- SYDNEY, NSW

- MELBOURNE, VIC

- HOBART, TAS

- BRISBANE, QLD

- ADELAIDE, SA

- CANBERRA, ACT

- Watch the US Open for free on 9Now

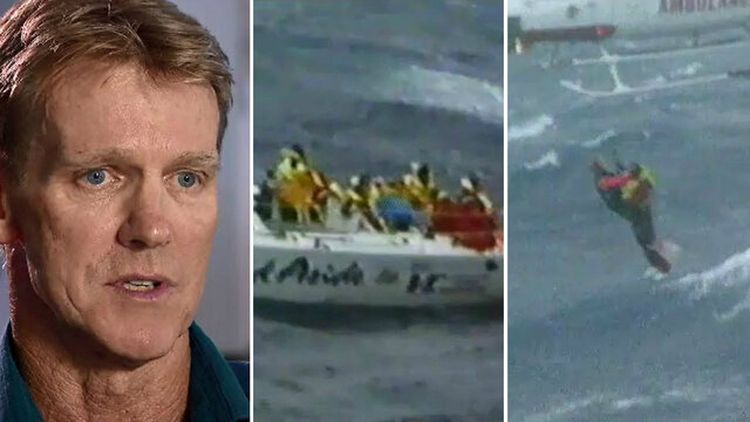

Sydney to Hobart tragedy: Heroes, survivors reflect

- A Current Affair

- SYDNEY TO HOBART

Send your stories to [email protected]

Auto news: Melbourne Tesla owner uses fishing rod to charge car.

Top Stories

Soaring temperatures prompt high fire danger warning for Sydney

The controversial founder of Australian capital city

Aussie gold, teary interview: What you missed on day one

Scaly surprise blends into rocky ground in Victoria

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

1998 Tragedy Haunts Sydney-Hobart Race

By Christopher Clarey

- Dec. 24, 2008

Silence is hard to come by in the annual Sydney-to-Hobart race. There is the drone or the shriek of the wind, the crash of the waves against the hulls, the ominous harmonics of equipment under great stress, and the shouts and mutters from the crews as they try, once again, to sail their yachts of various shapes and prices from the majesty of Sydney Harbor to the haven of Hobart across the Tasman Sea.

But when this year’s race begins on Friday, silence will be a requirement. It has been 10 years since six men died in the storm-swept 1998 edition of this Australian institution, and a minute of silence before the start and another after the finish will honor those sailors as well as others who perished in the race in earlier years.

“I think it is an appropriate way to show our respects to those who didn’t make it; I’m not sure if there’s any other better way to do it,” said Ed Psaltis, who was skipper of the small yacht that won overall honors in 1998 despite the horrific conditions that some ashen competitors compared to a hurricane.

A single wreath will also be laid in Hobart by Matt Allen, commodore of the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, which organizes the race, and Clive Simpson, his counterpart at the Royal Yacht Club of Tasmania. Allen and other club officials have contacted the families of the sailors who died in 1998 and received tentative commitments from some family members to be in attendance in Hobart.

“What happened is part of the history of the race you can’t deny it,” Psaltis said. “One of the guys who died in 1998, Jim Lawler, was a very close friend of my father’s, so it was a personal thing for me.”

He added: “And he was no average yachtie. He was a very accomplished seaman, so to have him perish really knocked me for six. It just showed that even if you are among the best, you can still get taken out. What it shows you, above all, is that the sea is the boss, and you are its servant and don’t even try to think otherwise.”

Larry Ellison, the American billionaire who took line honors in that 1998 race in his maxi Sayonara, gleaned enough amid the 80-knot winds and 60-foot waves to conclude that he never wanted to race the 628 nautical miles from Sydney to Hobart again.

He has been true to his word. He has since focused his big sailing ambitions and budgets on the America’s Cup and other inshore regattas.

But Australians like Psaltis have a more elemental connection to their island nation’s premier yacht race, which was first contested in 1945, just months after the end of World War II. Psaltis, 47, like many a Sydney-to-Hobart skipper, has a regular job that has nothing to do with sailing: He is a partner in Sydney with the accounting firm of Ernst & Young.

Yet despite the torments of 1998 and of other stormy, hazardous years, he has continued to put himself on the starting line. This will be his 28th Sydney-Hobart race, and the 10-member crew on his modified Farr 40, still named Midnight Rambler, will include three other men who sailed with him in 1998: Chris Rockell, John Whitfeld and Bob Thomas, Psaltis’s co-owner and longtime navigator.

“Look, after 1998 I certainly thought very hard about it postrace, along the lines of: I’ve got a wife and three kids. What am I trying to do, to try and kill myself in a stupid yacht race?” Psaltis said. “But I firmly believe that the human spirit wants challenges and actually craves challenges, and to go through life controlled in a regimented, risk-free environment is, I think, no life at all.”

The Hobart as its participants often call it is, however, a more regimented race than it was 10 years ago. Safety requirements have been significantly increased and, as with all offshore races, safety equipment has improved. More of it has been made compulsory, including Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons.

At least 50 percent of each crew must take a course on safety at sea, and 50 percent must have completed a Category 1 ocean race. Sailors under 18 are no longer permitted to take part. The Australian authorities have revised and upgraded their contingency plans for rescue and emergency situations.

“The truth is, 1998 was the biggest maritime rescue operation in the history of Australia,” Allen said. “So I think it’s made people focus.”

He added: “You don’t have, as I’ve seen in some other races around the world, people getting together for one race of the year. Pretty much most of the crews in the Sydney Hobart are people racing pretty much continuously.”

The emphasis on safety has increased costs.

“It probably costs about 60,000 Australian dollars to get the average boat trumped up to do the race,” Psaltis said, or about $41,000. “In 1998, it was 30,000 to 40,000. The cost of sails has gone up. Everything has gone up. But safety is one more issue making it harder.”

The surprise is that the new regulations and the global economic downturn have not affected participation rates. Although there have been some high-profile withdrawals, including a Russian maxi called Trading Network, the fleet of 104 yachts for the race this year is the second-highest number of entrants since 1998.

“I think it’s because people have built boats a while ago or ordered boats a while ago, and that’s probably a reflection of earlier economic times,” Allen said. “People have boats, and they might as well go sailing in them.”

Among those who plan to sail is John Walker, who was already the oldest skipper in the race’s history and is now 86. Rob Fisher and Sally Smith, the children of an avid Sydney-Hobart competitor, will become the first brother and sister to skipper yachts in the race in the same year.

Wild Oats XI, the 98-foot maxi owned by the Australian Bob Oatley, has taken line honors the last three years and is a heavy favorite to become the first yacht to do it four consecutive times. Its crew had to scramble to make final-hour repairs last year, but there have been no such dramas in the run-up to this year’s race.

“These boats are clearly faster than any other boats,” Allen said of the maxis. “It’s more a boat-management issue and seamanship issue for them, and absolutely, to get it there four times in a row unscathed would be a great tribute to the skills of the crew.”

But then, Wild Oats XI has never had to sail through what Ellison and Psaltis endured in 1998.

“We got through it, but only through the skin of our teeth,” Psaltis said. “For 10 hours, we were surviving rather than racing. It was the worst I’ve seen and something I don’t want to see again. It certainly did change our lives.”

Popular searches

Popular pages.

Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race: 70 Years

One of Australia’s most popular and enduring sporting events is the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. The race starts on Boxing Day and the passage down the east coast grabs national attention over the Christmas and New Year break, giving ocean racing an annual moment in the spotlight. It is internationally recognised as one of the three classic blue-water ocean races, along with the Fastnet Race in the UK and Bermuda Race on the east coast of the USA.

Rolex Sydney to Hobart

The 2014 race will be the 70th in the series. In a sign of the times the race has a contemporary sponsor, Rolex, but the heritage of the race is now strongly recognised by all who have taken part in the past as well as those involved in this year’s event, and it’s a much bigger story than just a three-to-four-day race down the coast.

Ocean racing is just that—racing yachts out on the open sea. It takes place in a natural environment and the crews and yachts have no control over what conditions the sea may provide. There are flat calms through to storm-strength gales, currents and tides, variable wave and swell patterns, and the ever-shifting wind, over day and night—the only constant is change. A race report from the first event describes it well: ‘those two irresponsibles—wind and wave’.

And there are no lanes, signposts or field markings to show the way. The boundaries of the course are the coastline and the landmarks that tick off milestones on the course. These days you can rely on GPS to pinpoint where you are, but in the past precise navigation depended on how accurate you were with sun, moon and star observations. This was a time when your direction and destiny very much relied on human-powered calculations and then, when the weather closed in, your best estimation.

'Ichi Ban' soon after the start of the 2002 Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. © Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

There is no pit lane to pull over into for repairs, changes of personnel and refuelling—once you start, you have to be self-sufficient to the end. You are always working the yacht and can change the configuration while you are sailing—different sail trim and combinations allow the crew to adjust the boat to the conditions, and the winners monitor and optimise the boat constantly to keep it sailing at its full potential. But you’re working with very expensive and sometimes fragile gear and sail changes have to be done with care, especially in challenging conditions.

The backup to gear failure is how you react to incidents on board, making running repairs where possible or having something spare in reserve or a margin of safety that allows you to carry on despite damage.

Navigator Bill Lieberman on Wayfarer in the 1945 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

The safety net as such is waiting off to one side, hopefully not needing to be initiated. Communications, flares, a life raft, EPIRBs, survival suits, even pre-race training and simulations—this is all secondary gear rigorously monitored and enforced, yet marking time until things go seriously wrong. Onshore emergency services are there to respond, but they too have their controls and limits, and self-help among the competing yachts is a code of practice that comes into play to help avoid a catastrophe. The risk of this is always there, and there have been notable times when it has played out in public view.

Teamwork and leadership are intrinsic qualities needed throughout to keep harmony among crew, to maintain their enthusiasm and ability to push on, and to keep it all under control and operating at a high level.

It’s a race full of intriguing contrasts: how the amateurs and Corinthian sailors mix with the professional sportspeople and Olympic representatives in the crews; the high-tech races against those of the previous generation; even down to the historic—how many other sports have such a diverse range of participants and equipment, all sent off at the same time, aiming for the same goal, on the same course? The top boats were all high-tech in their time, but those of today seem even more so—hugely expensive racing machines built with advanced materials to fine tolerances, carrying only what is needed to support the crew so they can operate efficiently, forcing them to live and work around the yacht and its gear.

Participants will experience a huge range of emotions over the journey, and require stamina to see it through. The extraordinary scenery along the way seems a contradiction to the serious racing intent, but the atmosphere can be uplifting and this feeling becomes part of the reason crews return to race in the open sea time after time.

Experience is a factor that helps enormously and only comes with time and determination, but come it does for the many sailors who feel the addiction of this sport and return each year to take on the Hobart race.

The crew of Ilina during the 1960s, with a young Rupert Murdoch third from the left leaning on the boom. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

The history of the race

The Sydney to Hobart race began in an off-the-cuff fashion. In the latter part of World War II, sailors on Sydney Harbour formed the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) to promote cruising and casual races in lieu of those suspended during the previous war years. Their first official event was in October 1944. During 1945 three of the members—Jack Earl, Peter Luke and Bert Walker—planned a cruise to Hobart in their respective yachts after Christmas. One evening Captain John Illingworth RN gave a talk to the club members, and afterwards Peter Luke suggested Illingworth might like to join the cruise. Illingworth’s reply was ‘I will, if you make a race of it’.

And so it was. The Sydney Morning Herald on 16 June 1945 noted that ‘Plans for a race from Sydney to Hobart, early in January 1946 are being made by the Cruising Yacht Club … five possible entries had already been received’.

Later, in the Australian Power Boat and Yachting Monthly of 10 October 1945, there is a more formal notice.

Yacht Race to Tasmania: It is expected that an Ocean Yacht Race may take place from Sydney to Hobart, probably starting on December 26, 1945. Yachtsmen desirous of competing should contact Vice President Mr P Luke … Entries close December 1 1945.

From these small beginnings the cruise became a race and Captain Illingworth helped with the arrangements, showing the club how to measure the boats and handicap the event. The plans, expectations, the probables and possibles of earlier reports—they all turned into reality at the entrance to Sydney Harbour just inside North Head on Boxing Day in 1945, when nine yachts set forth, including Illingworth in his recently purchased yacht Rani . Illingworth had previous experience of ocean racing from his homeland in England and in the USA, where he was a respected competitor, and he prepared Rani to race to Hobart, and not just sail there. The other sailors had a more relaxed attitude.

The crew of Wayfarer in the 1945 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race: (Left to right) Geoff Ruggles, Len Willsford, Brigadier A.G. Mills, Peter Luke (at rear), Bill Lieberman, Fred Harris. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia

That first race encapsulated many features now associated with the event, and in hindsight was a warning of things to come. A strong southerly gale hit the fleet on the first day, and many were unprepared for the rough seas that scattered the fleet. Some boats hove to, one retired and the others sought shelter. Wayfarer ’s crew went ashore twice to phone home before resuming the race, including a stop at Port Arthur. According to Seacraft magazine of March 1946, ‘Licensee of the Hotel Arthur put on a barrel of beer specially for Wayfarer ’s crew, and they enjoyed their first drink of draught beer since they left Sydney on Boxing Day. A local resident treated the ship’s company to a crayfish supper, which was the gastronomic highlight of the voyage’.

Meanwhile the experienced Illingworth, who had prepared Rani and his crew well, had continued to race his yacht throughout. Before the race it was reported that the RAAF would put planes on patrol to keep the yachts under observation, but the weather had made that very difficult. When the gale eased and an aircraft was dispatched to look for the fleet, Rani was so far ahead that it was not located and was presumed missing. The press had the event as their headline article, and later the sudden reappearance of Rani off Tasman Island was a sensation. Rani won easily and the remaining seven boats gradually crossed the line in Hobart, bringing more stories of the race ashore for the public to enjoy.

This impressive coverage for the period ensured the race would continue, and by March 1946 media reports noted that the club secretary, A C Cooper, had said it would be an annual event starting on Boxing Day. As it went ahead in its second year the race included tighter regulations based on those used by the Royal Ocean Racing Club of Britain.

Spectators watching the start of the 2006 Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. © Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

It has been run every year since, and the fortunes of the event have varied. There has been consistent strong public interest, and crowds line the harbour and its foreshores to watch the Boxing Day start, a tradition in parallel with the Melbourne Boxing Day Test match.

Media interest is not confined to the east coast; the race is followed throughout the country and the results are reported internationally. The attention is often on who will finish first, and the focus on this line honours contest has been encouraged to maintain the media interest. Vessels from overseas have raced regularly with the local fleet since the early 1960s, and the race has been won on handicap and line honours by a modest number of craft from outside Australia.

It quickly became recognised as one of the major offshore races, along with the famous Fastnet race in the UK and the Bermuda race starting in the USA, due to the tough and demanding conditions the fleet usually has to overcome. In response to this, the CYCA established good safety precautions quite early on, which for many years it updated in line with the evolution of the participating craft. It often established precautions or limits not enforced in other events. From 1951 onwards there has been a radio relay vessel accompanying the fleet, and safety items carried by the boats and crew remain a priority in the organisation of the race.

Start of the 1986 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Courtesy Cruising Yacht Club of Australia Archives

The 1998 race captured world attention when the most extreme conditions in the race’s history were encountered. A strong southerly-flowing current was mixed with a south-west gale caused by an almost cyclonic depression travelling east across Bass Strait. This had developed soon after the race began and was predicted by many weather forecasters. Winds of more than 80 knots were recorded, but the opposing wind and current directions produced difficult seas with an unusual number of enormous waves which caused the most damage. Yachts were knocked down beyond 90 degrees, and some rolled completely. Numerous yachts were unable to withstand the continuous battering and were forced to heave to or otherwise adopt survival techniques before retiring with damage. A small number were abandoned and later sunk, and six lives were lost off three boats in different circumstances.

The rescue effort was chaotic for a period as there were too many calls to respond to, but the heroic efforts by the civilian and service rescue helicopter crews, filmed by press helicopters working in the same extreme conditions, along with help provided by racing yachts standing by stricken competitors, combined to save many sailors and avoided a total catastrophe.

In the reviews and enquiries that followed a number of factors emerged that had contributed to the disaster. The race organisers then moved quickly to address the deficiencies in the equipment and experience which had been highlighted by the race conditions and the fleet’s inability to cope with them.

The race has had highlights in many areas, in particular the dash for line honours. Perfect conditions with a northeast breeze have helped establish race records. In 1973 the reinforced cement-hulled Helsal —referred to by some as the ‘floating footpath’—caught people by surprise to set a record, but it did not last long. In 1975, the world-beating maxi yacht Kialoa III came across from the USA, and owner Jim Kilroy steered it to a new record, well under three days. The 1999 the water-ballasted Volvo 60 class yacht Nokia was able to take maximum advantage of the strong north-east wind pattern. Nokia set a new race record of 1 day 19 hours and 48 minutes at an average speed of 14.39 knots. This was nine hours faster than Kialoa III ’s longstanding record from 1975, on which Morning Glory had briefly improved by 30 minutes in 1996, 21 years after Kialoa ’s triumph.

A curious line honours winner was Nocturne in 1953, a 10.66-metre (35-foot) long sloop designed by Alan Payne, which mastered unusually light and fickle conditions to beat much larger craft in a slow race with no retirements.

Wild Oats XI about to finish the 2011 Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. Taken from Sandy Bay, Hobart. Wikimedia Commons/JJ Harrison

The record now stands at 1 day, 18 hours and 23 minutes, set by Wild Oats XI in 2012. Wild Oats XI has twice taken line honours, set the record and won on handicap (2005 and 2012). Rule changes since 1999 permitted vessels up to 30.48 metres (100 feet) in length, and with favourable conditions the new super-maxis built to this limit easily had the potential to improve on the record.

When Huey Long from the USA brought his aluminium yacht Ondine in 1962, one of the closest finishes occurred when Ondine narrowly beat the Fife-designed schooner Astor and the steel Solo across the line, but Solo won on handicap.

The handicap winner is the true winner of the race, a fact sometimes obscured to the public as the bigger boats dominate the headlines. A small number of boats have ‘done the double’ and won both, including Wild Oats XI in 2005, which scored a treble with the race record as well. However quite often the trophy has gone to a well-sailed yacht towards the middle of the finishing order, and sometimes the changeable weather patterns favour the smaller yachts towards the tail end. The most notable handicap winner is the Halvorsen brothers’ Freya , which achieved the remarkable feat of winning three races in succession, from 1963 to 1965. Love & War has also won the race three times, in 1974, 1978 and 2006. Screw Loose , at 9.1 metres LOA, won in 1979 and is the smallest yacht to have won the race.

The end of the race is marked with celebrations by all the crews, and the area around Hobart’s Constitution Dock is packed with spectators, crews and their families who have come down to join them. In the same tradition as at the start, the people from Hobart turn out to see the finish, and even when this occurs overnight there is still a strong contingent on and off the water waiting for the gun to go off.

For many yachtspeople the Sydney to Hobart race is the highpoint of their season and their sport. Some aspire to do it just once, while others come back year after year. The challenging conditions might appear to be the primary drawcard in many instances, but the attractions of blue-water sailing have seduced many competitors in the long run. The moods and atmosphere of the wind and ocean, and the satisfaction of sailing a yacht in these elements, are truly felt and understood by the great majority of the crews.

The combination of strong public interest and the enduring attraction of the race for the competitors would seem to ensure that the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race will remain a regular event, and continue to contribute to Australia’s maritime heritage.

The first yacht to finish receives a royal welcome in Hobart for the Rolex Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. © Rolex/Daniel Forster

NEXT CHAPTER

David Payne

David Payne is Curator of Historic Vessels at Australian National Maritime Museum, and through the Australian Register of Historic Vessels he works closely with heritage boat owners throughout Australia researching and advising on their craft and their social connections. David has also been a yacht designer and documented many of the museum’s vessels with extensive drawings. He has had a wide sailing experience, from Lasers and 12-foot skiffs through to long ocean passages. Since 2012 he has been able to work closely with Aboriginal communities on a number of Indigenous canoe building and watercraft projects.

How one man predicted the 1998 Sydney to Hobart disaster

Topic: Sailing

Alan Payne's notes ( ABC News )

Speech notes obtained by 7.30 show how one man predicted the disastrous loss of life which befell the 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht fleet, 17 years before it happened.

This Boxing Day marks the 20th anniversary of that yacht race, in which six yachtsmen lost their lives. It ended with Australia's biggest peacetime search and rescue mission and one of the largest coronial investigations ever held in New South Wales.

'Six people will be lost overboard'

Naval architect Alan Payne. ( Supplied )

On a warm summer's evening in December 1981, some of Sydney's elite yachtsmen gathered for dinner and speeches at the harbourside penthouse of America's Cup challenger, Syd Fischer. The event took place under the auspices of the Ocean Racing Club.

One of the after-dinner speakers was renowned naval architect Alan Payne, who told the yachtsmen he wanted to "put something before you", but "not in public", according to his speech notes.

"Alan was very concerned about yacht construction in the late seventies," yachtsman John "Steamer" Stanley, who was present that evening, told 7.30.

"[Yachtsmen were taking] light construction into the ocean and it was dangerous. Alan got up and started to talk about what can happen in Bass Strait in the worst scenario."

By calculating the number of boats in the Sydney to Hobart race in high 35-knot winds, and the frequency of rogue waves, which can be more than twice the height of other waves, Mr Payne gave the yachtsmen a warning.

One of Alan Payne's handwritten speech notes. ( ABC News )

"You would have to do 1,000 Hobart races to be sure of seeing one [rogue wave]. You needn't [worry], but the administrators must," Mr Payne's speech notes read.

"Three [boats] will completely disappear. There will be numerous capsizes and dismastings and injuries. Six people will be lost overboard."

John Stanley was in the room when Alan Payne gave his speech. ( ABC News )

Mr Payne even spoke of the "grief and hardship those deaths will bring".

"When he finished that speech, no one in that room wanted to go south [to Hobart]," Mr Stanley said.

Seventeen years after Mr Payne's prophetic speech, Mr Stanley was winched by a rescue helicopter out of the Southern Ocean after spending 28 hours adrift on rogue seas, which claimed the lives of six of his fellow yachtsmen.

"He said one day it would happen," Mr Stanley told investigating police at Pambula Hospital, NSW, on December 29, 1998.

"When we were caught in Bass Strait that afternoon, I realised that this is what Alan was talking about."

'Water like darts in your face'

Dismasted yacht Stand Aside tows a liferaft while stranded in the Bass Strait. ( AP: Ian Mainsbridge )

Mike Marshman was aboard Stand Aside in 1998, one of the first yachts to be dismasted by rogue waves and high winds.

"It also blows the water off the sea, off the tops of the waves which, if you look at it, it's like darts hitting your face," Mr Marshman told 7.30.

"Communication is difficult, because the sound of the wind blows your voice away, so you have to yell, scream, almost use sign language to get your message across to the person alongside you."

Mike Marshman was a crew member on Stand Aside. ( ABC News )

The Stand Aside crew's dramatic rescue was captured by an ABC News helicopter.

"The helicopter pilot said at one stage he had 100 feet of clearance and it went to 15 [feet]. So that's an 85-foot wave, if you can imagine it," Mr Marshman said.

"We were lucky, I suppose, the fact that we went over first, so the rescue effort came to us instead of going to Winston Churchill.

"If we had gone second, we may have had a similar circumstance," he said.

Three crewmen from the Winston Churchill — Mike Bannister, Jim Lawler and John Dean — died.

Despite his near-death experience, Mr Marshman maintains that in sailing, there's no reward without risk.

"People who do the Sydney to Hobart, or the Fastnet Race in England or climb Mount Everest, are basically thrill-seekers or they just love sailing, so if you put too many rules into it, you'll take the thrill and the thrill-seeking part of it away," he said.

It was an attitude which was slammed by the investigating NSW coroner in the inquest held two years after the race.

'Sailors had a cavalier attitude'

Former coroner John Abernethy was surprised to find some sailors had little knowledge of the concept of rogue waves. ( ABC News )

For retired investigating NSW coroner, John Abernethy, it was one of "the biggest inquests I have ever done and one of the biggest inquests that have been held in this state".

"Based on the evidence I heard from crew and skippers, it was one of largely experienced sailors and masters, some who had a cavalier attitude — it's a man's sport and it should stay that way," Mr Abernethy told 7.30.

"I found it curious that they had quite a poor knowledge of the theory of weather. For example, in general terms the experienced sailors who came before me in my witness box had quite a poor knowledge of the concept of rogue waves," he said.

'That's not how he wanted to go'

Jim Lawler died in the 1998 Sydney to Hobart. ( Supplied )

Jim Lawler died after being washed away from the life raft he clung to with fellow Winston Churchill crewman John Stanley.

His son, John Lawler, is still upset when people say his father "died doing what he loved".

"That's not how he wanted to go," Mr Lawler told 7.30.

"It would've been terrifying to be cold, wet, dark, unable to breathe."

Mr Lawler said that race revealed the self-interest in the ocean-sailing community.

"We were quite surprised at some of the people that really wanted us to keep quiet about things, not raise any questions about it, not make any fuss, which we couldn't quite understand," he said.

"They were all worried about how this was going to make insurance premiums go up for next year's race.

"To be perfectly frank, it made me stop sailing. I'm not that interested in participating in the clubs that organise these races.

"I'm still sort of unsure why they acted in the way they did to one of their brothers and the family of their brothers. It took away my passion for it."

- Australia & South Pacific

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -40% $8.94 $ 8 . 94 FREE delivery Friday, September 6 Ships from: SharehouseGoods Sold by: SharehouseGoods

Save with used - good .savingpriceoverride { color:#cc0c39important; font-weight: 300important; } .reinventmobileheaderprice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerdisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventpricesavingspercentagemargin, #apex_offerdisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventpricepricetopaymargin { margin-right: 4px; } $7.21 $ 7 . 21 free delivery monday, september 9 on orders shipped by amazon over $35 ships from: amazon sold by: benjamins bookshelf, return this item for free.

We offer easy, convenient returns with at least one free return option: no shipping charges. All returns must comply with our returns policy.

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Fatal Storm: The Inside Story of the Tragic Sydney-Hobart Race Paperback – May 17, 2000

Purchase options and add-ons.

"Harrowing shoreside reading." Booklist

"Should be required reading for all ocean sailors." Library Journal

The first book to recount the disastrous events of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht race, Fatal Storm is sure to be a popular paperback selection. Rob Mundle takes readers through every white-knuckling hour of the gale that descended in the predawn hours of December 27, stretching over 900 miles from Australia to New Zealand, bringing with it hurricane strength winds and five-story waves. In all, 57 sailors were rescued, plucked from the decks of broken boats or from the sea itself under impossible conditions. Six sailors died.

A Sydney-Hobart Race veteran himself, Rob Mundle had total and unequaled access to the people behind the story. The result is a tale of extreme adventure, extraordinary will, and the overwhelming emotional tales of survivors, rescuers, and the bereaved.

- Print length 272 pages

- Language English

- Publisher International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press

- Publication date May 17, 2000

- Dimensions 5.4 x 0.84 x 7.9 inches

- ISBN-10 0071361405

- ISBN-13 978-0071361408

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who bought this item also bought

Editorial Reviews

From the back cover.

"The famous killer Sydney - Hobart Race has found its chronicler in Rob Mundle. An Australian journalist who was on the scene . . . Mundle's portrayals of courageous sailors and heroic rescuers fighting for their lives are as vivid as any I have read." --John Rousmaniere, author, Fastnet: Force 10

About the Author

Product details.

- Publisher : International Marine/Ragged Mountain Press; 1st edition (May 17, 2000)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 272 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0071361405

- ISBN-13 : 978-0071361408

- Item Weight : 12 ounces

- Dimensions : 5.4 x 0.84 x 7.9 inches

- #9 in Sydney Travel Guides

- #139 in Ecotourism Travel Guides

- #949 in Environmentalism

About the author

Robert mundle.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 75% 14% 7% 3% 0% 75%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 75% 14% 7% 3% 0% 14%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 75% 14% 7% 3% 0% 7%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 75% 14% 7% 3% 0% 3%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 75% 14% 7% 3% 0% 0%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Registry & Gift List

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The 1996 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, sponsored by Telstra, was the 52nd annual running of the "blue water classic" Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race. As in past editions of the race, it was hosted by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia based in Sydney, New South Wales. As with previous Sydney to Hobart Yacht Races, the 1996 edition began on Sydney ...

In December of 1998, a fleet of sailing yachts made record pace on the first leg of the prestigious Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, before being met by a superc...

The 1998 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race was the 54th annual running of the "blue water classic" Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race.It was hosted by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia based in Sydney, New South Wales.It was the most disastrous in the race's history, with the loss of six lives and five yachts. [1] 55 sailors were rescued in the largest peacetime search and rescue effort ever seen in ...

The Rolex Sydney Hobart Yacht Race is an annual event hosted by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, ... crewed on One Time Sidewinder 1996; In 1994 at the 50th Sydney to Hobart, Albert Lee was a part of the making waves foundation's team which was the first time a fully disabled crew had sailed in an ocean race. [47] Worst disaster: 1998, 6 ...

The start of the race, Boxing Day 1998. Simon Alekna. A fateful decision by five shipwrecked Sydney-Hobart yachtsmen to cut an air hole in the floor of their overturned life raft ended in three of ...

To mark the 20th anniversary of the deadly 1998 Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, Four Corners unearthed this archive episode investigating what happened in that ...

Boxing Day dawned hot but clear over the mainland harbour city for the start of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart race. The nor'east sea breeze was building and most sailors on the 115 competing yachts ...

The 1998 Sydney to Hobart ended in disaster. On the Business Post Naiad yacht, two crew died. ... Ms Golding said that we could "absolutely" see a storm like 1998 affect the Sydney to Hobart yacht ...

Davidson is talking about the crew of the Stand Aside, one of the stricken yachts in the 1998 Sydney to Hobart ocean race. The 1998 Sydney to Hobart turned to tragedy when it was struck by a ...

70 Injured. $5 million Insurance Costs. Shortly after the commencement of the annual Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, a 'super cell' storm stirred up massive seas in the Bass Strait. The storm cut through the fleet, resulting in the drowning of six sailors (from New South Wales, Tasmania and Britain). Seven yachts were abandoned at sea and lost.

Pretty much most of the crews in the Sydney Hobart are people racing pretty much continuously.". The emphasis on safety has increased costs. "It probably costs about 60,000 Australian dollars ...

In 1998, David Key of the Victorian Police's air wing became the designated Tea Bag aboard a rescue helicopter roaring towards Bass Strait and an unfolding disaster in the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race.

It was day two of the 1998 Sydney-to-Hobart yacht race and it was a bloody ugly one. Mountainous seas and scathing winds lashed the 43-foot yacht Sword of Orion as she headed into Bass Strait ...

Out of the tragedy came an inquest which saw a Cruising Yacht Club of Australia (CYCA) race director resign, and the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM) increase the depth of its forecasting. It has ...

The 115-yacht fleet sailed into the worst weather in the Sydney to Hobart's history. Six sailors died and just 44 yachts survived the gale-force winds and mountainous seas to finish the race. Two crew members died on the Launceston yacht Business Post Naiad, one by drowning, the other from a heart attack at the height of the storm.

Yacht Race to Tasmania: It is expected that an Ocean Yacht Race may take place from Sydney to Hobart, probably starting on December 26, 1945. Yachtsmen desirous of competing should contact Vice President Mr P Luke …. Entries close December 1 1945. From these small beginnings the cruise became a race and Captain Illingworth helped with the ...

In 1998 six lives were lost and more than 50 sailors had to be rescued from rough seas during that year's Sydney to Hobart yacht race. It was the biggest disaster in the Sydney to Hobart's long ...

About Press Copyright Contact us Creators Advertise Developers Terms Privacy Policy & Safety How YouTube works Test new features NFL Sunday Ticket Press Copyright ...

Speech notes obtained by 7.30 show how one man predicted the disastrous loss of life which befell the 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht fleet, 17 years before it happened. This Boxing Day marks the 20th ...

"Harrowing shoreside reading." Booklist "Should be required reading for all ocean sailors." Library Journal The first book to recount the disastrous events of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart yacht race, Fatal Storm is sure to be a popular paperback selection. Rob Mundle takes readers through every white-knuckling hour of the gale that descended in the predawn hours of December 27, stretching ...

Go to https://www.expressvpn.com/waterline to get an extra three months of ExpressVPN absolutely FREE!Join Patreon https://www.patreon.com/WaterlineStories00...

(28 Dec 1998) English/NatTwo sailors are dead and six others are missing after gale-force winds and high seas battered yachts in the Sydney-to-Hobart race.Th...