

In this guide, we'll focus on the three main types of sails : Mainsail, Jib, and Spinnaker.

Mainsail is the primary sail on your boat

The mainsail is the largest sail on a sailboat and is typically attached to the mast and boom. It is found aft (rear) of the mast. It's attached to the boat through a track or sail slide, which allows it to move up and down.

Jib is a triangular sail placed in front of the boat

The jib is a smaller sail that is attached to the bow of the boat and works in conjunction with the mainsail to control the direction and speed of the boat. It helps to improve the boat's handling and increase speed, working in tandem with the mainsail.

In some cases, larger jibs called genoas are used to capture more wind, thus increasing the boat's speed.

Spinnaker is designed for sailing downwind

The spinnaker is a large, colorful, and lightweight balloon-shaped sail designed for sailing downwind. It captures the wind from the rear, pushing the boat forward with added speed and stability.

In this section, you'll find a comprehensive explanation of the primary components of a sail and their functions:

Head is the uppermost corner of a sail

The head of the sail refers to the uppermost corner where it connects to the top of the mast. Knowing the location of the head is essential, as it helps you identify the top of the sail and allows you to properly hoist and secure it in place.

Tack is the lower front corner of a sail

The tack is where the lower front corner connects to the base of the mast, or the boom. This important point helps you determine the sail's orientation and affects its overall shape and efficiency. By adjusting the tension at the tack, you can control your sail's performance and handling in various wind conditions.

Clew is the lower rear corner of a saisl

The clew is where the sheets attach to control the sail's angle to the wind. Adjusting the tension on the sheets can change the sail's shape and ultimately influence the boat's speed and direction. Becoming familiar with the clew will help improve your sailing skills and ensure smooth maneuvers on the water.

Luff is the front edge of the sail

The luff is the forward edge of the sail that runs along the mast. It's crucial to maintaining a tight and efficient sail shape. When sailing upwind, pay close attention to the luff, as it can provide valuable information about your sail's trim. A properly trimmed sail will have a smooth luff, allowing the boat to move efficiently against the wind.

Leech is the rear edge of the sail

The leech is opposite the luff. It plays a critical role in controlling the overall shape and efficiency of your sail. Watch the leech carefully while sailing, as excessive tension or looseness can negatively affect your sail's performance. Adjusting your sail's trim or using a device called a "boom vang" can help control the shape and tension of the leech.

Foot is the bottom edge of the sail

The foot is running between the tack and the clew. It helps control the shape and power of the sail by adjusting the tension along the boom. Ensure the foot is properly trimmed, as this can impact your boat's performance and speed. A well-adjusted foot helps your sail maintain its proper shape and operate at optimal efficiency while out on the water.

In this section, we'll look at some critical elements of the jib: the sheet, genoa, and headstay.

Sheet is the line used to control the position and trim of the sail