INTRODUCTION TO SAILBOAT DESIGN: A TECHNICAL EXPLORATION

Sailboat design is a complex and fascinating field that blends engineering, hydrodynamics, and aesthetics to create vessels that harness the power of the wind for propulsion. In this highly technical article, we will delve into the key aspects of sailboat design, from methodology to evaluation.

1) Design Methodology

Designing a sailboat is a meticulous process that begins with defining the vessel’s purpose and performance goals. It involves understanding the intended use, whether it’s racing, cruising, or a combination of both. Sailboat designers must also consider regulatory requirements and safety standards.

Once the design objectives are established, naval architects employ various computational tools and simulations to create a preliminary design. These tools help in predicting the boat’s performance characteristics and optimizing its geometry.

Design methodology also encompasses market research to understand current trends and customer preferences. This information is critical for creating a sailboat that appeals to potential buyers.

2) Hull Design

The hull is the heart of any sailboat. Its shape determines how the boat interacts with the water. Hull design encompasses the choice of hull form, its dimensions, and the material used. The hull’s shape affects its hydrodynamic performance, stability, and overall handling.

For example, a narrow hull design with a deep V-shape is ideal for speed, while a wider, flatter hull provides stability for cruising. The choice of materials, such as fiberglass or aluminum, impacts the boat’s weight and durability.

The hull design is a balance between achieving efficient hydrodynamics and providing interior space for accommodations. As a designer, finding this equilibrium is a constant challenge.

3) Keel & Rudder Design

The keel and rudder are critical components of a sailboat’s underwater structure. The keel provides stability by preventing the boat from tipping over, while the rudder controls its direction. Keel design involves selecting the keel type (fin, bulb, or wing) and optimizing its shape for maximum hydrodynamic efficiency.

Rudder’s design focuses on ensuring precise control and maneuverability. Both components must be carefully integrated into the hull’s design to maintain balance and performance.

Keel and rudder design can be particularly challenging because they influence the boat’s behavior in different ways. A well-designed keel adds stability but also increases draft, limiting where the boat can sail. Rudder design must account for both responsiveness and the risk of stalling at high speeds.

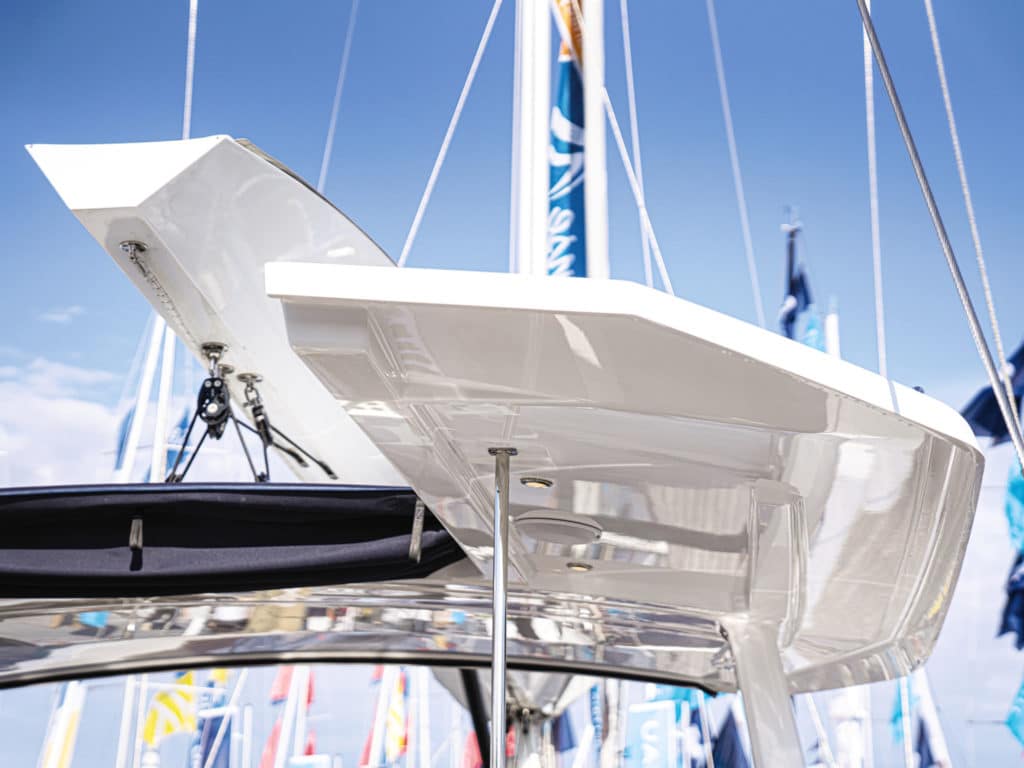

4) Sail & Rig Design

Sail and rig design play a pivotal role in harnessing wind power. Sail choice, size, and shape are tailored to the boat’s intended use and performance goals. Modern sail materials like carbon fiber offer lightweight and durable options.

The rig design involves selecting the type of mast (single or multiple), rigging configuration, and mast height. These choices influence the sailboat’s stability, maneuverability, and ability to handle varying wind conditions.

Balancing the sails and rig for optimal performance is a meticulous task. The sail plan should be designed to efficiently convert wind energy into forward motion while allowing for easy adjustments to adapt to changing conditions.

5) Balance

Balancing a sailboat is crucial for its performance and safety. Achieving the right balance involves a delicate interplay between the hull, keel, rudder, and sail plan. Proper balance ensures the boat remains stable and responds predictably to helm inputs, even in changing wind conditions.

Balance is not a static concept but something that evolves as the boat sails in different wind and sea conditions. Designers must anticipate how changes in load, wind angle, and sail trim will affect the boat’s balance.

Achieving balance is both an art and a science, and it often requires iterative adjustments during the design and testing phases to achieve optimal results.

6) Propulsion

While sailboats primarily rely on wind propulsion, auxiliary propulsion systems like engines are essential for maneuvering in harbors or during calm conditions. Integrating propulsion systems seamlessly into the boat’s design requires careful consideration of engine placement, fuel storage, and exhaust systems.

The choice of propulsion system, whether it’s a traditional diesel engine or a more eco-friendly electric motor, also impacts the boat’s weight distribution and overall performance.

7) Scantling

Scantling refers to the selection of structural components and their dimensions to ensure the boat’s strength and integrity. It involves determining the appropriate thickness of the hull, deck, and other structural elements to withstand the stresses encountered at sea.

Scantling is a critical aspect of sailboat design, as it directly relates to safety. A well-designed boat must be able to withstand the forces exerted on it by waves, wind, and other environmental factors.

8) Stability

Stability is a critical safety factor in sailboat design. Both upright hydrostatics and large-angle stability must be carefully assessed and optimized. This involves evaluating the boat’s center of gravity, ballast, and hull shape.

Achieving the right balance between initial stability, which provides comfort to passengers, and ultimate stability, which ensures safety in adverse conditions, is a delicate task. Designers often use stability curves and computer simulations to fine-tune these characteristics.

9) Layout

The layout of a sailboat’s interior and deck spaces is a blend of functionality and comfort. Designers must consider the ergonomics of living and working aboard the vessel, including cabin layout, galley design, and storage solutions. The deck layout influences crew movements and sail handling.

Layout design also extends to considerations like ventilation, lighting, and noise control. Sailboats are unique in that they must provide both comfortable living spaces and efficient workspaces for handling sails and navigation.

10) Design Evaluation

The final phase of sailboat design involves rigorous evaluation and testing. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, tank testing, and real-world sea trials help validate the design’s performance predictions. Any necessary adjustments are made to fine-tune the vessel’s behavior on the water.

The evaluation phase is where the theoretical aspects of design meet the practical realities of the sea. It’s a crucial step in ensuring that the sailboat not only meets but exceeds its performance and safety expectations.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, sailboat design is a highly technical field that requires a deep understanding of hydrodynamics, engineering principles, and materials science. Naval architects and yacht designers meticulously navigate through the intricacies of hull design, keel and rudder configuration, sail and rig design, balance, propulsion, scantling, stability, layout, and design evaluation to create vessels that excel in both form and function. The harmonious integration of these elements results in sailboats that are not just seaworthy but also a joy to sail, and this process is a testament to the art and science of sailboat design.

Click here to read about “ HARNESSING THE POWER OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN BOAT DESIGN “

Follow my Linkedin Newsletter here: “LinkedIn Newsletter”

0 comments Leave a reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Posts

- KEY LESSONS I LEARNED FROM MY FREELANCE JOURNEY IN 2023

- THE FREELANCE ECONOMY: KEY TRENDS AND PREDICTIONS FOR 2024

- THE RISE Of HDPE IN BOAT MANUFACTURING: TRENDS & BENEFITS

- THE CRITICAL ROLE OF FEASIBILITY STUDY IN BOAT DESIGN AND NAVAL ARCHITECTURE

- THE CHALLENGES Of SMALL CRAFT DESIGN COMPARED TO LARGER VESSELS

Recent Comments

- Casey Lim on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- BRYN BONGBONG on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- Keith on HDPE BOAT PLANS

- Daniel Desauriers on WHY HDPE BOATS?

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- September 2022

- January 2021

- ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

- boatbuilder

- BOAT CONSTRUCTION TECHNIQUES

- BOAT DESIGN COST

- boatdesign process

- CAREER PATHWAYS

- COMMERCIAL BOATS

- conventional boats

- custom boat

- DESIGN ADMINISTRATION

- DESIGN SPIRAL

- EXTREME CONDITIONS

- FEASIBILITY STUDY

- Freelance advantage

- freelance boat designer

- FREELANCE ECONOMY

- FREELANCE JOURNEY

- FRP Boat without Mold

- HDPE Collar

- INDIA'S MARITIME

- INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

- ISO STANDARDS

- Mass Production

- Monhull vs Catamaran

- Naval Architect

- Naval Architecture

- PLANING HULL

- Project Management

- Proven Hull

- PSYCHOLOGY OF BOAT DESIGN

- QUALITY CONTROL

- RECREATIONAL BOATS

- RISE OF HDPE

- ROYALTY AGREEMENTS

- SANDWICH VS SINGLE SKIN

- SOLOPRENEUR

- YACHT DESIGN COURSE

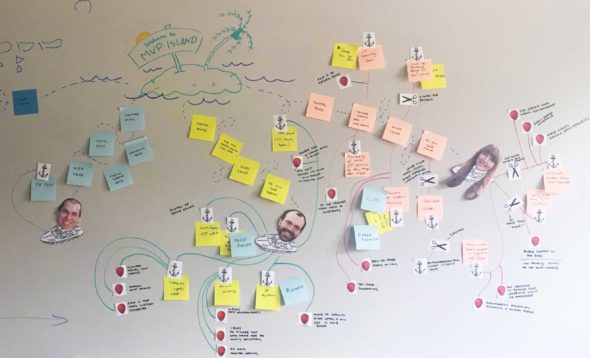

Sailboat Retrospective

You know the term ‘smooth sailing’? Imagine you could apply it to all of your current projects and future sprints. Using the Sailboat Retrospective technique can help you achieve team cohesiveness using a fun, visual exercise that gets all of your team members on the same page — or should we say— boat.

What exactly is a Sailboat Retrospective?

The Sailboat technique for retrospectives is a fun, interactive, and low-key way for your team to reflect on a project. It helps team members to identify what went right, what went wrong, and what improvements and changes can be made in the future. Usually the retrospective happens immediately after the completion of a project or sprint.

This technique uses the metaphor of a sailboat heading toward shore to help teams visualize their ship (team) reaching its ultimate destination (or ultimate goals).

Let’s look at a quick breakdown of the pieces involved:

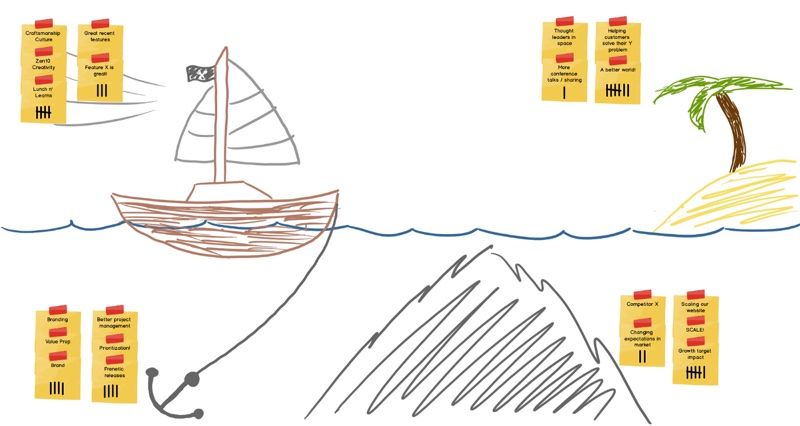

Anatomy of the Sailboat Retrospective

In a Sailboat exercise, there are traditionally five main components:

- The sailboat: The team itself (or some teams prefer to make this the project)

- The island or shore: The ultimate goal or vision for the team (where it’s headed)

- The wind (or the sails): Things that are helping the team glide along (team strengths, competitive advantages of your product, good communication, etc.)

- The anchors: things that are slowing the team or project down or delaying progress (silos, areas of weakness, etc.)

- The rocks: the risks or potential pitfalls of a project (areas of tension, bottlenecks, competition, etc.)

Some Sailboat Retrospectives incorporate other aspects that fit into their vision such as the sun, which represents things that make the team feel happy or satisfied; or, choppy waves to represent something the team feels anxious about.

Some teams even scale their sails for bigger vs. smaller problems. If you have quite a few people involved in your retrospective or you have a lot of issues and need a way to prioritize, this is an option.

Feel free to get creative and add any aspects you feel would be beneficial to your retrospective. (This can be easily done via our Sailboat Retrospective template by adding additional columns. See below.)

Why is the Sailboat Retrospective technique so effective?

The effectiveness of the Sailboat Exercise lies in its ability to use relatable metaphors to help team members easily identify important strengths and weaknesses. Because it is more of a non-pressure approach, it can help team members feel relaxed and more open to communicate without overthinking things.

This exercise is a fun way to get your team out of their day-to-day and think about the ‘big-picture’ to continually improve processes. It can also be a nice way of mixing up your retrospectives to keep them fresh and engaging.

And just because it’s fun doesn’t mean it’s not effective! The average Sailboat Retrospective normally helps to identify around 3-5 action items . That’s 3-5 new ways that your team can enhance their performance!

How to run one with your team

Ready to try your own Sailboat method retrospective?

Note: This exercise should take around 60 to 90 minutes to complete.

1. First, gather your key stakeholders

Usually, a retrospective includes the Scrum Master, Product Owner and members of the Scrum team. If there are other key stakeholders for your specific project invite them to the retrospective as well. This specific type of exercise really benefits from having different opinions and perspectives.

If your team is distributed or remote (as many are these days) you can still perform the Sailboat Exercise. Consider using a great online tool designed specifically to help distributed teams facilitate retrospectives.

2. Set some ground rules

It’s important to set the tone for how you envision your retrospective going. There are a few things that should never be included in any retrospective, and the Sailboat method is no exception. Keep your retrospective free of:

And make sure the focus is on:

- Having a growth mindset

- Being optimistic

- Being open-minded and open to constructive criticisms

- Being a psychologically-safe environment

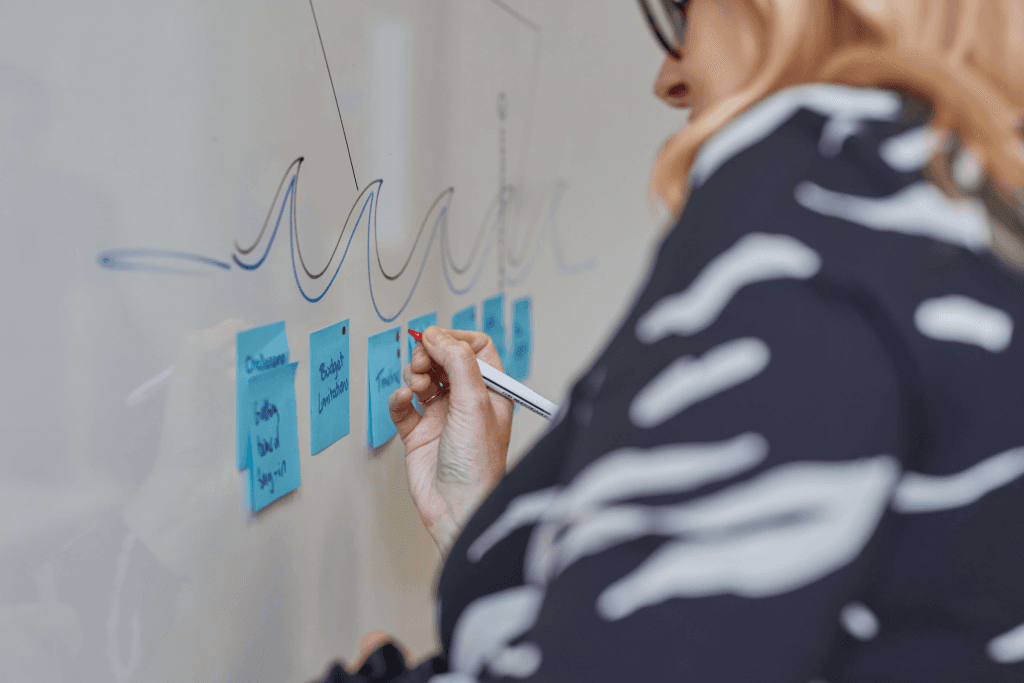

3. Sketch your Visual

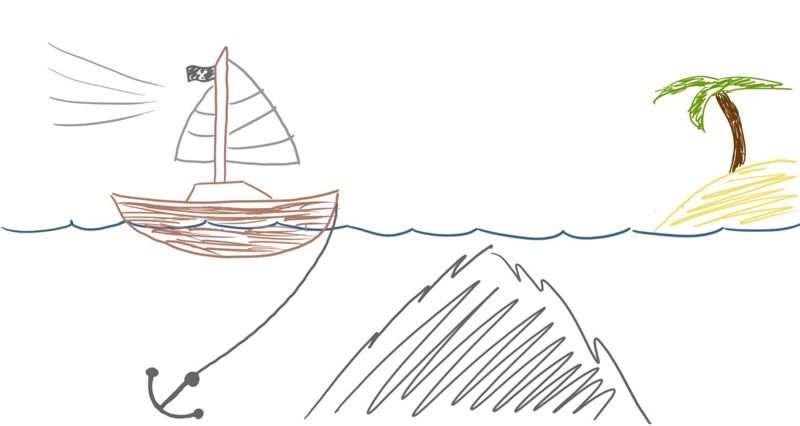

The rough sketch below is a pretty standard depiction for this type of retrospective. If you don’t want to draw your own, a simple Google search of sample Sailboat Retrospective images can help you find more examples.

Your visual should include all of the elements you’ll be discussing in order to help facilitate the exercise.

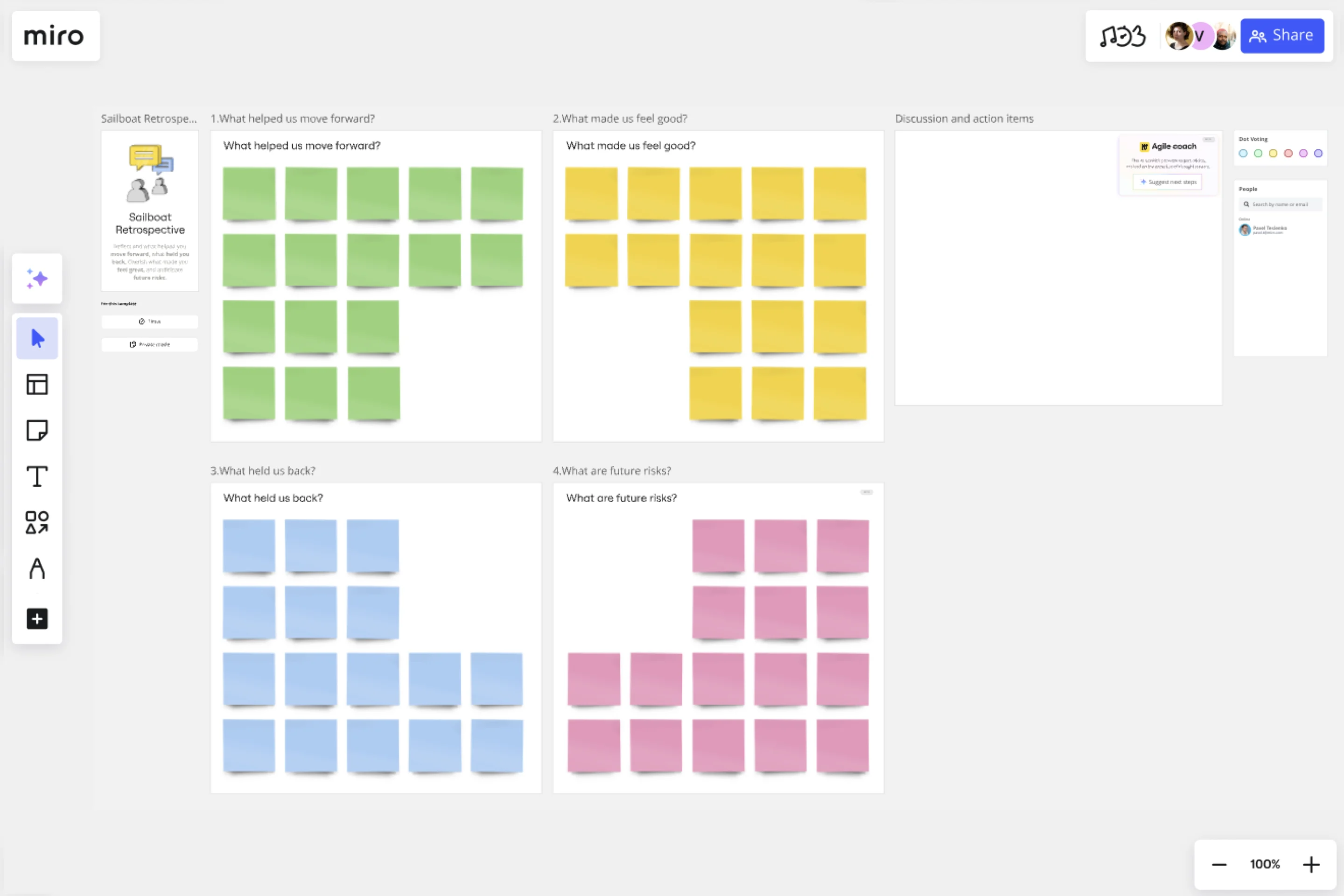

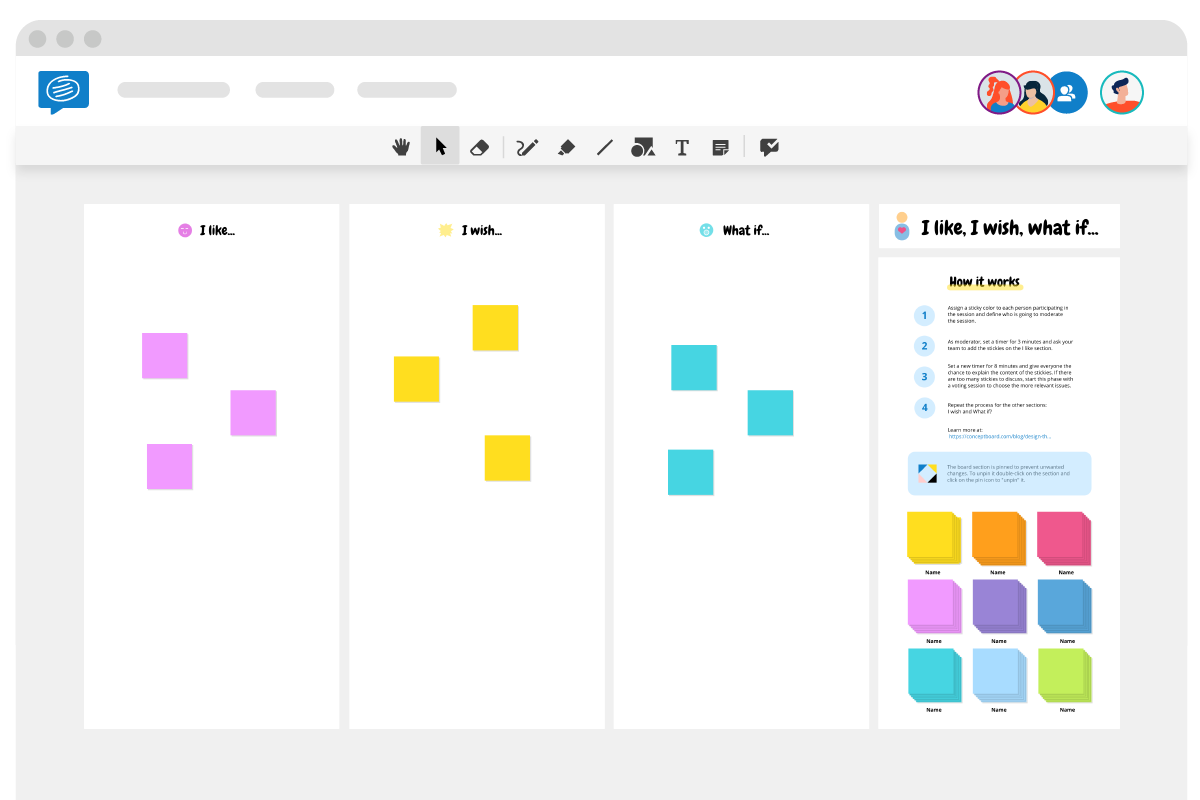

4. Set up your Template

Next, you’ll want to set up the template you’ll be using to capture your team’s thoughts. You can use a white board and post-its for this, but we’d suggest using an easy-to-build online template ( like this one ) to keep things organized.

Add all of the categories you will be discussing to your template. Then, take a few minutes to explain in detail what each category represents.

5. Brainstorming and/or discussion

Once your categories are all laid out on your template, you can either ask your team to quietly brainstorm for each one, or you can hold a group discussion. Really, this depends on the communication style of your team.

If you feel it might be better to have team members submit their feedback anonymously, they can write out their notations on post-its and you can gather them before discussion. Once you have everyone’s thoughts and additions, add them to your template.

This is the final phase of the retrospective. At this point, you and your team should identify what the biggest successes of your project were and what attributes you’d like to carry forward.

Discuss your anchors (obstacles) and brainstorm ways to overcome them. Also discuss ways to mitigate your potential risks (rocks) and how close or far you are from reaching your ultimate goals.

Once everyone is on the same page, conclude your retrospective and move forward with a plan and improved understanding of team performance!

That’s all there is to it! We hope your team enjoys this retrospective and gains some valuable insights along the way.

Happy sailing!

- Types of Sailboats

- Parts of a Sailboat

- Cruising Boats

- Small Sailboats

- Design Basics

- Sailboats under 30'

- Sailboats 30'-35

- Sailboats 35'-40'

- Sailboats 40'-45'

- Sailboats 45'-50'

- Sailboats 50'-55'

- Sailboats over 55'

- Masts & Spars

- Knots, Bends & Hitches

- The 12v Energy Equation

- Electronics & Instrumentation

- Build Your Own Boat

- Buying a Used Boat

- Choosing Accessories

- Living on a Boat

- Cruising Offshore

- Sailing in the Caribbean

- Anchoring Skills

- Sailing Authors & Their Writings

- Mary's Journal

- Nautical Terms

- Cruising Sailboats for Sale

- List your Boat for Sale Here!

- Used Sailing Equipment for Sale

- Sell Your Unwanted Gear

- Sailing eBooks: Download them here!

- Your Sailboats

- Your Sailing Stories

- Your Fishing Stories

- Advertising

- What's New?

- Chartering a Sailboat

Sailboat Design: Stability, Buoyancy and Performance

Simply stated, the first requirement of sailboat design is that the yacht designer's creation is seaworthy; particularly in that it stays afloat and is highly resistant to capsize - but of course we expect rather more than that...

Good sailing performance, particularly to windward, will be high on the list of most sailors' requirements. As will the availability of sufficient space below decks to accommodate the crew and the stores, and all the other sailing paraphernalia.

And the boat must be easy to handle, both under sail at sea and under power in the marina. It must be comfortable, for it's not always just a sailing machine - at times it has to function as a home too.

So a design that successfully incorporates all these requirements won't just happen by accident - but however accomplished your yacht designer, you'll not be able to have everything...

We sailors recognise the stability element of sailboat design as the difference between a 'stiff' boat and a 'tender' one. And whether it's one or the other depends on the relationship between the righting moment applied by the hull and the heeling moment applied by the wind-loaded sails.

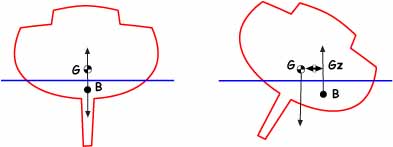

As can be seen in the sketch, the righting moment (Gz) is the horizontal distance between the boat's Centre of Gravity (G) and its Centre of Buoyancy (B).

The righting moment increases as the boat heels until a point is reached at which the heeling moment becomes equal to the righting moment, following which any further increase in heeling moment will cause the boat to capsize.

This is best expressed graphically by way of a Gz Curve, which plots Righting Moment against Heel Angle.

This curve establishes the Angle of Vanishing Stability , effectively the point of no return for a sailboat about to capsize, and which is a major factor in allocating any sailboat to one of the four recognised sailboat design categories - Ocean, Offshore, Inland and Sheltered Waters .

If you're planning to buy or charter a sailboat, you should always check its Design Category to make sure that it's suitable for your purposes.

Displacement, Freeboard and the Centre of Gravity

Heavy displacement boats sit lower in the water than light displacement craft, so their cabin soles are deeper below the water line. Lighter displacement boats with their higher cabin soles have to have greater freeboard to provide their occupants with sufficient headroom.

And freeboard has an impact on stability in that it raises the centre of gravity, thereby reducing the righting moment.

To compensate this, any ballast carried by a light displacement boat should always be as low as possible, ideally in a bulb at the foot of the keel - the lower the centre of gravity the better, as it improves the righting moment by maximising the righting lever Gz.

In our medium-to-light sailboat Alacazam, we have gone one stage further by building in a water ballast system .

Performance

Generally light displacement brings performance benefits due to the higher power to weight ratio and reduced hull drag through having a smaller wetted area.

This is borne out by two important design ratios, the Displacement/Length Ratio and the Sail Area/Displacement Ratio.

Length too has an impact on performance, as can be shown by another sailboat design ratio, the Speed/Length Ratio.

It will also come as no surprise that performance is also influenced by the hull shape below the waterline; a slim arrow-like hull offering less resistance that a squat, dumpy one. But what isn't so widely known is that the ideal shape for hullspeed is not the most efficient shape when sailing at less than hullspeed; which is why sailboat designers ponder long and hard over another sailboat design ratio - the Prismatic Coefficient.

Read more about these and other Design Ratios used by today's Yacht Designers...

Recent Articles

The CSY 44 Mid-Cockpit Sailboat

Sep 15, 24 08:18 AM

Hallberg-Rassy 41 Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 14, 24 03:41 AM

Amel Kirk 36 Sailboat Specs & Key Performance Indicators

Sep 07, 24 03:38 PM

Here's where to:

- Find Used Sailboats for Sale...

- Find Used Sailing Gear for Sale...

- List your Sailboat for Sale...

- List your Used Sailing Gear...

Our eBooks...

A few of our Most Popular Pages...

Copyright © 2024 Dick McClary Sailboat-Cruising.com

- Work With Us

- Project To Product

Run The SailBoat Agile Exercise or Sailboat Retrospective

by Luis Gonçalves on Jun 16, 2024 9:04:15 AM

In this post, I will explain the method known as SailBoat Exercise or Sailboat Retrospective.

This exercise can be found in the book Getting Value out of Agile Retrospectives . A book that I and Ben Linders wrote with a foreword by Esther Derby .

Sailboat Exercise

What you can expect to get out of this technique.

From my experience, this technique is quite appreciated by teams because of its simplicity.

This exercise helps teams to define a vision of where they want to go; it helps them to identify risks during their path and allows them to identify what slows them down and what helps them to achieve their objectives.

When you would use this technique

I believe this method is quite simple and does not require any special occasion. Although, it might be interesting for situations when a retrospective is conducted with more than one team at the same time.

I had a situation, not long time ago that two teams worked together and because of their level of dependency on each other, they decided to conduct a common retrospective because of some ongoing issues.

Using the SailBoat exercise can be extremely interesting because we simply put the name of both teams on the SailBoat and we remind everyone that we are on the same SailBoat navigating in the same direction.

This technique reveals all the good things and less positive things performed by a team.

How to do it

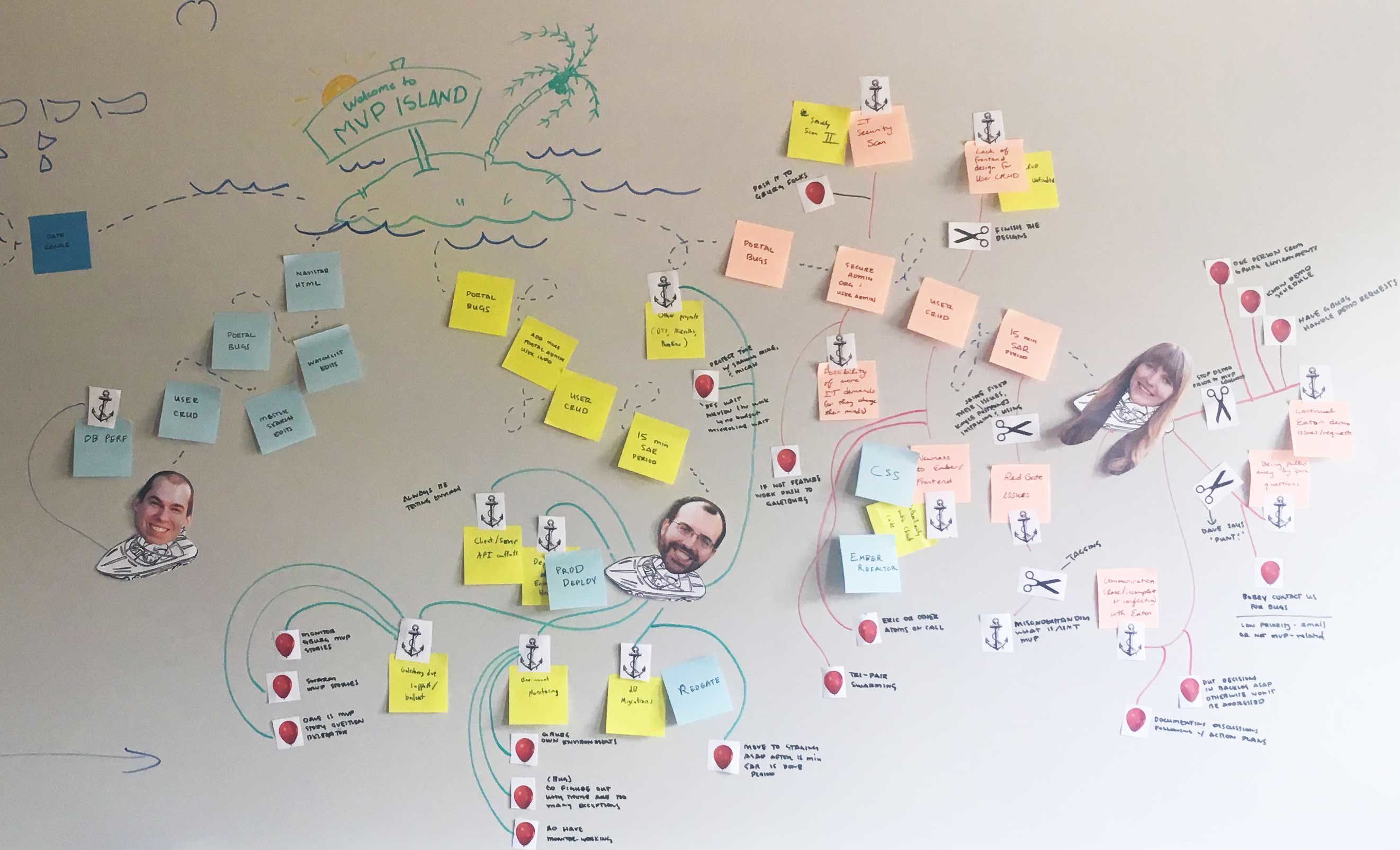

This retrospective is quite simple. First, we draw a SailBoat, rocks, clouds, and a couple of islands like it is shown in the picture on a flip chart.

The islands represent the teams´ goals/vision. They work every day to achieve these islands. The rocks represent the risks they might encounter in their vision.

The anchor on the SailBoat is everything that is slowing them down on their journey. The clouds and the wind represent everything that is helping them to reach their goal.

Having the picture on the wall, write what the team vision is or what our goals are as a team. After that, start a brainstorming session with the team allowing them to dump their ideas within different areas.

Give them ten minutes to write their ideas. Afterward, give 5 minutes to each person to read out loud their ideas.

At this point discuss together with the team how can they continue to practice what was written on the "clouds" area. These are good ideas that help the team, and they need to continue with these ideas.

Then spend some time discussing how can the team mitigate the risks that were identified. Finally, together with the team chose the most important issue that is slowing the team down.

If you do not find an agreement within the team about the most important topic that should be tackled, you can use the vote dots.

In the end, you can define what steps can be done to fix the problem, and you can close the retrospective.

Like many other exercises, this exercise does not require a collocation of a team. You can use, for example, tools like Lino, to apply the exercise to non-collocated teams. This tool allows us to do everything that we need to run this exercise.

What do you think? Your feedback is always extremely important for me, so please leave me your comments.

An Agile Retrospective is an event that ́s held at the end of each iteration in Agile Development and it serves for the team to reflect on how to become more effective, so they can tune and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

I believe the SailBoat exercise is quite a simple Agile Retrospective Exercise and does not require any special occasion.

If you are interested in getting some extra Agile Retrospectives exercises, I created a blog post with dozens of Agile Retrospectives Ideas , check them and see if you find something interesting.

Did you like this article?

We enable leaders to become highly valued and recognized to make an impact on the World by helping them to design Digital Product Companies that will thrive and nourish in the Digital Age, we do this by applying our own ADAPT Methodology® .

- Agile Methodologies (18)

- Product Strategy (18)

- Product Mindset (14)

- Project To Product (10)

- Agile Retrospectives (9)

- Knowledge Sharing (9)

- Time To Market (8)

- Product Discovery (7)

- Continuous Improvement (5)

- Strategy (5)

- Scrum Master (4)

- Content Marketing Strategy (3)

- Product Owner (3)

- Technical Excellency (3)

- Digital Transformation (2)

- Innovation (2)

- Scaling (2)

- Team Building (2)

- Business Model (1)

- Cost Of Delay (1)

- Customer Feedback (1)

- Customer Journey (1)

- Customer Personas (1)

- Design Thinking (1)

- Digital Leadership (1)

- Digital Product Tools (1)

- Go To Market Strategy (1)

- Google Design Sprint (1)

- Lean Budgeting (1)

- Lean Change Management (1)

- Market Solution Fit (1)

- Organisational Impediments (1)

- Outsourcing (1)

- Product (1)

- Product Metrics (1)

- Product Roadmaps (1)

- September 2024 (1)

- August 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (2)

- June 2024 (22)

- May 2024 (8)

- April 2024 (11)

- February 2024 (2)

- January 2024 (152)

- April 2023 (1)

- February 2023 (1)

- July 2021 (1)

- January 2017 (1)

Organisational Mastery

Get your free copy

Product First

- News & Views

- Boats & Gear

- Lunacy Report

- Techniques & Tactics

MODERN SAILBOAT DESIGN: Quantifying Stability

We have previously discussed both form stability and ballast stability as concepts, and these certainly are useful when thinking about sailboat design in the abstract. They are less useful, however, when you are trying to evaluate individual boats that you might be interested in actually buying. Certainly you can look at any given boat, ponder its shape, beam, draft, and ballast, and make an intuitive guess as to how stable it is, but what’s really wanted is a simple reductive factor–similar to the displacement/length ratio , sail-area/displacement ratio , or Brewer comfort ratio –that allows you to effectively compare one boat to another.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to thoroughly analyze the stability of any particular sailboat using commonly published specifications. Indeed, stability is so complex and is influenced by so many factors that even professional yacht designers find it hard to quantify. Until the advent of computers, the calculations involved were so overwhelming that certain aspects of stability were only estimated rather than precisely determined. Even today, with computers doing all the heavy number crunching, stability calculations remain the most tedious part of a naval architect’s job.

There are, however, some tools available that you can use to make a sophisticated appraisal of a boat’s stability characteristics. If you dig and scratch a bit–on the Internet, or by pestering a builder or designer–you should be able to unearth one or more of them.

Stability Curves and Ratios

The most common tool used to assess a boat’s form and ballast stability is a stability curve. This is a graphic representation of a boat’s self-righting ability as it is rotated from right side up to upside down. Stability curves are sometimes published or otherwise made available by designers and builders, but to interpret them correctly, you first need to understand the physics of a heeling sailboat.

When perfectly upright, a boat’s center of gravity (CG)–which is a function of its total weight distribution (i.e., its ballast stability)–and its center of buoyancy (CB)–which is a function of its hull shape (i.e., its form stability)–are vertically aligned on the boat’s centerline. CG presses downward on the boat’s hull while CB presses upward with equal force. The two are in perfect equilibrium, and the boat is motionless. If some force heels the boat, however, CB shifts outboard of CG and the equilibrium is disturbed. The horizontal distance created between CG and CB as the boat heels is called the righting arm (GZ). This is a lever arm, with CG pushing down on one end and CB pushing up on the other, and their combined force, known as the righting moment (RM), works to rotate the hull back to an upright position. The point around which the hull rotates is known as the metacenter (M) and is always directly above CB.

The longer the righting arm (i.e., the larger the value for GZ), the greater the righting moment and the harder the hull tries to swing upright again. Up to a point, as a hull heels more, its righting arm just gets longer. The righting moment, consequently, gets larger and larger. This is initial stability. A wider hull has greater initial stability simply because its greater beam allows CB to move farther away from CG as it heels. Shifting ballast to windward also moves CG farther away from CB, and this too lengthens the righting arm and increases initial stability. The angle of maximum stability (AMS) is the angle at which the righting arm for any given hull is as long as it can be. This is where a hull is trying its hardest to turn upright again and is most resistant to further heeling.

Once a hull is pushed past its AMS, its righting arm gets progressively shorter and its ability to resist further heeling decreases. Now we are moving into the realm of ultimate, or reserve, stability. Eventually, if the hull is pushed over far enough, the righting arm disappears and CG and CB are again vertically aligned. Now, however, the metacenter and CG are in the same place, and the hull is metastable, meanings it is in a state of anti-equilibrium. Its fate hangs in the balance, and the least disturbance will cause it to turn one way or the other. This point of no return is the angle of vanishing stability (AVS). If the hull fails to right itself at this point, it must capsize. Any greater angle of heel will cause CG and CB to separate again, except now the horizontal distance between them will be a capsizing arm, not a righting arm. Gravity and buoyancy will be working together to invert the hull.

Stability at work. The righting arm (GZ) gets longer as the center of gravity (CG) and the center of buoyancy (CB) get farther apart, and the boat works harder to right itself. Past the angle of vanishing stability, however, the righting arm is negative and CG and CB are working to capsize the boat

A stability curve is simply a plot of GZ–including both the positive righting arm and the negative capsizing arm–as it relates to angle of heel from 0 to 180 degrees. Alternatively, RM (that is, both the positive righting moment and the negative capsizing moment) can be the basis of the plot, as it derives directly from GZ. (To find RM in foot-pounds, simply multiply GZ in feet by the boat’s displacement in pounds.) In either case, an S-curve plot is typical, with one hump in positive territory and another hopefully smaller hump (assuming the boat in question is a monohull) in negative territory.

The AMS is the highest point on the positive side of the curve; the AVS is the point at which the curve moves from positive to negative territory. The area under the positive hump represents all the energy that must be expended by wind and waves to capsize the boat; the area under the negative hump is the energy (usually only waves come into play here) required to right the boat again. To put it another way: the larger the positive hump, the more likely a boat is to remain right side up; the smaller the negative hump, the less likely it is to remain upside down.

Righting arm (GZ) stability curve for a typical 35-foot cruising boat. The angle of maximum stability (AMS) in this case is 55 degrees with a maximum GZ of 2.6 feet; the angle of vanishing stability (AVS) is 120 degrees; the minimum GZ is -0.8 feet

The relationship between the sizes of the two humps is known as the stability ratio. If you have a stability curve to work from, there are some simple calculations developed by designer Dave Gerr that allow you to estimate the area under each portion of the curve. To calculate the positive energy area (PEA), simply multiply the AVS by the maximum righting arm and then by 0.63: PEA = AVS x max. GZ x 0.63. To calculate the negative energy area (NEA), first subtract the AVS from 180, then multiply the result by the maximum capsizing arm (i.e., the minimum GZ) and then by 0.66: NEA = (180 – AVS) x min. GZ x 0.66. To find the stability ratio divide the positive area by the negative area.

Working from the curve shown in the graph above for a typical 35-foot cruising boat, we get the following values to plug into our equations: AVS = 120 degrees; max. GZ = 2.6 feet; min. GZ = -0.8 feet. The boat’s PEA therefore is 196.56 degree-feet: 120 x 2.6 x 0.63 = 196.56. Its NE is 31.68 degree-feet: (180 – 120) x -0.8 x 0.66 = 31.68. Its stability ratio is thus 6.2: 196.56 ÷ 31.68 = 6.2. As a general rule, a stability ratio of at least 3 is considered adequate for coastal cruising boats; 4 or greater is considered adequate for a bluewater boat. The boat in our example has a very healthy ratio, though some boats exhibit ratios as high as 10 or greater.

You can run these same equations regardless of whether you are working from a curve keyed to the righting arm or the righting moment. The curve in our example is a GZ curve, but if it were an RM curve, we only have to substitute the values for maximum and minimum RM for maximum and minimum GZ. Otherwise the equations run exactly the same way. The results for positive and negative area, assuming RM is expressed in foot-pounds, will be in degree-foot-pounds rather than degree-feet, but the final ratio will be unaffected.

GZ and RM curves are not, however, interchangeable in all respects. When evaluating just one boat it makes little difference which you use, but when comparing different boats you should always use an RM curve. Because righting moment is a function of both a boat’s displacement and the length of its righting arm, RM is the appropriate standard for comparing boats of different displacements. It is possible for different boats to have the same righting arm at any angle of heel, but they are unlikely to have the same stability characteristics. It always takes more energy to capsize a larger, heavier boat, which is why bigger boats are inherently more stable than smaller ones.

Righting moment (RM) stability curves for a 19,200-pound boat and a 28,900-pound boat with identical GZ values. Because heavier boats are inherently more stable, RM is the standard to use when comparing different boats (Data courtesy of Dave Gerr)

Another thing to bear in mind when comparing boats is that not all stability curves are created equal. There are various methods for constructing the curves, each based on different assumptions. The two most commonly used methodologies are based on standards promulgated by the International Measurement System (IMS), a once popular rating rule used in international yacht racing, and by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Many yacht designers have developed their own methods. When comparing different boats, you must therefore be sure their curves were constructed according to the same method.

Perfect Curves and Vanishing Angles

To get a better idea of how form and ballast relate to each another, it is useful to compare curves for hypothetical ideal vessels that depend exclusively on one type of stability or the other. A vessel with perfect form stability, for example, would be shaped very much like a wide flat board, and its stability curve would be perfectly symmetrical. Its AVS would be 90 degrees, and it would be just as stable upside down as right side up. A vessel with perfect ballast stability, on the other hand, would be much like a ballasted buoy–that is, a round, nearly weightless flotation ball with a long stick on one side to which a heavy weight is attached, like a pick-up buoy for a mooring or a man-overboard pole. The curve for this vessel would have no AVS at all; there would be just one perfectly symmetric hump with an angle of maximum stability of 90 degrees. The vessel will not become metastable until it reaches the ultimate heeling angle of 180 degrees, and no matter which way it turns at this point, it must right itself.

Ideal righting arm (GZ) stability curves: vessel A, a flat board, is as stable upside down as it is right side up; vessel B, a ballasted buoy, must right itself if turned upside down (Data courtesy of Danny Greene)

Beyond the fact that one curve has no AVS at all and the other has a very poor one, the most obvious difference between the two is that the board (vessel A) reaches its point of no return at precisely the point that the buoy (vessel B) achieves maximum stability. A subtler but critical difference is seen in the shape of the two curves between 0 and 30 degrees of heel, which is the range within which sailboats routinely operate. Vessel A achieves its maximum stability precisely at 30 degrees, and the climb of its curve to that point is extremely steep, indicating high initial stability. Vessel B, on the other hand, exhibits poor initial stability, as the trajectory of its curve to 30 degrees is gentle. Indeed, heeling A to just 30 degrees requires as much energy as is needed to knock B down flat to 90 degrees.

Righting arm (GZ) stability curves for a typical catamaran and a typical narrow, deep-draft, heavily ballasted monohull. Note similarities to the ideal curves in the last figure

To translate this into real-world terms, we need only compare the curves for two real-life vessels at opposite extremes of the stability spectrum. The curve for a typical catamaran, for example, looks similar to that of our board since its two humps are symmetrical. If anything, however, it is even more exaggerated. The initial portion of the curve is extremely steep, and maximum stability is achieved at just 10 degrees of heel. The AVS is actually less than 90 degrees, meaning that the cat, due to the weight of its superstructure and rig, will reach its point of no return even before it is knocked down to a horizontal position. The curve for a narrow, deep-draft, heavily ballasted monohull, by comparison, is similar to that of the ballasted buoy. The only significant difference is that the monohull has an AVS, though it is quite high (about 150 degrees), and its range of instability (that is, the angles at which it is trying to capsize rather than right itself) is very small, especially when compared to that of the catamaran.

The catamaran, due to its light displacement and great initial stability, will likely perform well in moderate conditions and will heel very little, but it has essentially no reserve stability to rely on when conditions get extreme. The monohull because of its heavy displacement (much of it ballast) and great reserve stability, will perform less well in moderate conditions but will be nearly impossible to overturn in severe weather.

What Is An Adequate AVS?

In the real world you will rarely come across stability curves for catamarans. If you do find one, you should probably be most interested in the AMS and the steepness of the curve leading up to it. Monohull sailors, on the other hand, should be most interested in the AVS, and as a general rule the bigger this is the better.

Coastal cruisers sailing in protected waters should theoretically be perfectly safe in a boat with an AVS of just 90 degrees. Assuming you never encounter huge waves, the worst that could happen is you will be knocked flat by the wind, and so as long as you can recover from a 90-degree knockdown, you should be fine. It’s nice to have a safety margin, however, so most experts advise that average-size coastal cruising boats should have an AVS of at least 110 degrees. Some believe the minimum should 115 degrees.

For offshore sailing you want a larger margin of safety. Recovering from a knockdown in high winds is one thing, but in a survival storm, with both high winds and large breaking waves, there will be large amounts of extra energy available to help roll your boat past horizontal. There is near-universal consensus that bluewater boats less than 75 feet long should have an AVS of at least 120 degrees. Because larger boats are inherently more stable, the standard for boats longer than 75 feet is 110 degrees.

The reason 120 degrees is considered the minimum AVS standard for most bluewater boats is quite simple. Naval architects figure that any sea state rough enough to roll a boat past 120 degrees and totally invert it will also be rough enough to right it again in no more than 2 minutes. This, it is assumed, is the longest time most people can hold their breaths while waiting for their boats to right themselves. If you don’t ever want to hold your breath that long, you want to sail offshore in a boat with a higher AVS.

Estimated times of inversion for different AVS values (Data courtesy of Dave Gerr)

As this graph illustrates, an AVS of 150 degrees is pretty much the Holy Grail. A boat with this much reserve stability can expect to meet a wave large enough to turn it right side up again almost the instant it’s turned over.

Other Factors To Consider

Stability curves may look dynamic and sophisticated, but in fact they are based on relatively simple formulas that can’t account for everything that might make a particular boat more or less stable in the real world. For one thing, as with regular performance ratios, the displacement values used in calculating stability curves are normally light-ship figures and do not include the weight that is inevitably added when a boat is equipped and loaded for cruising. Even worse, much of this extra weight–in the form of roller-furling units, mast-mounted radomes, and other heavy gear–will be well above the waterline and thus will erode a boat’s inherent stability. The effect can be quite large. For example, installing an in-mast furling system may reduce your boat’s AVS by as much as 20 degrees. In most cases, you should assume that a loaded cruising boat will have an AVS at least 10 degrees lower than that indicated on a stability curve calculated with a light-ship displacement number.

Another important factor to consider is downflooding. Stability curves normally assume that a boat will take on no water when knocked down past 90 degrees, but this is unlikely in the real world. The companionway hatch will probably be at least partway open, and if the knockdown is unexpected, other hatches may be open as well. Water entering a boat that is heeled to an extreme angle will further destabilize the boat by shifting weight to its low side. If the water sloshes about, as is likely, this free-surface effect will make it even harder for the boat to come upright again.

This may seem irrelevant if you are a coastal cruiser, but if you are a bluewater cruiser you should be aware of the location of your companionway. A centerline companionway will rarely start downflooding until a boat is heeled to 110 degrees or more. An offset companionway, however, if it is on the low side of the boat as it heels, may yield downflood angles of 100 degrees or lower. A super AVS of 150 degrees won’t do much good if your boat starts flooding well before that. To my knowledge, no commonly published stability curve accounts for this factor.

Another issue is the cockpit. An open-transom cockpit, or a relatively small one with large effective drains, will drain quickly if flooded in a knockdown. A large cockpit that drains poorly, however, may retain water for several minutes, and this, too, can destabilize a boat that is struggling to right itself.

This boat has features that can both degrade and improve its stability. The severely offset companionway makes downflooding a big risk during a port tack knockdown or capsize, but the high rounded cabintop and small cockpit footwell will help the boat to right itself

Fortunately, not all unaccounted for stability factors are negative. IMS-based stability curves, for example, assume that all boats have flush decks and ignore the potentially positive effect of a cabin house. This is important, as a raised house, particularly one with a rounded top, provides a lot of extra buoyancy as it is submerged and can significantly increase a boat’s stability at severe heel angles. Lifeboats and other self-righting vessels have high round cabintops for precisely this reason.

ISO-based stability curves do account for a raised cabin house, but not all designers believe this is a good thing. A cabin house only increases reserve stability if it is impervious to flooding when submerged. If it has open hatches or has large windows and apertures that may break under pressure, it will only help a boat capsize and sink that much faster. The ISO formulas fail to take this into account and instead may award high stability ratings to motorsailers and deck-saloon boats with large houses and windows that may be vulnerable in extreme conditions.

Simplified Measures of Stability

In addition to developing stability curves, which obviously are fairly complex, designers and rating and regulatory authorities have also worked to quantify a boat’s stability with a single number. The simplest of these, the capsize screening value (CSV), was developed in the aftermath of the 1979 Fastnet Race. Over a third of the more than 300 boats entered in that race, most of them beamy, lightweight IOR designs, were capsized (rolled to 180 degrees) by large breaking waves, and this prompted a great deal of research on yacht stability. The capsize screening value, which relies only on published specifications and was intended to be accessible to laypeople, indicates whether a given boat might be too wide and light to readily right itself after being overturned in extreme conditions.

To figure out a boat’s CSV divide the cube root of its displacement in cubic feet into its maximum beam in feet: CSV = beam ÷ ³√DCF. You’ll recall that a boat’s weight and the volume of water it displaces are directly related, and that displacement in cubic feet is simply displacement in pounds divided by 64 (which is the weight in pounds of a cubic foot of salt water). To run an example of the equation, let’s assume we have a hypothetical 35-foot boat that displaces 12,000 pounds and has 11 feet of beam. To find its CSV, first calculate DCF–12,000 ÷ 64 = 187.5–then find the cube root of that result: ³√187.5 = 5.72; note that if your calculator cannot do cube roots, you can instead take 187.5 to the 1/3 power and get the same result. Divide that result into 11, and you get a CSV of 1.92: 11 ÷ 5.72 = 1.92.

Interpreting the number is also simple. Any result of 2 or less indicates a boat that is sufficiently self-righting to go offshore. The further below 2 you go, the more self-righting the boat is; extremely stable boats have values on the order of 1.7. Results above 2 indicate a boat may be prone to remain inverted when capsized and that a more detailed analysis is needed to determine its suitability for offshore sailing.

As handy as it is, the CSV has limited utility. It accounts for only two factors–displacement and beam–and fails to consider how weight is distributed aboard a boat. For example, if we load our hypothetical 12,000-pound boat with an extra 2,250 pounds for light coastal cruising, its CSV declines to 1.8. Load it with an extra 3,750 pounds for heavy coastal or moderate bluewater use, and the CSV declines still further, to 1.71. This suggests that the boat is becoming more stable, when in fact it may become less stable if much of the extra weight is distributed high in the boat.

Note too that a boat with unusually high ballast–including, most obviously, a boat with ballast in its bilges rather than its keel–will also earn a deceptively low screening value. Two empty boats of identical displacement and beam will have identical screening values even though the boat with deeper ballast will necessarily be more resistant to capsize.

Another single-value stability rating still frequently encountered is the IMS stability index number. This was developed under the IMS rating system to compare stability characteristics of race boats of various sizes. The formula essentially restates a boat’s AVS so as to account for its overall size, awarding higher values to longer boats, which are inherently more stable. IMS index numbers normally range from a little below 100 to over 140. For what are termed Category 0 races, which are transoceanic events, 120 is usually the required minimum. In Category 1 events, which are long-distances races sailed “well offshore,” 115 is the common minimum standard, and for Category 2 events, races of extended duration not far from shore, 110 is normally the minimum standard. Conservative designers and pundits often posit 120 as the acceptable minimum for an offshore cruising boat.

Since many popular cruising boats were never measured or rated under the IMS rule, you shouldn’t be surprised if you cannot find an IMS-based stability curve or stability index number for a cruising boat you are interested in. You may find one if the boat in question is a cruiser-racer, as IMS was once a prevalent rating system. Bear in mind, though, that the IMS index number does not take into account cabin structures (or cockpits, for that matter), and assumes a flush deck from gunwale to gunwale. Neither does it account for downflooding.

Another single-value stability rating that casts itself as an “index” is promulgated by the ISO. This is known as STIX, which is simply a trendy acronym for stability index. Because STIX values must be calculated for any new boat sold inside the European Union (EU), and because STIX is, in fact, the only government-imposed stability standard in use anywhere in the world, it is likely to become the predominant standard in years to come.

A STIX number is the result of many complex calculations accounting for a boat’s length, displacement, beam, ability to shed water after a knockdown, angle of vanishing stability, downflooding, cabin superstructure, and freeboard in breaking seas, among others. STIX values range from the low single digits to about 50. A minimum of 38 is required by the European Union for Category A boats, which are certified for use on extended passages more than 500 miles offshore where waves with a maximum height of 46 feet may be encountered. A value of at least 23 is required for Category B boats, which are certified for coastal use within 500 miles of shore where maximum wave heights of 26 feet may be encountered, and the minimum values for categories C and D (inshore and sheltered waters, respectively) are 14 and 5. These standards do not restrict an owner’s use of his boat, but merely dictate how boats may be marketed to the public.

The STIX standard has many critics, including many yacht designers who do not enjoy having to make the many calculations involved, but the STIX number is the most comprehensive single measure of stability now available. As such, it can hardly be ignored. Many critics assert that the standards are too low and that a number of 40 or greater is more appropriate for Category A boats and 30 or more is best for Category B boats. Others believe that in trying to account for and quantify so many factors in a single value, the STIX number oversimplifies a complex subject. To properly evaluate stability, they suggest, it is necessary to evaluate the various factors independently and make an informed judgment leavened by a good dose of common sense.

As useful as they may or may not be, STIX numbers are generally unavailable for boats that predate the EU’s adoption of the STIX standard in 1998. Even if you can find a number for a boat you are interested in, bear in mind that STIX numbers do not account for large, potentially vulnerable windows and ports in cabin superstructures, nor do they take into account a boat’s negative stability. In other words, boats that are nearly as stable upside down as right side up may still receive high STIX numbers.

The bottom line when evaluating stability is that no single factor or rating should be considered to the exclusion of all others. It is probably best, as the STIX critics suggest, to gather as much information from as many sources as you can, and to bear in mind all we have discussed here when pondering it.

Related Posts

- BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

Extremely good analysis of the issue. Did you do an engineering degree before law school Charlie? One more thought on stability that is outwith the scope of the indices. In the classic broach, as the vessel rounds up th keel bites the water and makes the turn worse, increasing the apparent wind and angle of heel, making the rudder progressively less effective,until it is powerless at 90 degrees heel. In a centreboarder with the board up, the bow skids off, avoiding a real broach, and hence danger of being forced to the spreaders hitting the water. We were caught in a 25 knot gust with our somewhat oversize spi up, the helmsman fell and let go, yet we never heeled past about 50 degrees. You had some fun on the cboard Che Vive in strong wind from aft. To some extent, this phenomenon mitigates the poorer AVS of the centreboarder. Is it enough? I hope to avoid checking it out in practice

@Neil: You’re right. I think centerboard boats are more stable in some situations, less stable in others, and the situations in which they are more stable are not represented in stability curves. It is an imperfect science, to say the least. For example, a point I probably should have emphasized a bit more strongly in the text is that the capsize screening value was never ever intended to be dispositive. It was only intended to identify boats that should be subjected to a more rigorous analysis. Thus the word “screening.” charlie

Charlie just came across this post while preparing for my next workshop this weekend. It’s flat out great, the best real world explanation of stability I’ve read.

John, Im John. I live in Rural N.C. about 75 minutes inland from New Bern. Im 58, single dad and when my 17 year old graduates next year i will be headed to Thailand….from North Carolina. I will NOT see the Cape to starboard…maybe i will write a book…Panama to Starboard

@John: Coming from you, that’s a real compliment. Thanks, mate!

A bit late in the day given the date of the article. Anyway here goes. The boat properties in this article are obtained under static equilibrium conditions. Thus the moment resistance curve is obtained by calculating the relative positions of the weight of the vessel and the buoyancy force as the hull is caused to rotate or heel- the resistance due to the moment produced by the misalignment of the two forces at various angles of heel. Because the movement takes place extremely slow no account is allowed for the effect of inertia. I would like to make my point my considering the example of a bag of sugar : In the first example (a) the sugar is gently poured from the bag onto the pan of a weigh scale until the required weight is reached , say one pound: thus an oz at a time until the scale pointer is at one pound ! In case (b) the sugar is placed in a bag, and the bag is placed in contact with the scale but then suddenly released. At which point the scale pointer will swing well past the 1 pound mark reaching 2 pounds , and the pointer will oscillate about the one pound mark, eventually coming to rest about this value! In case (c) the bag , instead of being placed in contact with pan is released from a height of one foot before being released. This will cause likely cause the pointer to be bent and a broken weigh scale.

It is a apparent that the properties used to measure a boats stability are derived from the conditions similar to case (a), while in reality they should be deduced from case (c) INERTIA IS IMPORTANT.

Leave a Reply Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Please enable the javascript to submit this form

Recent Posts

- MAINTENANCE & SUCH: July 4 Maine Coast Mini-Cruz

- SAILGP 2024 NEW YORK: Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous

- MAPTATTOO NAV TABLET: Heavy-Duty All-Weather Cockpit Plotter

- DEAD GUY: Bill Butler

Recent Comments

- Gweilo on SWAN 48 SALVAGE ATTEMPT: Matt Rutherford Almost Got Ripped Off! (IMHO)

- Alvermann on The Legend of Plumbelly

- Charles Doane on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- Nick on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- jim on BAYESIAN TRAGEDY: An Evil Revenge Plot or Divine Justice???

- August 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- October 2009

- Boats & Gear

- News & Views

- Techniques & Tactics

- The Lunacy Report

- Uncategorized

- Unsorted comments

Sailboat Template

Reflect as a team on project goals, blockers, and future ambitions.

About the Sailboat Retrospective Template

The Sailboat Retrospective (also known as the Sailboat Agile Exercise) is a low-pressure way for teams to reflect on how they handled a project. Originally based on the Speedboat retrospective by Luke Hohmann, the exercise centers around a sailboat as a metaphor for the overall project, with various elements broken down:

Rocks - represent risks and potential blockers

Anchors - represent issues slowing down the team

Wind - what helped the team move forward, represents the team’s strengths

Sun - what went well, what made the team feel good

By reflecting on and defining these areas, you’ll be able to work out what you’re doing well and what you need to improve on for the next sprint.

When to use a Sailboat Retrospective Template?

If you are part of an Agile team, you know retrospectives are fundamental to improving your sprint efficiency and getting the best out of your team. The Sailboat Retrospective Template helps you organize this Agile ritual with a sailboat metaphor. Everyone describes where they want to go together by figuring out what slows them down and helps them reach their future goals.

Use this template at the end of your sprint to assess what went well and could have been done better.

Benefits of the Sailboat Retrospective Template

When facilitating your team’s retrospective, this template is an easy way for everyone to jot down ideas in a structured manner. The metaphor of a sailboat gliding over water can help team members think about their work as it relates to the overall course of the project, and the ready-made template makes it easy to fill in and add stickies with ideas and feedback.

To run a successful sailboat retrospective meeting, use Meeting mode to lead your team through each frame, set a timer for each section of the template, and control what participants can do on the board.

Create your own sailboat retrospective

Running your own sailboat retrospective is easy, and Miro’s collaborative workspace is the perfect canvas on which to perform the exercise. Get started by selecting the Sailboat Retrospective Template, then take the following steps to make one of your own.

Introduce the sailboat metaphor to your team . For some teammates, this may be the first time they’ve heard the analogy. Explain the four components, and feel free to frame them as questions (for example, “what helps us work to move forward?”, “what held us back?”, “what risks do you see in our future?”, “what made us feel good?”). Then, tie the visual metaphor back to how to run an Agile sprint. Like a sailboat, a sprint also has factors that slow it down, and risks in the face of a goal, target, or purpose to reach.

Ask each team member to write and reflect individually. Give everyone 10 minutes to create their own sticky notes. Ask them to record their thoughts and reflections relevant to each area of the retrospective. Use Miro’s Countdown Timer to keep things on track.

Present your reflections in pairs or small groups. Spend five minutes each taking turns to dig deeper into the insights recorded on each sticky note.

Choose one team member to group similarly-worded insights together. That team member can spot patterns and relationships between the group’s insights. Accordingly, the team can get a sense of which area had the biggest potential impact on the project.

Vote as a team on what the critical issues are to focus on mitigating and developing. Use the Voting Plugin for Miro to decide what’s worth focusing time and effort on. Each person gets up to 10 votes and can allocate multiple votes to a single issue.

Diagnose issues and develop outcomes. Discuss as a team what your follow-up action plans are for maintaining or building on helpful behavior and resolving issues in preparation for future sprints. Add another frame to your board by clicking Add frame on the left menu bar and annotate your team’s insights and next steps.

Dive even deeper into how to make your own sailboat retrospective – and see examples – in our expert guide to making your own sailboat retrospective .

How do you conduct a sailboat retro?

When conducting a sailboat retro, make a space for you and your team to uncover valuable insights, some of which might not be shareable across your organization. For that reason, make sure to adjust your privacy board settings so that only you and your team can access it, and let them know this is a safe space to share ideas and feedback honestly. The Sailboat Retrospective Template is built for you to run your meeting session smoothly, having complete control of how participants can add to the board. Start explaining the concept of the sailboat retro methodology. If they don’t know it already, guide them through your meeting agenda and set the timer for each section. After the meeting, gather insights in another frame on the same board, and thank everyone for contributing to your retro.

What is the sailboat exercise?

The sailboat exercise is a widely known Agile ritual where you and your team can thoroughly analyze what went well during your last sprint and what could have gone better, so you improve in the next one. This meeting format is similar to a brainstorming session. In each quadrant of the sailboat template, ask your team to add their thoughts and feedback. Use the sailboat exercise when you want to improve processes and gather constructive feedback from your team.

Get started with this template right now.

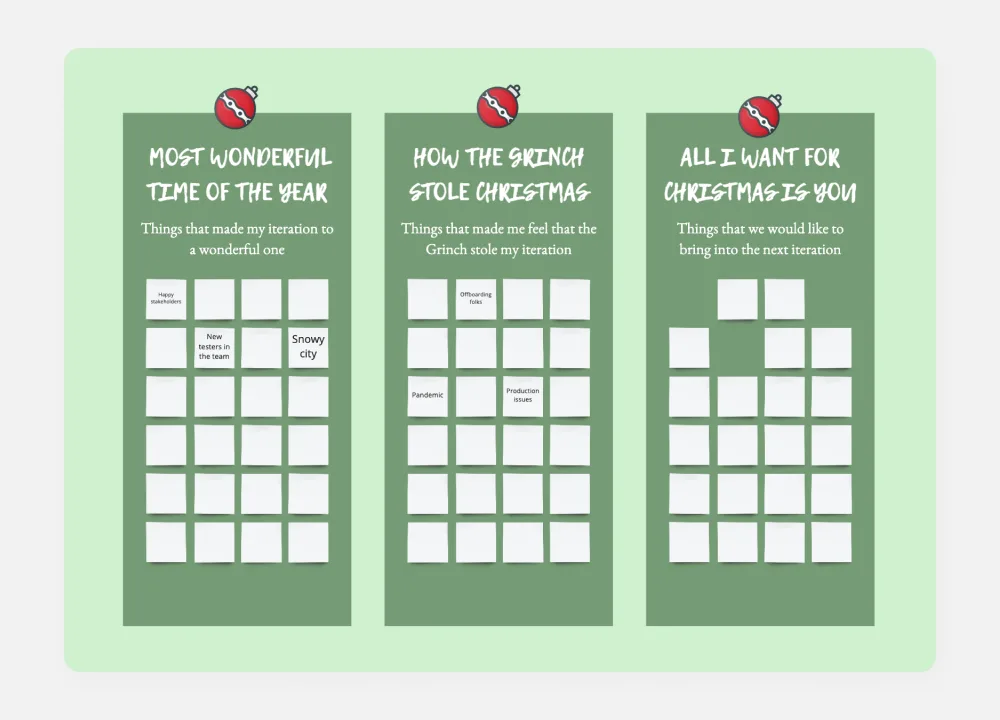

Retrospective - Christmas Edition

Works best for:.

Agile Methodology, Retrospectives, Meetings

The Retrospective Christmas Edition template offers a festive and themed approach to retrospectives, perfect for the holiday season. It provides elements for reflecting on the year's achievements, sharing gratitude, and setting intentions for the upcoming year. This template enables teams to celebrate successes, foster camaraderie, and align on goals amidst the holiday spirit. By promoting a joyful and reflective atmosphere, the Retrospective - Christmas Edition empowers teams to strengthen relationships, recharge spirits, and start the new year with renewed energy and focus effectively.

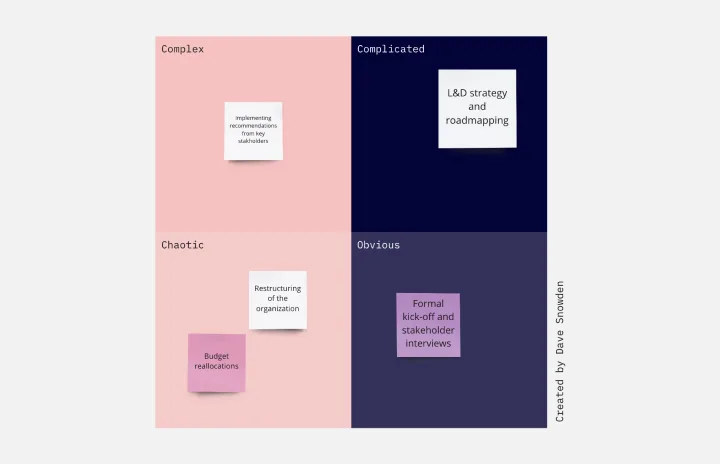

Cynefin Framework Template

Leadership, Decision Making, Prioritization

Companies face a range of complex problems. At times, these problems leave the decision makers unsure where to even begin or what questions to ask. The Cynefin Framework, developed by Dave Snowden at IBM in 1999, can help you navigate those problems and find the appropriate response. Many organizations use this powerful, flexible framework to aid them during product development, marketing plans, and organizational strategy, or when faced with a crisis. This template is also ideal for training new hires on how to react to such an event.

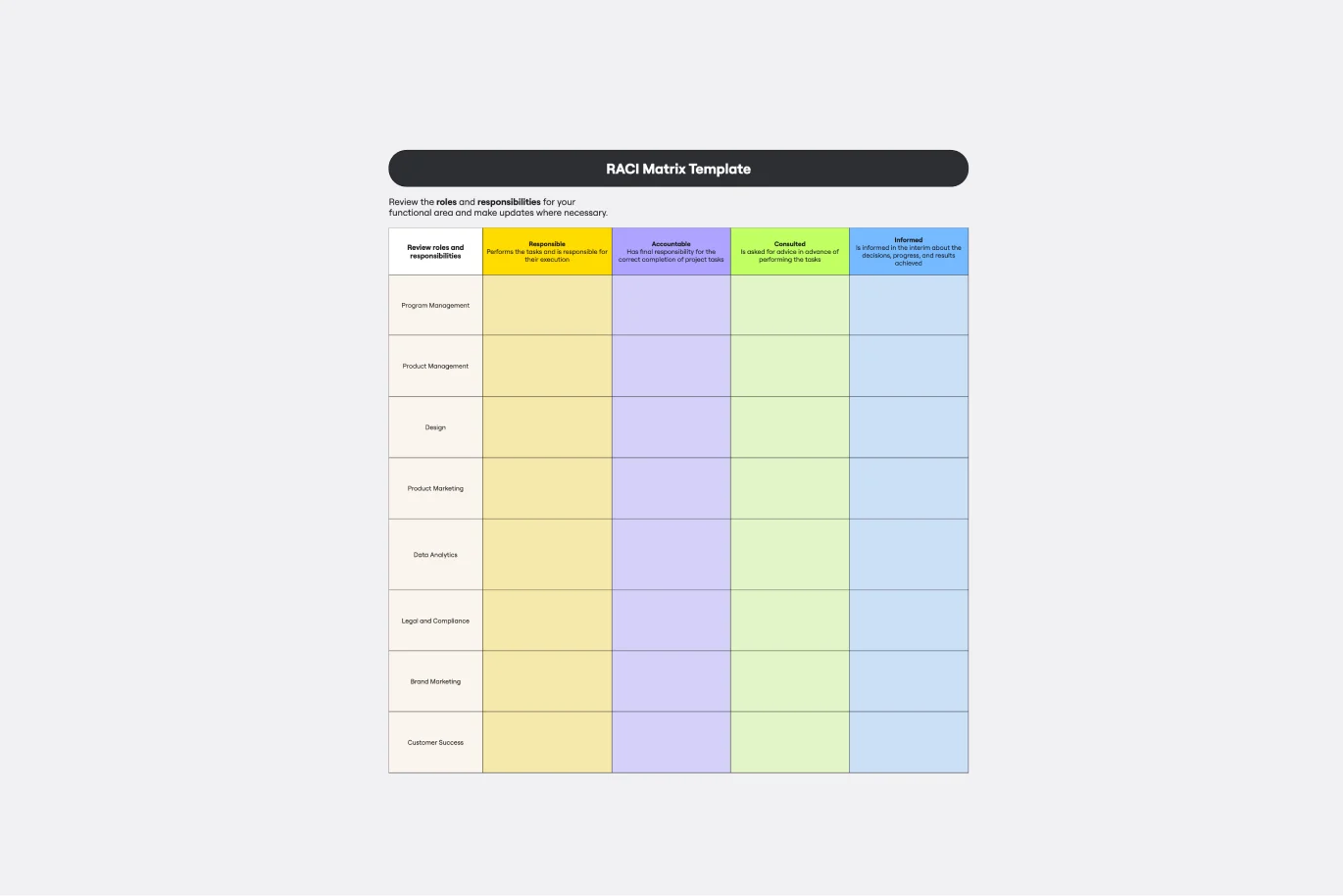

RACI Matrix Template

Leadership, Decision Making, Org Charts

The RACI Matrix is an essential management tool that helps teams keep track of roles and responsibilities and can avoid confusion during projects. The acronym RACI stands for Responsible (the person who does the work to achieve the task and is responsible for getting the work done or decision made); Accountable (the person who is accountable for the correct and thorough completion of the task); Consulted (the people who provide information for the project and with whom there is two-way communication); Informed (the people who are kept informed of progress and with whom there is one-way communication).

Team´s High Performance Tree

Agile, Meetings, Workshops

The Team's High Performance Tree is a visual representation of the factors influencing team performance. It provides a structured framework for identifying strengths, weaknesses, and areas for improvement. By visualizing factors such as communication, collaboration, and leadership, this template enables teams to assess their performance and develop strategies for enhancement, empowering them to achieve peak performance and deliver exceptional results.

Epic & Feature Roadmap Planning

Epic & Feature Roadmap Planning template facilitates the breakdown of large-scale initiatives into manageable features and tasks. It helps teams prioritize development efforts based on business impact and strategic objectives. By visualizing the relationship between epics and features, teams can effectively plan releases and ensure alignment with overall project goals and timelines.

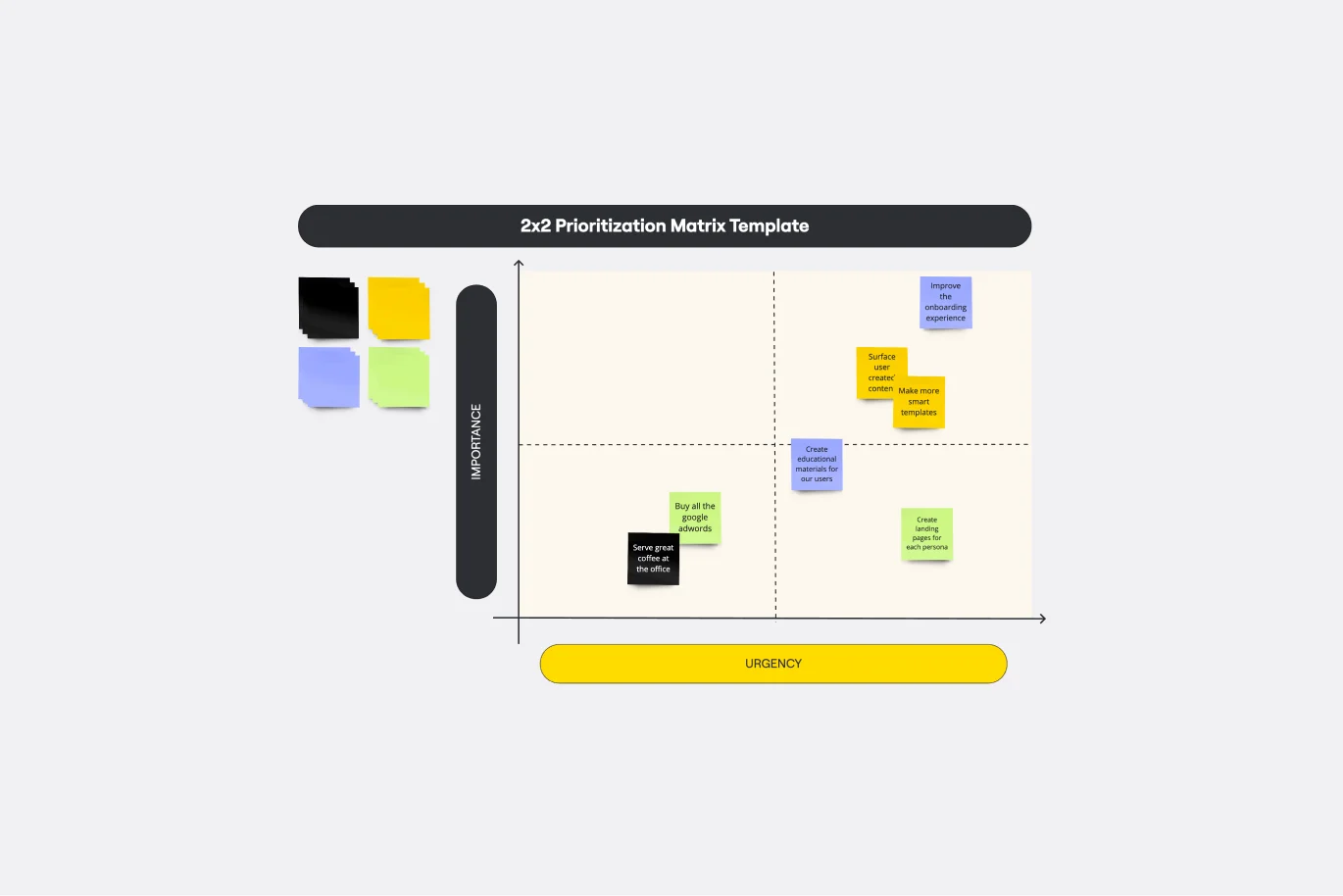

2x2 Prioritization Matrix Template

Operations, Strategic Planning, Prioritization

Ready to set boundaries, prioritize your to-dos, and determine just what features, fixes, and upgrades to tackle next? The 2x2 prioritization matrix is a great place to start. Based on the lean prioritization approach, this template empowers teams with a quick, efficient way to know what's realistic to accomplish and what’s crucial to separate for success (versus what’s simply nice to have). And guess what—making your own 2x2 prioritization matrix is easy.

Retrospectives 102: The Sailboat Method

Summary: After each sprint, the team should have a retrospective session to identify what went well or not so well. The sailboat metaphor is a nice way to structure such retrospectives.

3 minute video by 2020-04-10 3

- Rachel Krause

- Agile Agile ,

- Managing UX Teams ,

Share this article:

- Share this video:

You must have javascript and cookies enabled in order to display videos.

Related Article

UX Retrospectives 101

Retrospectives allow design teams to reflect on their work process and discuss what went well and what needs to be improved. These learnings can be translated into an action plan for future work.

Video Author

Rachel Krause is a Senior User Experience Specialist with Nielsen Norman Group. Her areas of expertise include storytelling, UX in agile, design thinking, scaling design, and UX leadership. She has also planned and conducted research on careers, UX maturity, and intranets for clients and practitioners in numerous industries.

- Share:

Subscribe to the weekly newsletter to get notified about future articles.

MVP: Why It Isn't Always Release 1

4 minute video

Sprint Reviews: Prioritize Your Users

UX in Design Sprints

3 minute video

- Tracking Research Questions, Assumptions, and Facts in Agile

- Incorporating UX Work into Your Agile Backlog

- UX Debt: How to Identify, Prioritize, and Resolve

- Collaborative Agile Activities Reduce Silos and Align Perspectives

- UX Responsibilities in Scrum Events

Research Reports

- UX Metrics and ROI

- Effective Agile UX Product Development

- Architecting a Journey Management Practice: How Leading Organizations Transformed Design Operations to Maximize Business Value

- Operationalizing CX: Organizational Strategies for Delivering Superior Omnichannel Experiences

- Intranet Design Annual: 2018

UX Conference Training Course

- Becoming a UX Strategist

- UX Leader: Essential Skills for Any UX Practitioner

- ResearchOps: Scaling User Research

- Service Blueprinting

- Mastering Influence

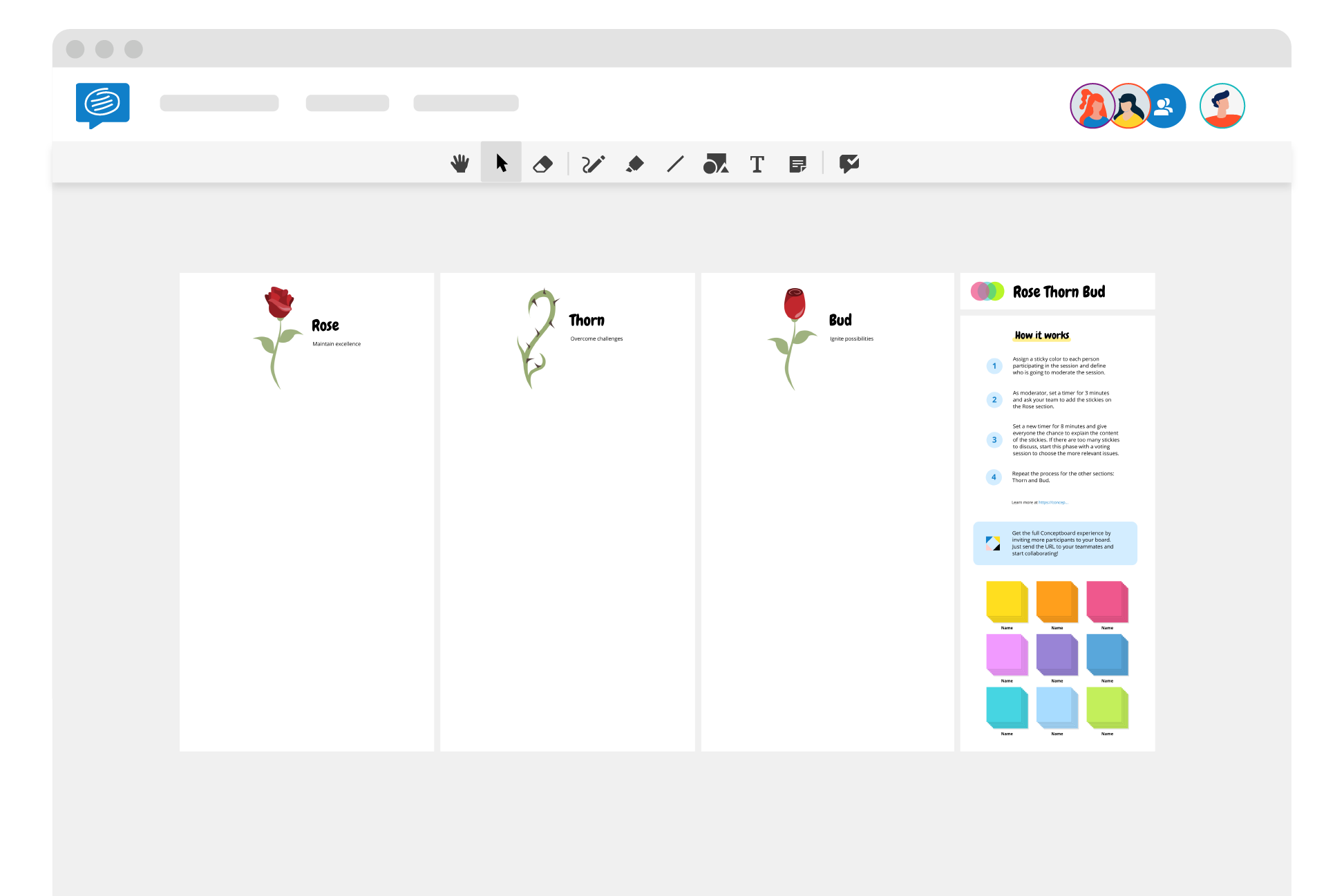

Design Thinking Toolkit, Activity 11 – Speed Boat

Article summary

Basic edition, advanced edition, final thoughts.

- Atomic's Design Thinking Toolkit

Welcome to our series on Design Thinking methods and activities . You’ll find a full list of posts in this series at the end of the page.

Our next activity has us seabound: Speed Boat .

| To understand obstacles preventing achievement of a goal | |

| When you want to assess risks, obstacles, or blockers | |

| On average, 30-60 minutes (add more if you’re running the advanced edition of this activity) | |

| 1 facilitator and 2-10+ participants | |

| Any portion or combination of the team that needs insight into risks and blockers | |

| Large whiteboard or Post-it Tabletop Pad, Post-it notes, Sharpies, whiteboard markers, activity graphics (printed and cut out) |

Speed Boat is the activity you turn to when you want to interject a little life into your process while also framing the obstacles that are holding back the success of your project. Setting it up can be as quick or time-consuming as you’d like to make it. I tend to go the extra mile when it comes to prep-work because the added graphics really help people to engage in the work.

So what is Speed Boat? Simply put, it’s a metaphor that helps you visualize the obstacles that prevent you from achieving your goal. Your project or service is the boat, and anchors are the obstacles, risks, and/or uncompleted tasks preventing you from reaching your destination, the goal.

It’s so easy to get caught up in day-to-day activities that it can become hard to understand why goals aren’t being achieved or where areas of risk have bubbled up. Bust out this activity when you want a quick lay of the land, or in this case, the sea.

You can choose the basic or advanced version of this activity. I’ll begin with the simplest one.

To begin, you’ll need a large whiteboard or wall space, activity graphics of a boat and several anchors, Post-it notes, Sharpies, whiteboard markers, and tape. If you don’t have access to a printer, you can draw the boat and anchors on the board or Post-its as you go, but I’ve found that printed cut-outs make it easier to see the images and move them freely about the board.

Tape your boat to the whiteboard and give it a name, mostly likely your project name. Next, draw an island and put the question you’d like answered at the center of it. This is where you can be really creative with how you structure the activity.

Product and service-related question examples

- What is preventing us from launching?

- Why are users slow to adopt our new technology?

- Why aren’t we standing out from the competition?

- What is preventing users from completing the checkout and payment process?

Personal or non-software related questions

These could be helpful if you’d like to use the framework for something other than project work.

- What is preventing us from achieving our financial goal (like saving for a home, car, or vacation)?

- What is holding me back from running a marathon?

- What is blocking me from having a deeper relationship with my significant other?

- What is keeping my family from gathering together at the dinner table every evening?

Finally, pass out Post-its and Sharpies to each participant, and scatter the anchors about the table so that everyone can grab them as needed.

2. Anchors away!

Present your island question, and explain that the anchors represent obstacles that are slowing down forward progress toward this goal.

Allow participants to ask clarifying questions, and then give them 10 minutes to begin listing anchors. Each Post-it should mention only one anchor.

Once the time is up, ask participants to describe their anchors one by one. Connect the anchors to the boat by sticking the Post-it notes to the board and drawing an anchor line between each note and the boat.

Group any like observations, tasks, and insights together. Finally, ask the group to estimate how much faster the boat would go if all the anchors were cut free.

Take your findings and list them in a spreadsheet, mind map, or backlog so you can keep track of them. You might need to assign owners and dates to some items or tasks to keep moving forward.

Now that you understand the core activity, we’re going to add in two extra elements: scissors and buoys. Scissors are the tasks or ideas that cut an anchor free altogether, and buoys relieve pressure from anchors, but don’t eliminate them completely.

These two extra steps or graphics can help you define solutions for your problems (a.k.a. anchors). They’re helpful if you have extra time and/or a very action-oriented team who wants to assess and take action.

However, they do add an extra 30 minutes or so to the activity, so take your time constraints and group size into consideration when scheduling. Running this activity can be done with a large team, but the process will be more time-consuming.

You’ll prep the activity the same way as the basic edition. However, for this version, there are a few additional graphics (the scissors and buoys) to print and cut ahead of time.

2. Advanced anchors away!

Once again, run the activity as you would in basic mode, all the way to the point where everyone has discussed and posted all of their anchors.

Now that the group has a good sense of everything that’s holding back the boat, ask everyone to gather around the whiteboard to collaboratively post buoys and snip anchor lines with the scissors.

Keep in mind, buoys are ideas, tasks, services, people, etc. that can help relieve pressure from an anchor but cannot cut the anchor line altogether. For example, if an anchor is “poor WIFI connectivity,” a buoy might be “adding another access point,” while a scissor would be “hard-wiring internet capabilities to the device.”

It’s easiest to review one anchor at a time so that the group can brainstorm ideas and discuss the challenges together. It’s also helpful to gain group consensus on how to solve a problem.

Finally, wrap up the activity in the same way as you would for the basic edition.

There are many ways to run Speed Boat, so be creative with your implementation. Most importantly, have fun! Visualizing project risks and obstacles in this way may seem cheesy, but it’s a much more pleasant exercise than wading through the soulless cells of a spreadsheet.

Leave a comment below if you’ve tried this activity, and keep your eyes out for our next activity, Visualizing the Vote!

Atomic’s Design Thinking Toolkit

- What Is Design Thinking?

- Your Design Thinking Supply List

- Activity 1 – The Love/Breakup Letter

- Activity 2 – Story Mapping

- Activity 3 – P.O.E.M.S.

- Activity 4 – Start Your Day

- Activity 5 – Remember the Future

- Activity 6 – Card Sorting

- Activity 7 – Competitors/Complementors Map

- Activity 8 – Difficulty & Importance Matrix

- Activity 9 – Rose, Bud, Thorn

- Activity 10 – Affinity Mapping

- Activity 11 – Speed Boat

- Activity 12 – Visualize The Vote

- Activity 13 – Hopes & Fears